USA/Germany. 2003.

Crew

Director – Stephen Norrington, Screenplay – James Dale Robinson, Based on the Graphic Novels by Alan Moore & Kevin O’Neill, Producers – Trevor Albert & Don Murphy, Photography – Dan Laustsen, Music – Trevor Jones, Visual Effects Supervisors – David Goldberg, Janek Sirrs, Thomas J. Smith & John E. Sullivan, Visual Effects – Asylum, Big Red, Christov Effects, CIS Hollywood, Computer Cafe Inc (Supervisor – Scott Gordon), Cullen Film Effects, Digiscope (Supervisor – Dion Hatch), Double Negative (Supervisor – Paul Franklin), Engine Room, Industrial Light and Magic (Supervisor – Tim Alexander), Mar Vista Ventures, Millinium, Modern Video Film, Pixel Magic (Supervisor – Raymond McIntyre Jr), R!ot (Supervisor – Kenneth Nakada), Tippett Studios (Supervisor – Brennan Doyle) & VCE.com/Peter Kuran, Miniatures – Cinema Production Services (Supervisor – Michael Joyce) & New Deal Studios (Supervisor – Matthew Gratzner), Special Effects Supervisor – Terry Glass, Makeup Effects – Steve Johnson’s Edge EFX, Production Design – Carol Spier. Production Company – 20th Century Fox/Mediastream III.

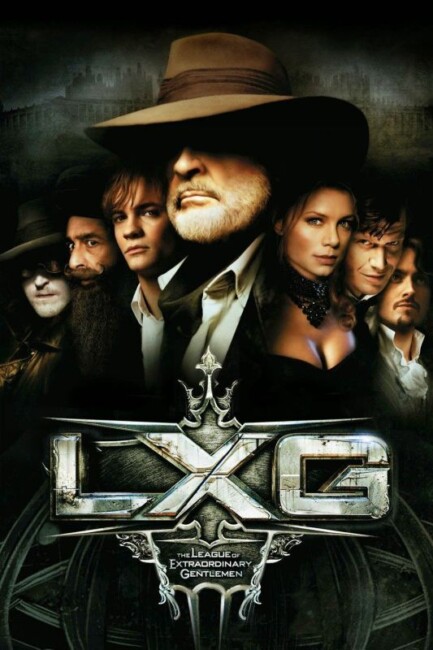

Cast

Sean Connery (Allan Quatermain), Shane West (Tom Sawyer), Naseeruddin Shah (Captain Nemo), Peta Wilson (Mina Harker), Stuart Townsend (Dorian Gray), Jason Flemyng (Dr Edward Jekyll/Mr Hyde), Tony Curran (Rodney Skinner), Richard Roxburgh (M), Tom Goodman-Hill (Sanderson Reed), Terry O’Neill (Ishmael)

Plot

1899. Both England and Germany are subject to raids by a masked, deformed criminal known as The Phantom who uses highly advanced tanks to burst into the Bank of England, as well as abduct German scientists. In Africa, the now aging adventurer Allan Quatermain is approached by the British Government who want his help before the situation descends into an international war. Back in England, the government agent known as M inducts Quatermain into The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, which is peopled by persons of exceptional abilities. Also recruited are the Indian inventor Captain Nemo; the vampiress Mina Harker; Rodney Skinner, a chemist who has taken an invisibility potion; the immortal and unaging libertine Dorian Gray; the youthful American secret agent Tom Sawyer; and Dr Henry Jekyll who has a formula that turns him into a rampaging beast. As the expedition sets out aboard Captain Nemo’s submarine The Nautilus to stop The Phantom from sabotaging an international conference in Venice, it is discovered that one of the League is a traitor and that The Phantom is manipulating the group’s purpose in being there.

There is an entire genre of fantastic literature that devotes itself to a speculative game where it is imagined that fictional characters all inhabit the same alternate universe and what might happen should they meet up. Although Sherlock Holmes pastiche writers had been playing this game for years, it was Philip Jose Farmer and his Wold Newton stories that popularised this form of fiction. A substantial part of Farmer’s fiction plays this game, with novels like Lord Tyger (1970) about the anthropologically realistic attempts to create a Tarzan; The Wind Whales of Ishmael (1971) where Herman Melville’s Ishmael ends up whaling on an alien planet; The Other Log of Phileas Fogg (1973), which sets an alien invasion in and around the inconsistencies of Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days (1872); The Adventures of the Peerless Peer (1975), which pairs Sherlock Holmes and Tarzan; A Barnstormer in Oz (1982), which deconstructs L. Frank Baum’s Oz books; as well as an entire series – the hilarious A Feast Unknown (1970) and its sequels Lord of the Trees (1970) and The Mad Goblin (1970), which offer up thinly disguised adventures of Tarzan and Doc Savage; while Farmer’s ongoing Riverworld series speculates about the meetings of various historical personages in the afterlife. It was however with his two cod-biographies – Tarzan Alive (1972) and Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Life (1973) – that Philip Jose Farmer created the Wold Newton universe wherein he speculated that an extraordinary range of popular culture heroes were related, interbred and sometimes even the same person operating under an alias.

This kind of literary game has proven amazingly popular since with authors such as Fred Saberhagen, Donald F. Glut, Ron Goulart, Craig Shaw Gardener, Lin Carter, K.W. Jeter, Christopher Priest, Nicholas Meyer and others bringing together various fictional characters, usually from Victorian era fiction or pulp authors like Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer and H.P. Lovecraft. The trend shows no sign of stopping with recent publishing success such as Greg Bear’s Dinosaur Summer (1998), set in the aftermath of Professor Challenger’s lost world expedition, and Kevin J. Anderson’s Captain Nemo (2001), which ties together most of the characters from Jules Verne, to Kim Newman’s remarkable Anno Dracula books, which move from the Victorian era through to the present in which Newman ties every conceivable fictional and historical character into an alternate world populated by vampires.

Both Marvel and DC Comics had been conducting the Wold Newton game for years with various team-ups from their superheroic pantheons and fictional characters. However, it was Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series of graphic novels begun in 1999 that took this almost to an obsessive level. [Alan Moore is one of the finest of the modern generation of graphic novelists, having written two modern classics – the famous Batman graphic novel The Killing Joke (1988) and the legendary Watchmen (1987), as well as other series such as Miraclemen. His works have become the basis of a number of film adaptations in the 00s with the likes of From Hell (2001), V for Vendetta (2006), Watchmen (2009), the Mogo Doesn’t Socialize and Tygers episodes of Green Lantern: Emerald Knights (2011, Batman: The Killing Joke (2016) and the tv series Watchmen (2019)]. The graphic novel version of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen has a much more detailed line-up of famous fictional guest stars than the film version does – also spotted can be appearances from Jules Verne’s Robur, H.G. Wells’s Professor Cavor, Edgar Allan Poe’s August Dupin, characters out of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1903) and the What Katy Did books, among numerous others. The second series of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen graphic novels pits the League up against the Martian invasion from H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898) – not just Wells’s Mars but one that also harmonizes Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Barsoom and Malacandra from C.S. Lewis’s Out of the Silent Planet trilogy, as well as Lieutenant Gulliver Jones from Edwin L. Arnold’s stories and Michael Moocock’s Mars stories. The popularity of the graphic novels also saw the creation of a role-playing game and has even spread to a (now defunct) amazingly detailed fan website that debates in extraordinary minutiae the references that Alan Moore has littered throughout the background of the series.

The film version of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is a more variable affair. There is the distinct sense that Alan Moore’s game playing with Victorian fiction has been dumbed down. The film is disappointingly stripped of many of the other characters and references that Moore made – we do get an appearance of Ishmael from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851) as Nemo’s companion; there is a cute link up between the rampaging Mr Hyde and the ape in Edgar Allan Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841) (although, as below, a reference that has to substantially distort the bulk of the Poe story); Richard Roxburgh appears as the predecessor of what is presumed to be M from the James Bond stories; and Quatermain gets a throwaway reference to Phileas Fogg’s journey around the world in 80 days. The film also has a far less complicated plot than the one that Alan Moore swings in the graphic novels. Out has gone the secondary villain of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu. Out also has gone the character of Campion Bond, the ancestor of James Bond. In comes the character of Tom Sawyer (who never appeared in the graphic novels) who has notedly been written in to essentially fulfill Campion Bond’s place because the producers statedly feared the line-up of non-American characters would alienate transatlantic audiences. Of course, this is not a Tom Sawyer that Mark Twain/Samuel Clemens is likely to recognize – it’s a Tom Sawyer a few years on who is now a US government agent, a crack six-gun shooter and gets throughout the course of the film to stunt-drive a customized Rolls Royce Silver Ghost (upon getting behind the wheel for the first time).

This is to a large extent symptomatic of the problems with The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Fun and all as Alan Moore’s game of literary line-ups and name-droppings is, it is one that has to ignore essential details or at least distort the original characters. This is particularly noticeable here – in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), Dorian Gray was a cad and a libertine who was eternally youthful because his aging and immorality had been transferred onto a portrait; in Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Dr Jekyll was a nobly upstanding doctor who devised a potion that brought out his brutish animal instincts. Both of these stories are essentially Victorian morality plays about the war between socially upheld virtue and the repression of carnality. Moreover, in both cases, the respective authors kill the title characters off at the end of the story. In The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen they not only survive but in one character’s case a new death is devised for him.

Even more noticeably, the film pushes the characters out of shape to now become essentially superheroes. Dorian Gray is not merely eternally youthful but has also picked up an invulnerability to bullets and sword cuts, while gaining an Achilles Heel that Oscar Wilde never gave him – to look upon his portrait will destroy him (whereas in the book he is more mundanely killed when the portrait is stabbed). Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde now emerges as a variation on The Incredible Hulk – indeed the three-metre tall Hyde that Jekyll transforms into is uncannily like the Hulk that turned up in Ang Lee’s Hulk (2003) around the same time – where Jekyll is not so much fighting against the beast within but merely trying to redeem the beast so that he can be made to fight on the side of good. Captain Nemo goes from being a brooding anti-hero-come-terrorist to heroic stalwart of the mission. Considering that Jules Verne had Captain Nemo as a vigilante of the seven seas who actively destroyed all ships of war, having Nemo set sail here to save a collected gathering of international ministers of war seems ever-so-slightly a betrayal of the essence of the character. (It is nice however to see Captain Nemo portrayed as a Hindu in keeping with the origin story that Jules Verne outfitted him with in Mysterious Island [1875]). For reasons unknown, the Invisible Man here is a different Invisible Man to the one in the graphic novel. There the Invisible Man was the same one from the H.G. Wells novel The Invisible Man (1897). Here he is another scientist who has perfected the formula and removed the madness-inducing effects – in so doing, the film actually makes this Invisible Man a character who perfectly dovetails in with the original, rather than having to conveniently ignore the fact that H.G. Wells killed his Invisible Man off at the end of the story and that the drug made him a raving megalomaniac, as Alan Moore had to do.

The upfront news on The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen film did not seem at all promising – the dumbing down of the story, the introduction of a character for American mass-appeal, a muchly troubled production including the sets in Venice being flooding. Most of all, there were the stories of on-set squabbling between Sean Connery, who takes an executive-producing role on the film, and director Stephen Norrington. Various stories emerged that Connery was concerned about Norrington’s slowness of approach and disliked being made to endlessly wait around on set. Other stories were less kind to Stephen Norrington and called him a bad-tempered, bawling martinet. The situation descended to the point where Connery and Norrington would not talk to one another during shooting and communication would only go through intermediaries, with Norrington at one point purportedly inviting Connery to punch him. Norrington even boycotted the film’s world premiere, where in his absence Sean Connery loudly commented to the press that Norrington would be better off placed in an asylum. It all seemed like a disaster in the anticipating on the order of The Island of Dr Moreau (1996).

All things said, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen works better than it looked like it was going to. That the film works directorially and that Sean Connery manages to emerge with dignity throughout is surely a testament to professionalism on everybody’s part. Stephen Norrington began in the industry working on the effects crews for British-shot films like Return to Oz (1985), Aliens (1986), Hardware (1990), The Witches (1990) and Alien3 (1992). He first appeared with the excellent low-budget killer robot effort Death Machine (1995) and then went onto the big-budget vampire film Blade (1998) (which was also a comic-book adaptation). He mounts The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen as an adventure film – no more than that, no less. For all the twisting of the characters out of shape to make up a sort of Victorian superheroic pantheon, the script makes a fair effort to get inside them, most successfully being the relationship between Sean Connery’s aging Allan Quatermain and Shane West’s youthfully enthusiastic Tom Sawyer. Norrington shows a clear flourish with the effects and action sequences, most exhilarating being a car race through the collapsing streets of Venice.

The unexpected scene-stealer of the entire film however proves to be David Cronenberg’s regular production designer Carol Spier. From the breathtaking new Nautilus cruising through the oceans and its interior all lit up in pure white like a raj’s palace, to gloomy Victorian libraries, the villain’s factories of tanks stretching as far the eye can see, and gaslit London and Venetian exteriors that look far more brooding and dazzlingly fabulous than probably the real things ever were, the work that Carol Spier does is utterly stunning and is the real star of the show.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is the last film that Stephen Norrington has made to date. At one point, it was claimed that he had retired, although his name has since been associated with other works such as the remakes of Clash of the Titans (2010) and The Crow (1994), although in both cases was replaced by other directors.

(Winner for Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 2003 Awards).

Trailer here