Crew

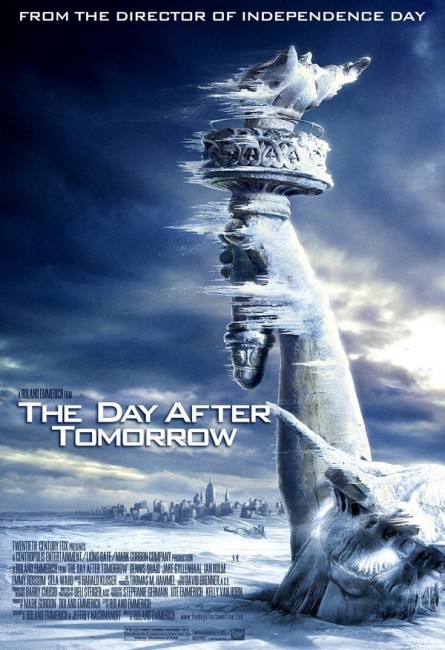

Director/Story – Roland Emmerich, Screenplay – Roland Emmerich & Jeffrey Nachmanoff, Suggested by the Book The Coming Global Superstorm by Art Bell & Whitley Strieber, Producers – Roland Emmerich & Mark Gordon, Photography – Ueli Stiegel, Music – Harald Kloser, Visual Effects Supervisor – Karen E. Goulekas, Visual Effects – Dreamscape Images, Hydraulix (Supervisors – Colin & Greg Strause), Industrial Light and Magic (Supervisors – Eric Brevig & Jim Mitchell, Animation Supervisor – Dan Taylor), Maestro F/X Inc (Supervisor – Adrien Morot), Ring of Fire Studios, Tweak Films (Supervisor – Christopher Howarth), yU+Co & Zoic Studio, Previsualization – Crack Creative, Special Effects Supervisor – Neil Corbould, Production Design – Barry Chusid. Production Company – Centropolis Entertainment/Lions Gate/Mark Gordon Co.

Cast

Dennis Quaid (Professor Jack Hall), Jake Gyllenhaal (Sam Hall), Emmy Rossum (Laura Chapman), Sela Ward (Dr Lucy Hall), Ian Holm (Professor Terry Rapson), Jay O. Sanders (Frank Harris), Dash Mihok (Jason Evans), Arjay Smith (Brian Parks), Glenn Plummer (Luther), Kenneth Welsh (Vice President Raymond Becker), Robin Wilcock (Tony), Austin Nichols (J.D.), Tamlyn Tomita (Janet Tokada), Perry King (The President), Adrian Lester (Simon), Sasha Roiz (Parker), Mimi Kuzyk (Secretary of State)

Plot

Palaeoclimatologist Jack Hall embarrasses the US Vice President before a United Nations conference on climate control, calling the US’s refusal to sign the Kyoto Accords and cut greenhouse gases ignorant. Immediately after this, a British colleague reports drastic lowering of temperature in the mid-Atlantic around Greenland, which is believed to be caused by melted chunks of the icecap falling into the ocean. This causes vast storms in the Northern Hemisphere with temperatures plunging to –170o, freezing people the moment they step out of doors. As the storms sweep the north of the US, Hall pushes the Vice President to evacuate people further south and this causes a panicked rush en masse across the border into Mexico. Hall’s son Sam is caught in New York City by mass flooding while on a school trip and takes shelter in the public library with friends. Others sheltered at the library decide to make the trip south, ignoring warnings that they will be frozen out in the open. Sam and a handful of others huddle for safety with little food as the city around them freezes over and they become buried under metres of snow. Meanwhile, Hall sets out on a dangerous trip overland from Washington D.C. to save Sam.

Director Roland Emmerich first appeared in his native Germany with films such as The Noah’s Ark Principle (1984), Making Contact/Joey (1986), Ghost Chase (1987) and Moon 44 (1990), before having a big breakthrough in the West with Universal Soldier (1992). Emmerich then went onto make increasingly larger scaled genre films, specializing in lavish, state of the art effects with the likes of Stargate (1994), the massive worldwide success of Independence Day (1996), the ill-regarded Godzilla (1998), the non-genre American War of Independence film The Patriot (2000) and subsequent to this, 10,000 BC (2008), 2012 (2009), the non-genre historical Shakespeare conspiracy film Anonymous (2011), the action film and White House Down (2013), the true-life gay rights drama Stonewall (2015), Independence Day: Resurgence (2016), the war film Midway (2019) and the disaster movie Moonfall (2022). While most of these, particularly Independence Day, were big successes, they were less effective as science-fiction films. Roland Emmerich has a bad tendency to sketch characterization in single dimensional clichés and rely solely on big scale effects and spectacle.

Roland Emmerich’s inspiration for The Day After Tomorrow came from The Coming Global Superstorm (1987), a non-fiction book by Art Bell and Whitley Strieber. In the book, Bell and Strieber put forth the case that fluctuations in the weather patterns are warnings signs of a superstorm that could sweep the Northern Hemisphere, creating winds of up to 200 miles per hour and a new Ice Age that would cover most of northern Europe and the US as far down as Washington D.C. They claimed that such superstorms had always heralded the onset of previous Ice Ages. The scientific community slammed Bell and Strieber for presenting a book that is heavy on theory and light on science.

An idea of the book’s basic credibility can perhaps be gleaned by looking at its two authors – Art Bell is a former host of a US-syndicated paranormal radio show whose greatest claim to fame was the dissemination of the notion that there was a UFO in the Halle-Boppe comet (an idea that was subsequently taken seriously by the Heaven’s Gate cult). Whitley Strieber was a former horror writer – see Wolfen (1981) and The Hunger (1983) – who claimed to have been abducted and anally probed by aliens and that he is able to pick up alien messages from an implant they left in his ear – see Communion (1989) – and that the information given to him about the future of climate change in The Coming Global Superstorm was provided to him by a mystery stranger that appeared to him in a vision in a Toronto hotel room. This perhaps says where the serious science in their book is coming from.

Even so, Roland Emmerich has had to throw out some of Bell and Strieber’s schlockier theories – they also made the Erich Von Daniken-like claim that one of their superstorms previously wiped out a highly technologically advanced civilization centred around Ancient Mesopotamia that left behind artifacts such as The Sphinx. [Although just as much as Bell and Strieber, Roland Emmerich must almost certainly have taken a big chunk of inspiration from the tv movie Ice (1998), which nearly prefigures the entire plot of The Day After Tomorrow].

In The Day After Tomorrow, Roland Emmerich has smartly critic-proofed himself from the accusations of bad science that dogged his previous films by both hiring a number of meteorological advisers and also publicly stating that he was perfectly aware that what the film depicts is scientifically nonsensical and that for the purposes of storytelling the actual period under which an Ice Age would occur has been dramatically condensed from decades and centuries to a matter of weeks. All its claims to merely being entertainment aside, The Day After Tomorrow wears a strongly pro-environmentalist heart on its sleeve – the end credits include promotion for the website www.futureforests.com, while Dennis Quaid’s hero is shown driving an electric car and the pre-release made much of the fact the film was entirely made using renewable resources.

What was interesting was the controversy that The Day After Tomorrow stirred. This began when, just before the film’s release, NASA forbade any of their scientists from commenting on the film and then promptly recanted their position when this only served to end up bring attention to the film and made them sound draconian. On the other side of the coin, both Greenpeace and the US liberal grassroots website www.moveon.org, in alliance with former Vice President Al Gore, who became the global poster boy for global warming a couple of years later with the documentary An Inconvenient Truth (2006), mounted an environmental awareness campaign in conjunction with the film. It is certainly good that The Day After Tomorrow ended up promoting an awareness of big issues like global warming. Although one cannot help but wonder if such groups were not doing themselves a disservice by associating themselves with crackpot pseudo-scientists such as Art Bell and Whitley Strieber and a film that wilfully confesses to its bad science.

I must confess that I liked The Day After Tomorrow a good deal better than I was expecting to. Independence Day and The Patriot both found the German Emmerich having become lost in adulation of the ideals of his adopted country, the US. Both films salute at the American flag with utmost reverence and solemnly believe that the country is a paragon of freedom and democracy. The moment the first live-action shot of The Day After Tomorrow turns out to be of the American flag, one sinks into their seat expecting more of the same.

Contrarily, in dramatic contrast to the flag-waving conservative American politics that have been written across Roland Emmerich’s earlier films in the boldest of red, whites and blues, The Day After Tomorrow comes with an interesting liberal agenda. It is surprisingly outspoken in its criticism of the George W. Bush White House’s record on environmentalism. There is a scene early on where Dennis Quaid’s climatologist slams the Vice President, played by Kenneth Welsh and made up to look suspiciously like Dick Cheney, for his failure to sign the Kyoto Accords with Welsh’s VP using exactly the same excuses as the Bush White House did – that doing so is bad for American business. Later Kenneth Welsh’s VP is all but called stupid for his poor knowledge of science.

In fact, there is something wittily subversive to the film’s political agenda. There is an hysterically funny scene later in the film where we see tv pictures of US citizens en masse illegally crossing the border into Mexico, something that is only permitted by the Mexicans when the President agrees to forgive all Latin American debt. Eventually by the end of the film, Roland Emmerich has Kenneth Welsh’s Vice President (now having become President) apologising to the rest of the world for having abused and exploited them in the past.

What is remarkable is how much Roland Emmerich’s politics have made a 180-degree turnaround between Independence Day and The Patriot to The Day After Tomorrow. Both Independence Day and The Patriot saw that what the country needed was a good old return to the values of the American flag and standing behind nationhood and a strong leader. By the time of The Day After Tomorrow, which is notably Roland Emmerich’s first film in a post-9/11, a post-Bush White House and a post-Iraq War USA, Emmerich is intriguingly questioning whether such bold nationalism and leadership is a good thing. Independence Day and The Patriot seem to say that America needs to reclaim its identity behind the country’s flag; The Day After Tomorrow shows the country cowered and beginning to severely question the way that it has treated the rest of the world. (This continues in Emmerich’s subsequent 2012, which comes out strongly in favour of the Obama White House and is about dismantling policies of elitist self-interest in favour of multi-lateral cooperation on a global scale). Perhaps all the difference comes in that this time out Emmerich does not have on board his co-producing, co-writing partner Dean Devlin, an American who has co-written all of his other films since Universal Soldier.

Its politics aside, The Day After Tomorrow is a much better film than Independence Day. It shows that Roland Emmerich has learned some of the failings of his earlier films. At least his comments on bad science recognise that such is a problem and offer a smart attempt to set aside the issue and acknowledge that he is making mass entertainment. In Emmerich’s favour, he does appear to have gone and researched some basics about climatology. Certainly, there is more of a stab toward at least pseudo– or quasi-credible science than in other disaster films like When Worlds Collide (1951), Armageddon (1998) or even the classic disaster novels of J.G. Ballard.

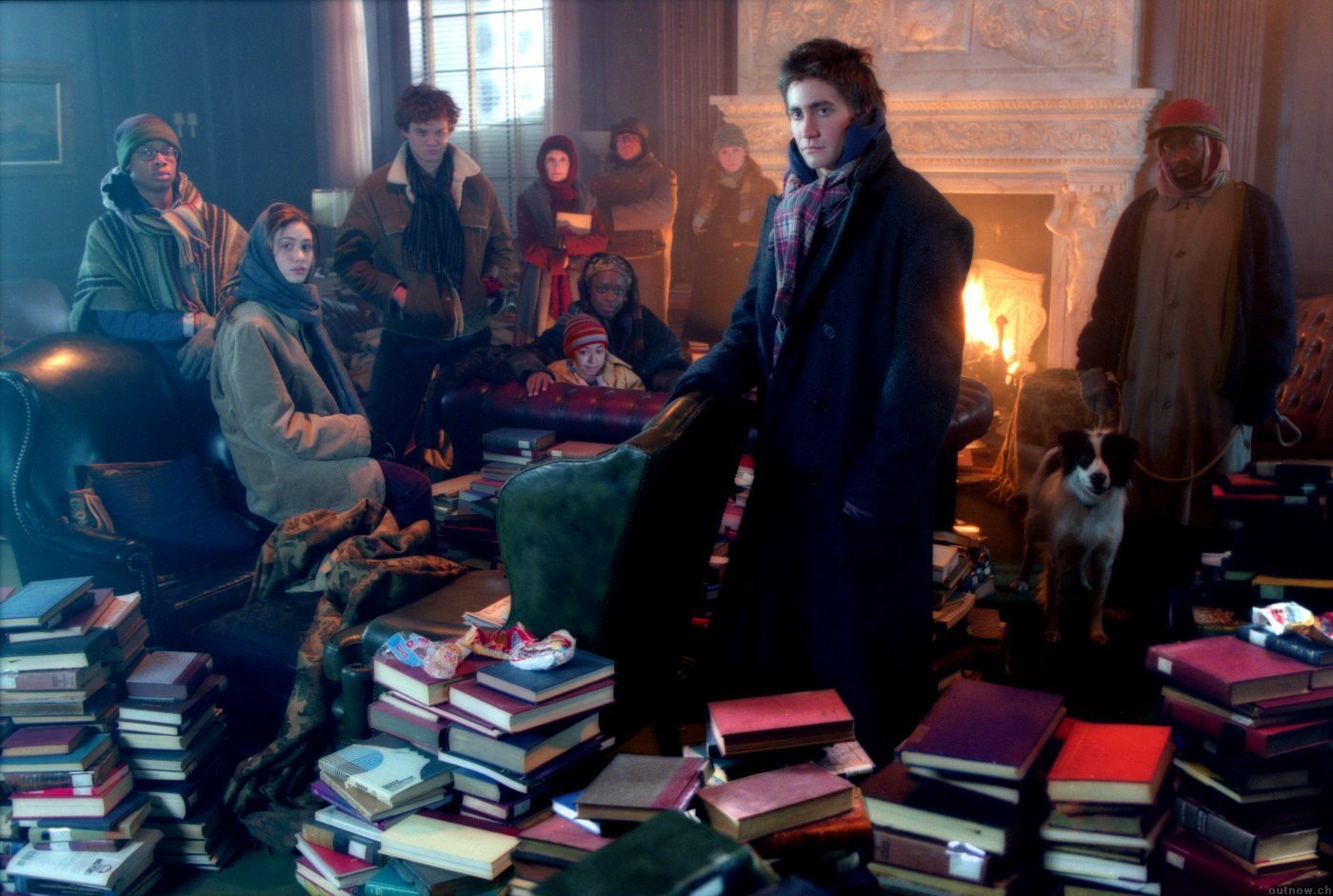

As such, The Day After Tomorrow is modestly effective science-fiction in the sense that Roland Emmerich has imagined a cataclysmic event and then offered a portrait of a familiar world turned upside down and the human responses to such. There are some fine small touches of survivalism to the film – the people sheltering in the New York Public Library burning books to keep warm and the one librarian who refuses to burn a copy of the Gutenberg Bible because of the importance it represents in terms of being the first ever published book; the problems of nobody knowing what to do during a medical emergency, necessitating a venture out onto the iced-over Manhattan streets where there become additional dangers of freed timber wolves; or Dennis Quaid’s walk across country where suddenly the glass of the frozen-over roofs of shopping malls proves a pitfall as deadly as any ice crevasse in the Antarctic. There are some fine images – the stunning effects shot of a camera circling the Empire State Building as a wall of ice freezes its way down; of the Statue of Liberty and all of Manhattan buried under snow; and especially the supremely weird image of a Russian freighter drifting through the streets of Manhattan, its hull scraping the submerged street and crushing taxis and buses underneath it.

Ultimately, Roland Emmerich still creates cliché characters. Most of the people in the film are the stock characters that populate disaster movies – the decent preppie kid, the good-hearted bum, the pompous authority figure whose self-interest is exposed by the disaster, the techno-geek, the likeable secondary character who sacrifices his life, the token sick kid. What is annoying is how the film skips over the surface of some of the characters, even in terms of the clichés they are written as. Emmerich almost seems too nice towards what in another film would be the bad guys of the show – the self-interested Vice President, the smooth preppie kid from the wealthy family trying to woo away Jake Gyllenhaal’s love interest, the guy who is more interested in making out than tending the weather monitors. Another filmmaker would grant them just desserts, Emmerich by contrast allows Kenneth Welsh’s Vice President a redemption at the end and never digs into the conflicts that might have arisen between Jake Gyllenhaal and his rival.

And on a wider scale, Emmerich never gives the resolution of the film adequate impetus. Stories that imagine would-shattering disasters always have a problem – most of the disasters on such a scale are too big to have any personal drama to them. It is near impossible to have a hero battling to save the world from destruction when the enemy they are fighting is a disembodied force like the weather. Emmerich sidesteps this by making the principal drama Dennis Quaid’s journey across country and Jake Gyllenhaal’s attempt to survive in the Library. Only these are not terribly satisfactory dramas. The Library survival drama lacks any harrowing sense of true survivalism in sub-zero temperatures – despite their ordeal, the people in the library manage to find enough water to remain shaven and clean, and we see little effect of their starvation. There is nothing here of the sense of people hanging on for their very lives – compare this to the stunning tv mini-series Shackleton (2001), the true life story of a group of 28 men who in 1914 were forced to survive five months of an Antarctic winter huddled underneath an overturned liferaft and to then hike 800 miles to find the nearest outpost of civilization.

Equally so, the resolution of the film comes with an almost miraculous flick of the plot hand, where the superstorm with seemingly absurd moment reaches a point of passover just as Dennis Quaid is climactically reunited with son Jake Gyllenhaal. There is no catharsis to the climax on a human level, just the reuniting of father and son then a cut away to Kenneth Welsh making his apology to the rest of the planet and a pullback to the Earth from space and an astronaut cryptically noting in awed tones that the air is now clean again. The implication it leaves us with is that if we can reach a point of redemption, if we can reunite with the children we have neglected and stop exploiting the world, then these things will miraculously pass. The whole point that climatologists have been making in their warnings about global warming is that if we don’t do these things now then it will no longer be possible to stop the onset of cataclysm and earn our redemption.

(Winner for Best Special Effects at this site’s Best of 2004 Awards. No. 5 on the SF, Horror & Fantasy Box-Office Top 10 of 2004 list).

Trailer here