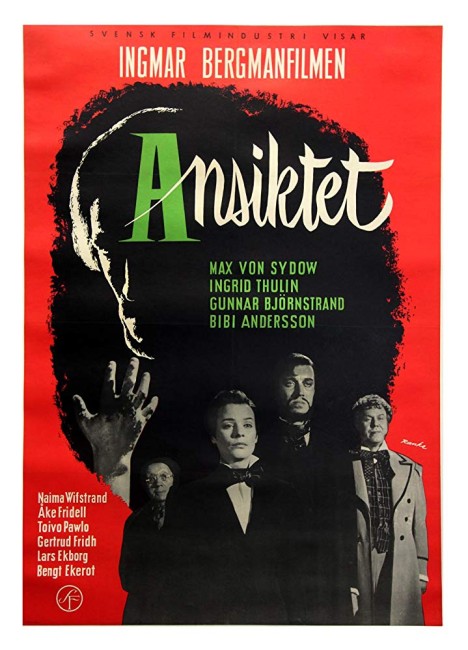

aka The Face

(Ansiktet)

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Ingmar Bergman, Photography (b&w) – Gunnar Fischer, Music – Erik Nordgren, Art Direction – P.A. Lundgren. Production Company – Svensk Filmindustri.

Cast

Max Von Sydow (Albert Emanuel Vogler), Ingrid Thulin (Manda Vogler/Aman), Gunnar Bjornstrand (Dr Vergerus), Åke Fridell (Tubal), Erland Josephson (Consul Egerman), Naima Wifstrand (Granny), Toivo Pawlo (Chief Starbeck), Gertrud Fridh (Ottila Egerman), Lars Ekborg (Simson), Bibi Andersson (Sara), Sif Ruud (Sofia Garp), Bengt Ekerot (Johan Spegel), Oscar Ljung (Antonsson), Birgitta Pettersson (Sanna), Ulla Sjoblom (Mrs Starbeck)

Plot

Sweden, 1846. Vogler’s Magnetic Health Theater, a travelling show led by the charismatic and mute magician Albert Vogler, arrives in a small town to give a performance. However, the local authorities have heard of their reputation elsewhere and are determined to prove that Vogler and associates are charlatans. While housed at the home of the councilman Egerman, Vogler and his entourage and their claims to be able to do magic have a seductive effect over Egerman’s wife and the servants.

Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007) was probably one of the greatest directors of the 20th Century. Born in Uppsala, Sweden, Bergman grew up in a staunch Lutheran family – his father was chaplain to the court of Sweden. Bergman developed an interest in theatre after someone gave him a magic lantern at the age of ten. This blossomed into a lifelong interest in the magic of make-believe – indeed, Bergman entitled his biography The Magic Lantern (1988). He would stage his own home puppetshows for the family and then went on to study theatre at university, becoming the youngest theatre manager in Europe at the age of 26. He began writing films in the mid-1940s and made his directorial debut with Crisis (1946).

Bergman’s international acclaim first came with the romantic comedy Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) and this was followed by extraordinary Wild Strawberries (1957). In the 1950s, Bergman embarked on a body of work that moved through the likes of The Seventh Seal (1957), this, The Virgin Spring (1959), Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1962) and The Silence (1963). In these films, Bergman articulates a series of meditations that deeply question the nature of religion in the modern world. They are films where Bergman despairs of meaning in a world where he can no longer believe in God and sees only suffering and pain inflicted on humanity by itself. Bergman later moved away from such preoccupations and his films of the 1970s, while no less heavy and weighted, concern themselves more with the complexity of repressed emotion within families and marriages.

Whatever period of work ones comes to Ingmar Bergman through, there is something exceptional to his films – be it the profundity of philosophical/religious discourse he engages in, the depth of the characters he manages to convey on screen, and the sense of their pain and innermost selves opened up. In The Magician, Bergman’s greatness is his evocation of the characters – the mephistophelean presence of the sickly Max Von Sydow; the cocky Tubal; the androgynous Aman; the haughtily hypocritical ministers.

Bergman’s art is not even necessarily his ability to offer penetrating character analysis but rather to cast actors perfect for the parts and to reveal everything through the dialogue. The scenes where Max Von Sydow must confront the counsellors, or the scenes in the kitchen where we see the intensity of the old hag and the charm of Tubal the seducer are exceptional.

What Bergman then does, having so effectively sketched such people, is to reverse things and show us the charlatanism underneath – the old hag is just selling fake potions and substituting rat poison unknowingly to her buyers; Max Von Sydow has been faking his muteness; Ingrid Thulin’s androgyne assistant is a woman dressed as a man; and during Von Sydow’s performance a curtain is accidentally swept aside showing his levitation to be a parlour trick being conducted with wires.

If one understands Bergman’s intent correctly, he is making a film here about the necessity of stage illusion even in the face of charlatanism. While most films on this topic – Séance on a Wet Afternoon (1964), Black Rainbow (1989) – take the contrary view, that it is necessary to parse the illusion away to reveal the naked truth, Bergman sees it the other way around. The film is an extension, almost arguably a corollary to Ingmar Bergman’s previous film, the extraordinary The Seventh Seal. In The Seventh Seal, Bergman attacked the illusion of religion in a world of pain and suffering. Here though he turns around and attacks scientific reductionism and smug middle-class certainty as hypocritical and sees illusion as something that is a necessary and vibrant alternative. (He still manages to get a few characteristically stinging attacks in at religious dogma: “The clergy are in the same boat,” he says at one point. “God is silent and the humans babble”).

Bergman is captivated by the seductive power of the illusionists – the sexual thrall that Max Von Sydow manages to unwittingly hold over Egerman’s wife Gertrud Fridh; Tubal’s charming the servant girls; and one scene where Von Sydow manages to hypnotise a bulky manservant into believing that he is imprisoned in chains and cannot move.

The point the film eventually arrives at is a far more ambiguous one than in The Seventh Seal. It is one where Bergman sets up a dialectic that shows the town counsellors and their rationalist reductionism as pompous and hypocritical and the magicians as vital, but where eventually in the end the magicians are shown to be flawed and weak when stripped of their illusions – Max Von Sydow is gradually pared away from his intense charisma to be shown as a pathetic individual; while the character of Tubal, after having plied his charms and seduced the servant girl, is then shown to be easily ordered about by her at the end.

Though the film is only debatably a fantastic one, Bergman conjures an intensely haunted atmosphere. There is the character of the actor who is murdered in the coffin and then later appears to return from the dead – although the film, or maybe the subtitling, is not exactly clear what is going on here. The opening moments with the carriage journey through the woods contains a genuinely haunted atmosphere. Here Bergman and cinematographer Gunnar Fischer offer beautifully gloomy images of the carriage passing against a stark sky and through a dark forest, lit up by spindles of light coming through the trees; of the travellers claiming to hear ghosts and screams (something that we the audience never do) and the old hag muttering spells. Max Von Sydow finds a dying man and takes him into the carriage and watches in intense anticipation as the man reports feeling death creeping up his body and then offers the unfinished revelation that “Death is …” before expiring.

The scene in the attic at the climax is a superbly haunted one that almost certainly passes over into horror territory with images of eyeballs in an inkpot, a hand falling on the desk and continuing to pop up all over the place, and what might be the ghost of Max Von Sydow appearing in the mirror and pursuing Vergerus. Even if the film’s resolution is mundane, Bergman for a time definitely suggests something supernatural in these scenes.

Many of the elements here are ones that recur throughout Ingmar Bergman’s work. He repeatedly used the names of Vergerus and Vogler for characters in other films. There is much of his distaste for the clergy and authoritarian petty bourgeoisie hypocrisy; there is his fondness for the illusion of theatre and magic shows; his love of big houses with extended interrelated families all living together; and the fascination with androgynous people. Many of the motifs here would later turn up in his magnum opus Fanny and Alexander (1982).

Ingmar Bergman’s other films of genre interest are:– The Seventh Seal (1957), a staggering and profound meditation on religion with a knight meeting with Death; the revenge film The Virgin Spring (1959); The Devil’s Eye (1960), a comedy about The Devil sending Don Juan to tempt a vicar’s wife; Hour of the Wolf (1968) about an artist for whom reality and nightmare begins to blur; the acclaimed adaptation of Mozart’s opera fantasy The Magic Flute (1975); and the family saga/ghost story Fanny and Alexander (1982).

Trailer here