Crew

Director – Eugene Lourie, Screenplay – Thelma Schnee, Story – Willis Goldbeck, Producer – William Alland, Photography (b&w) – John F. Warren, Music – Van Cleave, Photographic Effects – John P. Fulton, Process Photography – Farciot Edouart, Makeup Supervisor – Wally Westmore, Art Direction – John Goodman & Hal Pereira. Production Company – Paramount/William Alland Productions.

Cast

Otto Kruger (Dr William Spensser), John Baragrey (Dr Henry Spensser), Mala Powers (Anne Spensser), Charles Herbert (Billy Spensser), Robert Hutton (Dr John Carrington), Ross Martin (Dr Jeremy Spensser)

Plot

Dr Jeremy Spensser is declared a genius for his work with cultivating crops that can solve world hunger problems. Returning from accepting a peace award in Stockholm, Jeremy runs to catch his son Billy’s toy plane after it is blown away only to be hit and killed by a truck. His father, the neurologist William Spensser, is distraught and locks himself away in his laboratory, spending all his time working on a secret project. Sometime later, he reveals to Jeremy’s brother Henry that he has successfully preserved Jeremy’s brain inside a tank. He asks Henry’s mechanical expertise in building a robot body to house the brain. They construct a hulking colossus. After the brain is placed inside it, Jeremy slowly, hesitantly comes to life in the mechanical body. He then sets about to complete his research. After going to visit his graveside, he meets Billy again. However, at seeing his wife with Henry, he feels rage and starts to become uncontrollable.

Director Eugene Lourie is a name of some genre interest. Starting out as an art director and production designer, first in his native France and then moving to the US, Lourie only took the director’s chair on four occasions but each of these was a genre film. The first was The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), the Ray Harryhausen stop-motion animation vehicle about an atomically revived dinosaur amok in New York City. This was one of the 2-3 most influential films of the 1950s in that it was the very first atomic monster film. Lourie next made The Colossus of New York. He was evidently in demand as a monster movie maker and was brought to England to make one further stop-motion animated atomically revived dinosaur film with The Giant Behemoth/Behemoth the Sea Monster (1958), which was intended as a copy of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and is a weaker effort, and the far superior non-atomically revived, non-stop motion animated dinosaur film Gorgo (1961). Lourie returned to art direction in subsequent years up until his death in 1991.

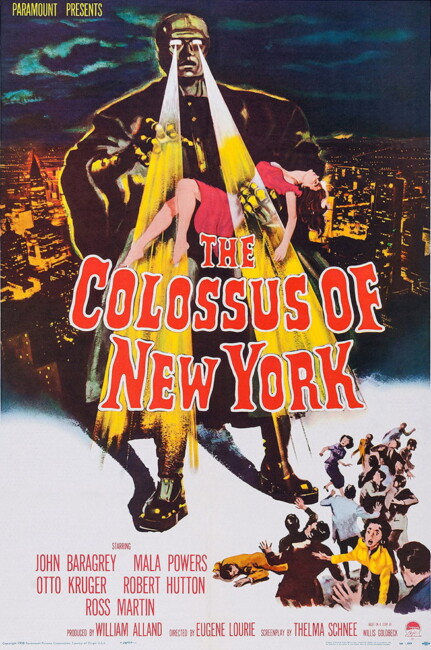

The Colossus of New York is a Frankenstein film. That and a few dashes of the classic disembodied brain story Donovan’s Brain (1943), filmed as The Lady and the Monster (1944), Donovan’s Brain (1953) and The Brain/Vengeance (1962). More so, it is a Frankenstein film reworked for the 1950s era of the Space Age and in particular the Age of the Computer than began around the same time with the advent of Univac. Apart from a handful of stragglers, most notably The Fly (1958), the mad scientist film that was thriving in the 1940s died away in the 1950s and the scientist was regarded as a hero rather than a threat to society. Certainly, The Colossus echoes with imagery from classic monsters – its large, hulking nature and especially the climactic scene where the child pulls the switch that deactivates it reminds a good deal of The Golem (1920); the pathos of the scenes with it empathising with the boy resonate with memories of the Boris Karloff Frankenstein (1931). The Colossus even engages in the good old monster movie standby of carrying a woman off in its arms – although this has an added poignancy in that the woman is the wife of the man inside the robot’s body.

On a plot description level, The Colossus of New York is unexceptional but Eugene Lourie makes something extraordinary out of it directorially. The Colossus is an unearthly creation – large (something like nine feet tall), ungainly, frequently shown sinisterly underlit and speaking with an alienated electronic voice and looking wonderfully sinister stomping about with its eyes lit up. There is a fascinating scene with Otto Kruger and John Baragrey bringing the Colossus to life and it slowly starting to awkwardly clomp about while trying to modulate its voicebox in order to speak.

There are some wonderfully creepy scenes – like where a paranoid John Baragrey calls Otto Kruger on the phone “He can see me,” and suddenly there comes the mechanical voice from behind Kruger “Yes I can” and the robot’s eyes light up in the dark and it eerily advances into camera, telling where Baragrey is right down to the cross street. In the next scene, we see it emerge from the river to obliterate Baragrey with lightning bolts from out of its eyes. There is a fabulous climactic scene where the Colossus appears at the United Nations, standing in stark relief against the Swords Into Ploughshares mural blasting the crowds below with its eye raybeams, before his young son Charles Herbert runs up to it and it begs him to pull the lever and end its suffering.

There is a certain theme that runs through much of 1950s science-fiction – of the divorce between the mind and emotions, that the intellect on its own untempered by feelings is something dangerous. You can see this in films like Forbidden Planet (1956) and at its most absurd with the hopping brain invasion of Fiend Without a Face (1958). Here Otto Kruger announces his experiments whereupon Robert Hutton is given to comment in horror: “The brain divorced from human experience will become dehumanised to the point of monstrousness,” to which Kruger’s response is “You are an idiot. An idiot.” At the end, Kruger is given to reflect on the error of his ways: “You’re right Carrington – without a soul, there’s nothing but monstrousness.” Notedly in contrast for the scientists of the 1930s and 40s, Otto Kruger ends the film simply shrugging and admitting he was wrong whereas a decade earlier he would be made to pay for his hubris and probably go out destroyed by his own creation.

There is still the other odd line that makes you do a double take today, like when John Baragrey is insistent on giving young Charles Herbert the rather creepy greeting (in reference to the coat he is wearing): “Billy, you want to look in my pockets and see what I find for you.”