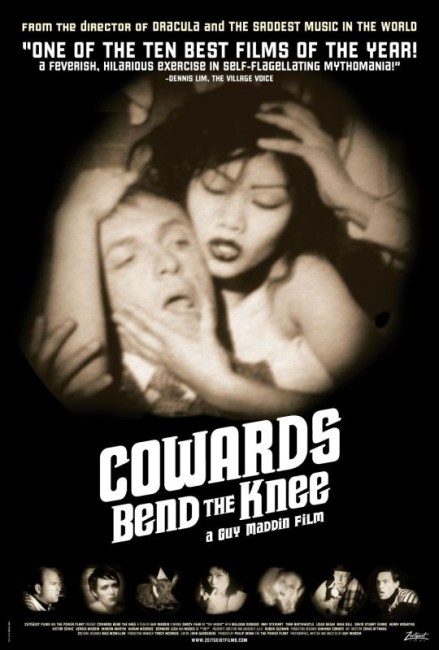

Canada. 2003.

Crew

Director/Screenplay/Photography (b&w + tinted) – Guy Maddin, Producer – Philip Monk, Production Design – Shawna Conner. Production Company – The Manitoba Film Commission.

Cast

Darcy Fehr (Guy Maddin), Melissa Dionisio (Meta), Amy Stewart (Veronica), Louis Negin (Dr Fusi), Tara Birtwhistle (Liliom), David Stuart Evans (Shaky), Herdis Maddin (Grandma), Mike Bell (Mo Mott), Henry Mogatas (Chas), Victor Cowie (Maddin Sr)

Plot

Guy Maddin is a player with the Winnipeg Maroons ice hockey team. After a bump on the head during a game, Guy loses his memory. Not knowing what he is doing, he is seduced away from his girlfriend Veronica by Meta, the daughter of the hairdresser Liliom. However, Meta will not let Guy put his hands on her until her father’s death is avenged. Meta saw Liliom and her lover Shaky, the police captain, strangle her father Chas during a shampoo. Meta has had her father’s hands severed. She now has Guy chloroformed and then orders Fusi, the team doctor, to transplant her father’s hands onto Guy’s wrists. Fusi thinks the request crazy and instead throws the hands away and paints Guy’s hands blue to fool her. Thinking he has Chas’s hands, Guy goes on a killing spree.

Canada’s Guy Maddin is one of the most unique and distinctive directors in the world. Maddin first appeared with Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1989) and went onto increasingly more well-known arthouse films such as Archangel (1990), Careful (1992), Twilight of the Ice Nymphs (1997), Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary (2002), The Saddest Music in the World (2003), Brand Upon the Brain! (2006), My Winnipeg (2007), Keyhole (2011), The Forbidden Room (2015) and The Green Fog (2017). All of Guy Maddin’s films seem like artifacts from a silent movie era that never was, where Maddin is constantly recreating the lighting and camerawork of the period and has a great fascination with German Expressionist sets. At the same time, Maddin’s films come overrun with a surreal banality, of hysterically melodramatic plots and characters uttering purple prose dialogue in perfect deadpan.

Cowards Bend the Knee began not even as a film but as an art installation commissioned by The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto. Cowards Bend the Knee is only 60 minutes long and Maddin originally conceived it so that it could be viewed in 10 separate segments of 6 minutes each where gallery visitors would step up to a peephole and watch each episode playing. The film was repackaged as a single continuous feature for international film festival audiences.

Cowards Bend the Knee came out the same year as Guy Maddin’s more high profile The Saddest Music in the World. Cowards Bend the Knee was made with a miniscule budget – Maddin shot it in five days, on Super 8 (a tradition that has become even more obscure that silent cinema has these days), with no accompanying soundtrack and no recognisable name stars. Saddest Music ended disappointing somewhat and the much more low-budgeted Cowards Bend the Knee is, at least in this author’s opinion, a superior film.

Cowards Bend the Knee trips through most of the main plot elements of Saddest Music – and themes that recur with great regularity throughout Guy Maddin’s work – incest, love triangles, bizarre forms of mutilation, amnesia. (Rather alarmingly, Maddin claims that Cowards Bends the Knee is an autobiographical work about his own disturbed childhood, with the lead character even being named Guy Maddin – which probably explains the recurrence of such themes in his work. In reality, Maddin’s father was a coach for an ice hockey team and his mother ran a beauty salon). While Saddest Music passed through most of the same themes, it seemed a distant reworking of Maddin-esque preoccupations. By contrast, Cowards Bends the Knee wields a similar plot but does so with a directorial élan that often dazzles.

While most of Guy Maddin’s previous movies have sourced the visual style of silent movies, Maddin has set out to make Cowards Bend the Knee as an actual silent movie – there is no dialogue, only intertitle cards (although the soundtrack is filled with various classic music excerpts and occasional sound effects). Maddin employs all the lighting stylistics of silent cinema – the iris camera lens, the exaggerated makeup effects, even touching up the print to give it the worn look of a silent movie being projected today.

At the same time, Maddin has also employed modern cinematic styles – the blurred, undercranked video-shot look favoured of MTV directors, as well as the idea of having the action move as a series of sequential stills that was memorably used by Chris Marker in La Jetee (1962). The photography is also gauzed out in the way that Maddin likes and frequently underlit with quite beautiful results. Even though he is making a silent movie, Maddin’s blending of styles highlights every contorted expression with striking and potent emphasis.

Cowards Bend the Knee is the closest that Guy Maddin has come to making a normal film to date. It is almost something that you could imagine taking places in the melodramatic plottings of a soap opera or a horror movie. Indeed, one of the inspirations for the film appear to have been yet another silent movie – the classic German film The Hands of Orlac (1924), which was remade a number of times, most memorably as Mad Love (1935), about a pianist fooled into believing that he had been grafted the hands of a killer that were taking on a life of their own. The melodrama of the original story is clearly one that has attracted Guy Maddin and Cowards Bend the Knee could almost function as a loose remake.

(Nominee for Best Cinematography at this site’s Best of 2003 Awards).

Trailer here