USA/Japan/France. 1995.

Crew

Director – Christophe Gans, Screenplay – Thierry Cazals & Christophe Gans, Based on the Manga by Ryoichi Ikegami & Kazuo Koike, Producers – Samuel Hadida & Brian Yuzna, Photography – Thomas Burstyn, Music – Patrick O’Hearn, Makeup Effects – Christopher Nelson, Production Design – Douglas Higgins & Alex McDowell. Production Company – Samuel Hadida/Toei Video Co/Fuji Television/Tohokushinsha Film Corp/Davis Films/Ozla Pictures/Yuzna Films

Cast

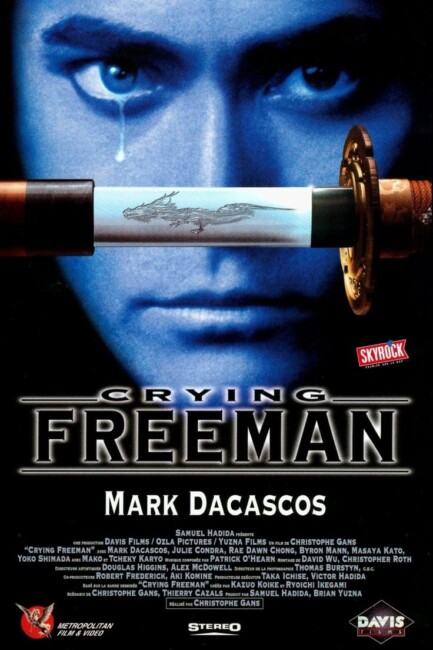

Mark Dacascos (Yo Hinomura/Freeman), Julie Condra (Emu O’Hara), Tcheky Karyo (Detective Netah), Byron Mann (Koh), Yoko Shimada (Lady Hanada), Masaya Kato (Ryuji Hanada), Rae Dawn Chong (Detective Forge), Mako (Shido Shimazaki)

Plot

Artist Emu O’Hara is on holiday in San Francisco when a mysterious man interrupts her idyll as he pursues and shoots two other men. The man saves Emu from falling over a cliff and then vanishes, not before telling her that his name is Yo. Back home in Vancouver, Interpol warns Emu that Yo is the famous Crying Freeman, an assassin for the shadowy organisation known as the Sons of the Dragon, and that she is marked for death because she has seen his face. Freeman returns, but instead of killing her, the two become lovers. He tells her how he used to be the potter Yo Hinomura. After witnessing an assassination, he was taken and brainwashed by a witch to become an assassin for the Sons of the Dragon. Freeman has also become caught in the midst of a war as the Hanada Clan seek to move in on the Sons’ territory. As the Hanada Clan pursue him, Freeman is forced to flee between Vancouver and Hokkaido with Emu in his protection.

Japanese anime and manga attained considerable international attention in the West in the 1990s after the success of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira (1988). Previously much of this material had only existed as a niche department of comic-book stores. It was perhaps inevitable after anime’s breaking through that we started to see Westernised remakes of various anime films and series. One dreaded what would emerge – that the violent and fetishistic drive behind most anime would be subsumed into the standard B-budget action movie. There was the ill-considered adaptations of The Guyver (1991) and Fist of the North Star (1995), which was produced around the same time as Crying Freeman, while various other films were touted but never emerged, at least up until the 00s that saw the live-action adaptations of Speed Racer (2008), Dragonball Evolution (2009), Kite (2014), Ghost in the Shell (2017) and Cowboy Bebop (2021), all of which flopped.

The original Crying Freeman was a manga that ran in Weekly Big Spirit Comics between 1986 and 1988. The plotline concerned a Japanese potter who was recruited and brainwashed as an assassin by a Chinese organisation, his love affair with the artist Emu Hino and battles with various criminal organisations. He earned the sobriquet ‘Crying Freeman’ because of his idiosyncrasy of shedding a tear for each of his victims. The Crying Freeman manga became a cult work because of its stylised ultra-violence and often eroticised artwork. It was previously been adapted to the screen in five OVA anime, which appeared between 1988 and 1993 and closely followed the plotline of the original manga. There was a Hong Kong-made live-action film adaptation with Crying Freeman: Dragon from Russia (1990). (There was also the Hong Kong-made Crying Freeman: Killer’s Romance (1990), although this appears to simply be a gangster film and not related to the manga in any way).

This live-action Crying Freeman adaptation was produced by director Brian Yuzna, best known for films such as Society (1989), Bride of Re-Animator (1990), Return of the Living Dead III (1993) and The Dentist (1996), and directed by Frenchman Christophe Gans. Yuzna and Christophe Gans had previously collaborated and Gans had made his directorial debut on the Hotel of the Drowned segment of the H.P. Lovecraft anthology Necronomicon (1994). Crying Freeman was Christophe Gans’s first feature-length film and he would subsequently go onto make films like Brotherhood of the Wolf (2001), Silent Hill (2006) and Beauty and the Beast (2014), as well as to produce the ghost story Saint Ange (2004).

Having only seen Christophe Gans’ somewhat disappointing episode of Necronomicon prior to seeing Crying Freeman, one was considerably surprised by the things that he managed to do with the material here, turning out a film that dazzles with the flamboyant pyrotechnics of pure style. This begins even from the opening credits scene, which come overlaid against the wonderfully sensual image of the snake tattoo on a lithely muscled body coming to animated life. Christophe Gans has clearly borrowed from the book of stylistic tricks patented by John Woo. There is an amazing opening scene with Mark Dacascos pursuing two men through the woods and shooting each in slow motion, he tossing away his gun, which explodes behind him, and then putting out a hand to save a dumbfounded Julie Condra from falling off a cliff, saying his name and then having vanished by the time she turns around. There are other dazzling scenes, like the attack on Mako with cars going up in explosions and slow motion gun battles with masked assassins firing in mid-air; or images of Mark Dacascos waiting naked atop a doorframe for assassins to enter and throwing bottles of alcohol at people to ignite and incinerate them. Not to mention the incredible gun battles at the Hanaka headquarters and at the climax.

The film’s plot is certainly excessively complicated in the running around between the various factions. For the most part, Crying Freeman could almost be a silent film – the title character’s dialogue is stripped to next-to-nothing and the film exists almost entirely as a series of action set-pieces. Christophe Gans’s directorial delivery is extraordinary – he was one of the few Western directors to take on board the kinesis and self-conscious stylistic dazzle of Asian action cinema well before the Wachowski Brothers did.

The adaptation is a good deal more Westernised than the manga was. Christophe Gans lacks the melancholy and sense of ritual that was there on the comic-book page, while the element of eroticism in the strip has been thrown out altogether. Also, the characters have been cast with mostly Western actors, meaning that Emu Hino gets oddly renamed as Emu O’Hara. That said, the plot of the film follows the manga closely.