USA. 2007.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Quentin Tarantino, Producers – Elizabeth Avellan, Robert Rodriguez, Erica Steinberg & Quentin Tarantino, Photography (colour + some scenes b&w) – Quentin Tarantino, Visual Effects – The Orphanage Inc (Supervisor – Ryan Tudhope), Special Effects Supervisor – Andy Schoenberg, Makeup Effects – K.N.B. EFX Group Inc (Supervisors – Howard Berger & Greg Nicotero), Production Design – Steve Joyner. Production Company – Troublemaker Studios.

Cast

Kurt Russell (Stuntman Mike McKay), Zoe Bell (Herself), Vanessa Ferlito (Arlene), Tracie Thoms (Kim), Rosario Dawson (Abernathy), Sydney Poitier (Jungle Julia Lucai), Rose McGowan (Pam), Mary Elizabeth Winstead (Lee), Jordan Ladd (Shanna), Quentin Tarantino (Warren), Marcy Harriell (Marcy), Eli Roth (Dov), Omar Doom (Nate), Michael Parks (Earl McGraw), James Parks (Edgar McGraw), Jonathan Loughran (Jasper), Monica Staggs (Lanna Frank), Marley Shelton (Dr Dakota Block), Nicky Katt (Counter Guy)

Plot

Jungle Julia Lacai, a popular radio host in Austin, Texas, heads up to a lake for the weekend with two girlfriends. Along the way, they stop at a bar where one of the patrons is a middle-aged man who introduces himself as Stuntman Mike and claims to be a film industry stuntman. At closing, Stuntman Mike offers one girl Pam a ride home in his car, which has been built as a ‘death-proof’ stunt vehicle with roll bars and stunt cages. On the road, he instead turns the car and rams head-on into Julia and friends. They are killed but Stuntman Mike survives. Fourteen months later, New Zealand stuntwoman Zoe Bell arrives off a plane in Lebanon, Tennessee and joins three film industry girlfriends. Zoe wants to fulfill a fantasy of driving a 1970 Dodge Challenger. She has found someone who is advertising one for sale and goes with the others to convince him to let her to take it for a test drive on the pretext of buying it. However, Zoe’s real intention is to play Ship’s Mast where she rides on the hood of the car hanging from two leather belts. As they set out, Stuntman Mike is waiting in his car and determined to ram them off the road.

Quentin Tarantino emerged onto the cinematic stage in the mid-1990s as writer-director with the double slam of Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994). These are two films that tower with a polished cool and an extraordinary confidence of storytelling. Tarantino has a love of the sound of dialogue for its own sake – he manages to elevate nonchalant chatter about nothing to an artform. His films come with wry margin notes that show a love of cinema, especially 1970s exploitation cinema. Tarantino also managed to craft iconic roles for several emerging actors (Samuel L. Jackson, Tim Roth, Michael Madsen, Steve Buscemi) and in particular brought back out of mothballs several actors whose star had started to fade and gave them roles that caused audiences to respect them anew (John Travolta, Pam Grier, David Carrdine). As is evident in Death Proof, Tarantino also chooses soundtracks that do amazing things with old songs. The buzz that surrounded Tarantino’s name after Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction was astonishing. In the space of two films, Tarantino becomes the coolest thing on the 1990s Hollywood landscape, while his films inspired an ultra-violent gangster chic that saw numerous imitators.

Two films like these are a hard act to follow and subsequently Tarantino has trod a never less than watchable line between hit and miss. Other films adapted from old Tarantino scripts like True Romance (1993) and Natural Born Killers (1994) enjoyed reasonable success; his portmanteau film Four Rooms (1995) flopped badly; From Dusk Till Dawn (1996), which he wrote and starred in and allowed good friend Robert Rodriguez to direct, was a reasonable hit; although his Elmore Leonard adaptation Jackie Brown (1997) was a lot quieter and more subdued than people expected it to be. Tarantino then vanished off the Hollywood stage for six years, before returning with Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003) and Kill Bill Vol. 2 (2004), an enjoyably violent homage to samurai cinema directed and written with the brashly assured Tarantino cool, and then the overrated World War II film Inglourious Basterds (2009) and the triumphant Django Unchained (2012), The Hateful Eight (2015) and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019), which brought him back many of the accolades that Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction had enjoyed.

It has always been of some surprise that Quentin Tarantino had never ventured into genre cinema before as his love of 1970s exploitation cannot help but cross over into a considerable body of genre material. Certainly, Tarantino has peripherally touched upon the genre a number of times. The most notable example was From Dusk Till Dawn, as well as his script that eventually ended up as Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers. Tarantino’s sometimes production company A Band Apart did produce two interesting genre works with the race-reversed alternate world film White Man’s Burden (1995) and the black comedy Curdled (1996) about a meeting between a forensic cleaner and a serial killer. Tarantino has also acted as executive producer for Eli Roth’s torture fest Hostel (2005) and purportedly did uncredited script rewrites on Crimson Tide (1995).

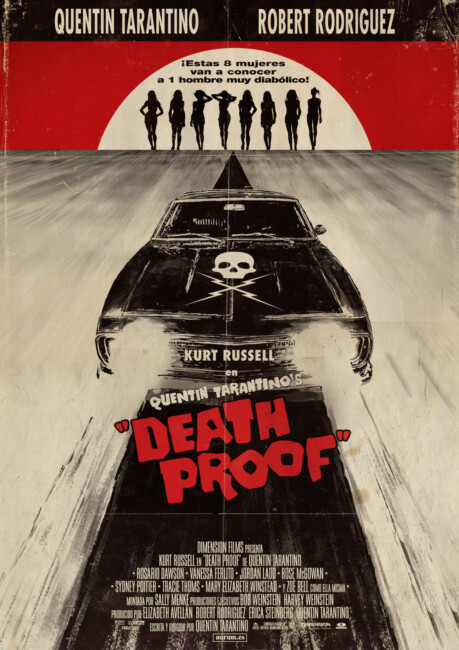

And then there was Grindhouse (2007). Tarantino and best friend director Robert Rodriguez had done a great deal of work on either’s films – Tarantino plays a minor role in Rodriguez’s Desperado (1995); the two had combined forces on From Dusk Till Dawn; Rodriguez directed a single scene in Pulp Fiction, while Tarantino is credited as a ‘guest director’ on Rodriguez’s Sin City (2005). The idea of Grindhouse, which was produced under the banner of Rodriguez’s Troublemaker Studios, was of a double-bill designed as a homage to 1970s exploitation cinema (the title referring to theatres that kept playing luridly exploitative material round the clock). Tarantino and Rodriguez each directed one complete film of 85 minutes apiece – Tarantino with Death Proof and Rodriguez with the zombie film Planet Terror – and it was released as one entity. To add to the mix, various other director friends – Eli Roth, Rob Zombie and Edgar Wright of Shaun of the Dead (2004) fame – directed several faux coming attractions trailers. Two of these were later expanded into full-length films Robert Rodriguez’s Machete (2010) and the Canadian Hobo With a Shotgun (2011).

But then the unthinkable happened. Grindhouse opened in the US in April 2007 and, despite rave reviews and an enormous amount of excited advance buzz by media press, it flopped, earning a well-below-expected (although not entirely immodest) $11.5 million on its opening weekend. A variety of reasons have been put down to explain this failure, the most predominant being that American audiences, many being of the younger generation who had never seen a double-bill, were not aware that Grindhouse was two films and walked out after the end credits for the first film came up. Faced with a financial flop, distributors Bob and Harvey Weinstein took the same step that they did with Tarantino’s Kill Bill, which was originally one 248 minute film, and cut Grindhouse in two. Tarantino’s half, Death Proof, premiered in a longer cut at the Cannes Film Festival and was then released as its own film in territories outside of the USA. (Rodriguez’s superior half Planet Terror (2007) was sporadically release in the same manner but failed to enjoy the same profile).

The cinematic release of Death Proof differs in a number of ways from the Grindhouse version. The Grindhouse version of Death Proof runs 87 minutes long – Tarantino describes how he edited this version “down to the bone” as much as he could to see if it still made sense. Some 27 minutes footage has been restored to the international version to bump it up to a 114 minute running time. From what one is able to glean (at least without having a copy of Grindhouse to make comparison to), the new material added includes:- the scene where Vanessa Ferlito gives Kurt Russell a lap dance at the bar (which was listed as a missing reel in Grindhouse); a scene with her and Omar Doom outside the bar negotiating to make out but not have sex; extended scenes of the girls talking among one another during the car journeys; the opening scenes of the second half where the girls go into a convenience store and buy a fashion magazine, which is followed by a black-and-white scene where Kurt Russell sneaks up and teases and then tongues Tracie Thoms’ feet as they poke out the car window.

All of that said, Death Proof, even in its extended form, serves only as minor Quentin Tarantino. One of the things that amazed people with both Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction was Tarantino’s extraordinary adeptness at being able to juggle back and forward between linear and overlapping narrative. The same was present with Kill Bill but ended up being lost when the Weinsteins split the film in two. One suspects that sometimes Tarantino is too clever for his own good. He made a big thing out of how From Dusk Till Dawn started as a getaway thriller and then in its latter half pulled audiences feet from under them and turned into something completely different – but instead the abrupt change ended up confusing most. Ditto with Grindhouse where he came up with the missing reels concept, which only ended up being read as annoyingly missing plot elements by audiences.

The main problem with Death Proof is that it has no plot. It feels more like half an idea than a fully developed script. The entirety of the film consists of two near-identical acts where not one but two separate groups of girls who talk tough and ironic, call each other ‘bitch’ and ‘nigger’ a good deal and quote a heap of 1970s exploitation films, go out partying and then come across Stuntman Mike. The long opening preamble with Sydney Poitier, Vanessa Ferlito and Jordan Ladd setting out, visiting not one but two bars and talking about guys, having (or not having) sex, scoring drugs and on-air challenges goes on for some time, certainly much longer than would be permissible in any other kind of commercial release. After the build-up, this half comes to an abrupt ending where Tarantino suddenly pulls our feet out from under us and kills the girls off. This leaves one wondering where the film is going to go next. We then come to the second part where we get another carful of girls who then set out driving, talking tough and ironic, discussing guys and sex etc. It feels like Tarantino is so in love with his own dialogue that that he has started repeating himself. Particularly during the scenes set in the cafe, Tarantino’s hiply nonchalant dialogue has started to seem flabby and one wishes the film would just get on with it and go somewhere.

You can clearly see that Quentin Tarantino has focused only on the things that interest him – the girl’s sharp and acerbic dialogue, paying reference/homage to 1970s car chase movies and setting up things for the long extended stunt chase that climaxes the film. However, what we end up with is an unbalanced film that panders to Quentin Tarantino’s interests more than feels a satisfying film. The idea may have worked as a half-hour episode of some anthology series but has been extruded out to become nearly a two-hour film. Much of the plot seems overlooked or neglected. Who Stuntman Mike is remains unexplained. In terms of a psycho film, there are only the most minimal aspects there, certainly not enough for Death Proof to feel satisfying as a story.

Being a Quentin Tarantino film, Death Proof naturally comes packed with cinematic quotes. When we visit the convenience store at the start of the second half, a pan along a magazine rack shows it stacked with copies of magazines like Fangoria, Psychotronic Cinema and Shock Cinema. Both the apartment and bars, even people’s T-shirts, are covered with classic movie posters. Kurt Russell has a speech about how he did stunt work on shows like The Virginian (1962-71), The High Chaparral (1967-71), Vega$ (1978-81) and Gavilan (1982-3) and reacts with what suspects is some disappointment on Quentin Tarantino’s part that none of the girls remember any of these. Tarantino makes a good deal of mention of 1970s car chase movies – the cult classic Vanishing Point (1971) is referenced a number of times, along with other car chase films like Crazy Mary, Dirty Larry (1974) and Gone in 60 Seconds (1974), with effort made to point out what is meant in regard to the latter is “not the version with Angelina Jolie”. Throwaway quips are made comparing things to Cannonball Run (1981), Stroker Ace (1983) and B.J. and the Bear (1979-81). Kurt Russell has a speech that laments the replacement of good old-fashioned stuntwork with CGI – and when it comes to the climactic car chase sequence, Tarantino gives us a good old-fashioned foot-to-the-pedal chase where we can see that it is clearly a real stunt person rather than anything digital.

The cast are variable. Kurt Russell is serviceable. Tarantino has clearly done what he did with John Travolta, Pam Grier and David Carradine and attempted to give a career revival to another 70s/80s icon. (The original casting choice for the part of Stuntman Mike was Mickey Rourke who gained a major career revival in Rodriguez’s Sin City and would have sizzled playing the part one suspects. Alas, Rourke departed after creative differences with Tarantino). Maybe one day it will get through to Tarantino that he is not an actor – he has a cameo here as a bartender and manages to seem even more annoying and geeky than ever.

Rosario Dawson and Rose McGowan, being the most well known actresses among the cast, are surprisingly left in the background and their respective segments dominated by lesser known actresses – Vanessa Ferlito, Zoe Bell, Tracie Thoms. The entire show is fairly much owned by Vanessa Ferlito, previously a regular on CSI: New York (2004-13), who must surely have the sexiest pair of lips in Hollywood, and steals the entire film with her lap dance scene, which is a genuine show capper and the point where Death Proof suddenly gains life. Tracie Thoms also makes a strong showing in the second half. Although surprisingly, for having homaged 1970s exploitation cinema so explicitly and for a film featuring such a large all-girl line-up, Tarantino never does what any true exploitation producer/director of the 1970s would have done and gets a single one of them undressed.

One of the surprise pieces of casting is New Zealand born stuntwoman Zoe Bell, who had previously worked for Tarantino as Uma Thurman’s stunt double in Kill Bill. Although the film makes Bell into the lead character during the second part, she is not much of an actress. She appears nervous and delivers most of her performance through a series of blinks and awkward facial scrunches – sort of if you might imagine a Drew Barrymore suffering from cerebral palsy. The reason for Zoe Bell’s presence is apparent when Tarantino gets to the car chase scenes that climax the film, where it is clearly her on the hood of the car and no double. (It was highly amusing watching Death Proof in a cinema in New Zealand as there was a huge cheer that went up when it is mentioned how people will get their asses kicked for mistaking New Zealanders for Australians. Although Tarantino is slightly out in claiming that Auckland has an outdoor theatre as no such thing exists in the entire country, apart from occasional novelty events).

(Nominee for Best Supporting Actress (Vanessa Ferlito) at this site’s Best of 2007 Awards).

Trailer here