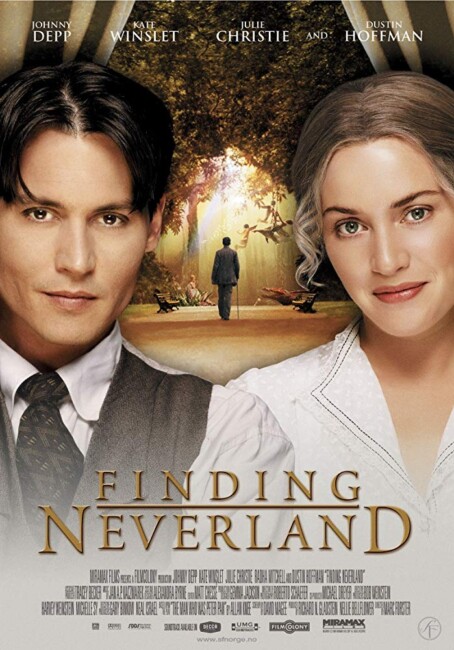

USA/UK. 2004.

Crew

Director – Marc Forster, Screenplay – David Magee, Based on the Play The Man Who Was Peter Pan by Allan Knee, Producers – Nellie Bellflower & Richard N. Gladstein, Photography – Roberto Schaefer, Music – Jan A.P. Kaczmarek, Visual Effects Designer – Kevin Tod Haug, Visual Effects – BUF, Double Negative (Supervisor – Paul Riddle) & Lost Boy Studios (Supervisor – Tony Power), Special Effects Supervisor – Stuart Brisdon, Production Design – Gemma Jackson. Production Company – FilmColony.

Cast

Johnny Depp (James ‘J.M.’ Barrie), Kate Winslet (Sylvia Llewelyn Davies), Radha Mitchell (Mary Ansell Barrie), Julie Christie (Emma du Maurier), Dustin Hoffman (Charles Frohman), Freddie Highmore (Peter Llewelyn Davies), Nick Roud (George Llewelyn Davies), Luke Spill (Michael Llewelyn Davies), Joe Prospero (Jack Llewelyn Davies), Kelly MacDonald (Peter Pan), Angus Barnett (Nana/Mr Reilly), Toby Jones (Smee), Mackenzie Crook (Mr Jaspers), Ian Hart (Arthur Conan Doyle), Oliver Fox (Gilbert Cannan)

Plot

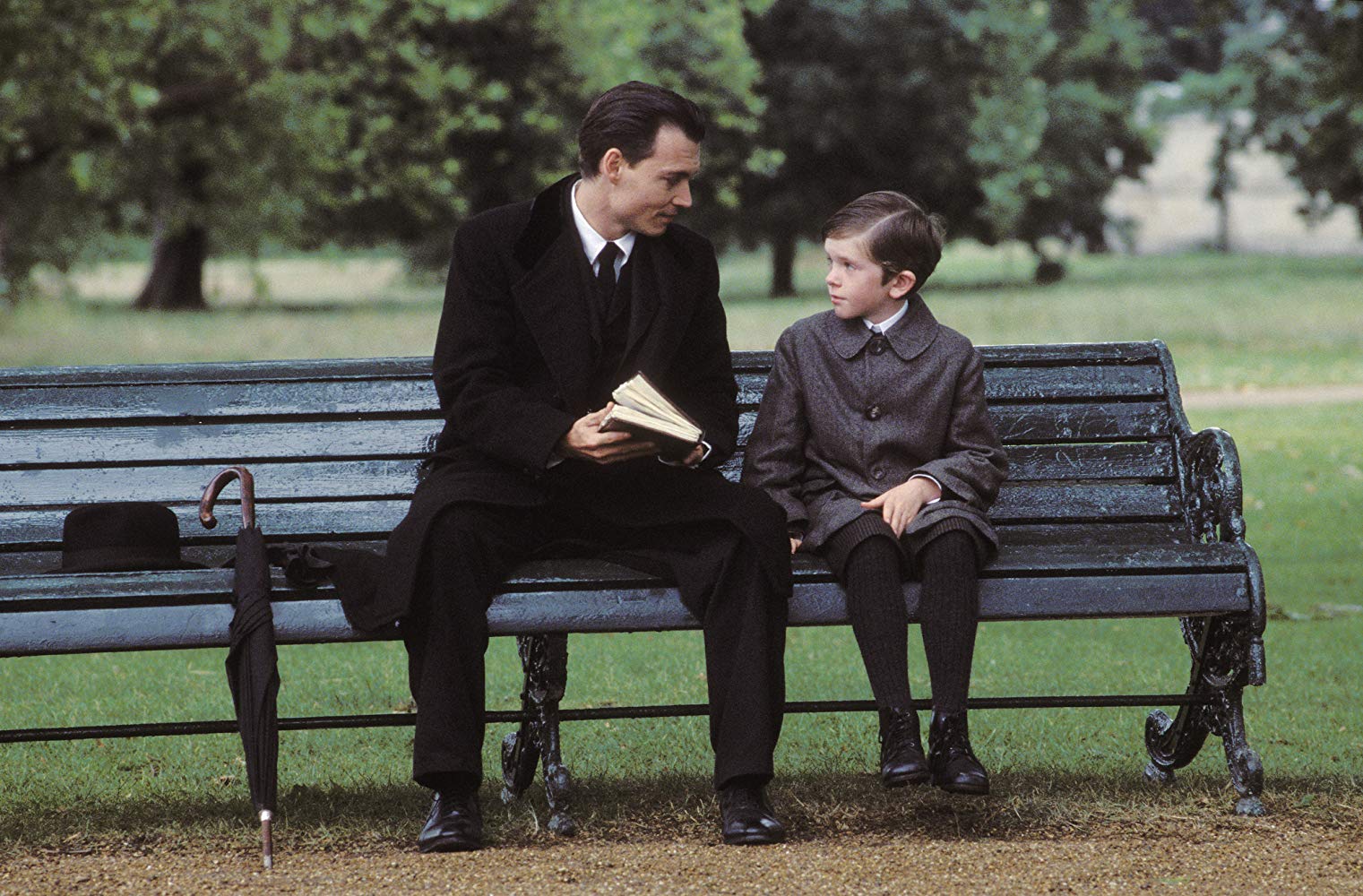

London, 1903. James or J.M. Barrie is not having much success as a playwright. While sitting in the park writing, Barrie meets widow Sylvia Llewelyn Davies and her four boys George, Michael, Peter and Jack and befriends them. He soon comes to spend all his time playing with the boys, creating wonderful adventures of pirates and Indians for them. Barrie’s wife Mary begins to feel neglected, particularly as gossip and social disapproval begins to grow about him spending his time in the company of another woman. Barrie is concerned most about the youngest Llewelyn Davies boy Peter who has suppressed his feelings about his father’s death. In trying to encourage Peter to come out of his withdrawal, Barrie comes up with the idea for a new play involving pirates, Indians and fairies that he decides to call ‘Peter Pan’.

Finding Neverland is a film based on the life of Scottish playwright James Matthew or J.M. Barrie (1860-1937). J.M. Barrie’s best known work is of course the play Peter Pan (1904), which is one of the most celebrated of all works of children’s literature. Finding Neverland emerged to rapturously acclaimed response, winning a prize upon its premiere at the Venice Film Festival and accruing a swag of best of the year awards, including Best Film from the National Board of Review and nominations in all the major categories (Best Film, Director, Screenplay, Actor) at the Golden Globes and Academy Awards. This acclaim from the critical and awards fraternity, and apparently by audiences too, left me scratching my head. I ended up finding Finding Neverland certainly a nice and well made film but far from a great one. (It was the similar case with director Marc Forster’s Monster’s Ball (2001), a film that enjoyed much critical and awards acclaim, but proved unexceptional when seen outside of the hype).

Part of the problem for me was Finding Neverland‘s approach. The film openly acknowledges on both the opening and closing credits that it is only “inspired” by true events and that it has happily condensed or eliminated characters for the sake of the story. One suspects that maybe Finding Neverland was being a little flattering of itself with such a description. In terms of adhering to the facts of the backstory about the writing of Peter Pan and biographical accuracy, Finding Neverland is more down around the level of Time After Time (1979), which had H.G. Wells building a time machine to travel to present-day San Francisco, or Shadow of the Vampire (2000), which postulated that Nosferatu (1922) was cast with a real vampire.

Most critics picked up on some of the surface details – such as that the film has created an entire fiction about Sylvia Llewelyn Davies’s husband Arthur having been killed, whereas in fact he was alive and well throughout J.M. Barrie’s friendship with the children (indeed, was present at the premiere of Peter Pan) and did not die until 1907; and that the film has also eliminated one of the Llewelyn Davies children, who were five rather than four in number, with the fifth Nicholas being born as the play was written – and have generally forgiven it for a few such liberalisms in the service of a wider story.

However, Finding Neverland‘s treatment of the facts is exceedingly more broad-minded than this. Certainly, Sylvia Llewelyn Davies did die and leave guardianship of the boys to J.M. Barrie, however this did not happen until 1910 and was not concurrent with the premiere of the play as the film has it. The friendship with the Llewelyn Davies children is reasonably accurate, although in actuality J.M. Barrie met the children in 1896, some seven years before Peter Pan was produced, not one year before. Moreover, the father never died when the film had him doing so, making the subplot about Peter’s suppressed feelings a complete fiction. Indeed, Peter was still in a stroller at the time that J.M. Barrie met him, not running around and playing with the other boys. (Also, it was the Llewelyn Davies nanny who was present when J.M. Barrie met the children and Barrie did not meet Sylvia until at a dinner party some time later).

Barrie’s wife Mary did not begin an affair with the writer Gilbert Cannan until 1909, four years after Peter Pan premiered (and more than a decade after Barrie met the Llewelyn Davies’) and not concurrent with the play’s writing as the film would have us believe. J.M. Barrie’s plays were not flops as depicted by the film and were in fact considerable successes, most notably The Admirable Crichton (1902) – moreover, rather than regarded as dull and dry, they were appreciated for their often biting adult satire. The American producer Charles Frohman (portrayed in the film by Dustin Hoffman) was not sceptical about Peter Pan‘s success but an enthusiastic backer who was happy to front the play’s considerable cost. Even the scene in the film where Barrie insists that 25 seats be given to orphans on the opening night is a complete fiction. The film also omits any mention of how J.M. Barrie originally premiered the character of Peter Pan in his adult novel The Little White Bird (1902) prior to writing the play.

I have never had a particular problem with films that fictionalise some aspects of historical truth to tell a better story – some good examples of films that have successfully done so might be Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), JFK (1991), Ed Wood (1994), Braveheart (1995) or The Hurricane (1999). The problem with Finding Neverland is not so much that it fictionalises some aspects of the true story but rather that it does so in a way that gives both an entirely inaccurate depiction of the person that J.M. Barrie was and the way that Peter Pan came into being. Certainly, one does not wish to downplay the importance of the Llewelyn Davies boys in being the locus of the creation of Peter Pan. Finding Neverland, even if it plays around with a good many of the facts here, at least captures something of the sense of Barrie’s love of playing with the boys and creating stories to wind them in as characters.

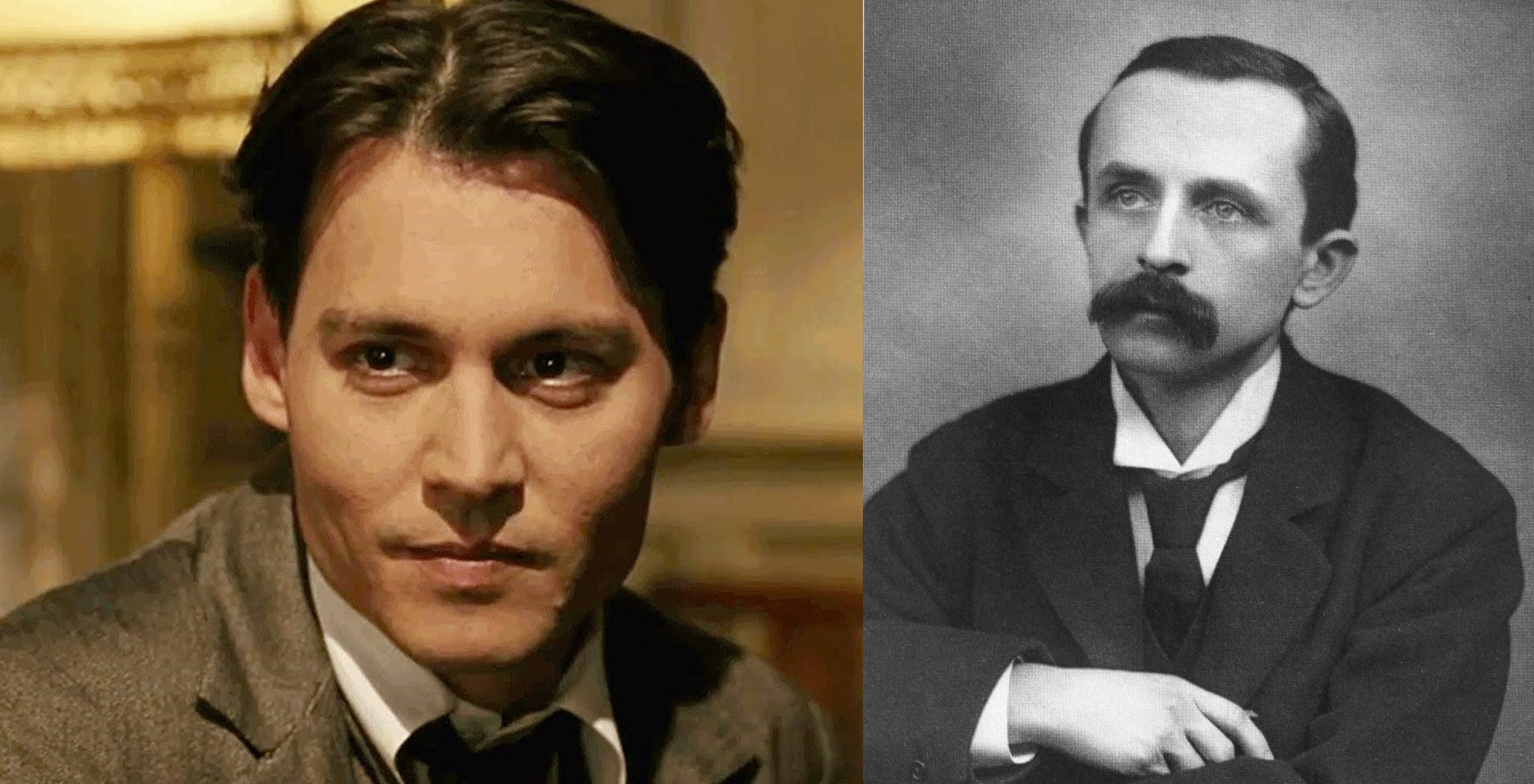

What seems to overshadow the film by its absence is almost any discussion of just how much Peter Pan was also integrally wrapped up in the character of J.M. Barrie himself. The depiction of Barrie we get, as played by Johnny Depp, is almost entirely at odds with the person that comes through in his biography. For one, the casting of the part of Barrie has been prettified for the film. J.M. Barrie would have been 44 years old when Peter Pan premiered, whereas Johnny Depp appears in his early thirties.

More to the point, J.M. Barrie was only five feet tall – it is often said that he was literally a boy who had refused to grow up – and existing photos show him balding. While Johnny Depp plays the part with an authentic Scottish accent, these other features have been eliminated and focus placed on Depp’s good looks and sexily draped cowlick. Aside from the physical disparity between Johnny Depp and Barrie, J.M. Barrie was also described as being painfully shy, which never comes across in the film.

Even more importantly, there are a great many aspects of J.M. Barrie’s psychological makeup that the film dismisses. Barrie was critically affected by the death of his brother David in a skating accident when he was six years old. His mother never got over the loss. Barrie felt alienated from her affection throughout his life and even went to the extent of dressing up as his brother (an incident that is briefly mentioned in the film, although the film gives the impression that this only happened once) and imitating his whistle and walk in an attempt to placate her. For Barrie, David always represented the ideal boy – the one who died before he ever had the chance to grow up and in his mother’s mind remained a perpetual child never aging. Barrie always pined for this state of lost childhood innocence – indeed, in the book Margaret Ogilvy (1896), a loving tribute to his mother, Barrie wistfully commented “Nothing that happens after we are twelve matters very much.”

J.M. Barrie also felt far more comfortable being around children than he did adults, which is what drew him to the Llewelyn Davies children. (Although, as the film correctly dismisses, there never appeared to be anything paedophile in his intent as he has sometimes been accused of). In his own marriage, Barrie appeared to be impotent and the failure of he and his wife to conceive became an issue that eventually caused their split – Barrie once told Mary the reason for this was that “boys can’t love” – and the friendship and adoption of the Llewelyn Davies boys was seen as a substitute for the family that Barrie could never conceive himself. While the influence of the Llewelyn Davies boys in the creation of Peter Pan is essential, Finding Neverland creates a complete fiction that J.M. Barrie based Peter Pan on Peter Llewelyn Davies’ denial of feelings over the loss of his father (who never died, at least when the film specifies he did), whereas the truth the film ignores was simply that Peter Pan was none other than J.M. Barrie’s wish fulfilment – the adult who wishes that he could forever be a boy and retain his lost mother’s affection.

In recent years there has grown a genre of biographical fiction concerned with travelling behind the writing/filming of celebrated works of literature and film. These biopics have tended to go in either of two ways. One of these is charting the disparity between the idealism of the works in question and the flawed lives of their authors – one could point to the genre likes of The Whole Wide World (1996) and The Passion of Ayn Rand (1999) in this instance. There is however another series of biopics that are either so much in awe of their subject matter (or too afraid of lawsuits from family members) to venture into telling their story in any way that is critical of their subject – examples might include the Danny Kaye Hans Christian Andersen (1952), John Carpenter’s Elvis (1979), The Jacksons: An American Dream (1992) and W. (2008) – and end up being so divorced from meaningful historical portrait that they should more correctly be regarded as adulation fantasies about their subject matter. Finding Neverland almost certainly falls amid the latter. What Finding Neverland has done is not so much tell an historical story about the creation of Peter Pan but rearrange the biographical details of J.M. Barrie’s life into a fantasy entirely of its own making derived out of the dichotomy between childhood and adulthood that runs through Peter Pan.

What disappointed me about Finding Neverland was how everything seemed cast into a series of simplistic divides – where people are seen either as being dour-minded adults who have lost their imagination and have a conservative fascination with what is proper behaviour or else have an unalloyed sense of childhood innocence. It seems a series of black-and-white divides with no middle path in between – the only adult in the film who seems in any way sympathetically portrayed, for example, is Kate Winslet’s Sylvia. It might be possible to create another reading for the film – that J.M. Barrie was someone was extraordinarily naive in his pursuit of child-like innocence and constant denial of adulthood that it drove the adults around him away. Indeed, the end that Finding Neverland reaches where Barrie tells Peter that his mother has gone off to Neverl and that all he has to do to realise that she is still there is close his eyes and believe seems entirely a child-like denial of the adult reality of death, not a coming to acceptance with it.

Director Marc Forster subsequently onto stay in genre territory with the deathdream fantasy Stay (2005); the fine meta-fiction Stranger Than Fiction (2006) in which Will Ferrell discovers that he is a character in a novel; the James Bond film Quantum of Solace (2008); the zombie film World War Z (2013); and returned to classic children’s stories with Christopher Robin (2018).

The film adaptations of Peter Pan include:- the classic Disney animated version Peter Pan (1953); Peter Pan (1955), a live tv play; Peter Pan (1976), a tv movie version with Mia Farrow!!! playing Peter; the animated tv series Peter Pan and the Pirates (1990); Peter Pan (tv movie, 2000); the big-budget live-action Peter Pan (2003) and the Disney live-action remake Peter Pan and Wendy (2023). There was also the fascinating but little-seen Neverland (2003), which gave Peter Pan a modernised interpretation with Peter a kid suffering from bipolar disorder; the tv mini-series Neverland (2011), which offered a science-fictional rationalisation set on an alien planet; and the modernised Wendy (2020), which relocates the story in the Mississippi Delta. Other variations of the story include:- Steven Spielberg’s live-action sequel Hook (1991), which concerns itself with a grownup Peter’s return to Never-Never Land; Disney’s animated theatrical sequel Return to Never Land (2002) and the series of Tinkerbell dvd-released films with TinkerBell (2008), Tinker Bell and the Lost Treasure (2009), Tinker Bell and the Great Fairy Rescue (2010), Secret of the Wings (2012), The Pirate Fairy (2014) and Tinker Bell and the Legend of the Neverbeast (2014); and the live-action prequel Pan (2015).

Trailer here