(Fanny och Alexander)

Sweden. 1982.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Ingmar Bergman, Producer – Jörn Donner, Cinematography – Sven Nykvist, Music – Daniel Bell, Special Effects – Bengt Lundgren, Art Director – Anna Asp. Production Company – Svensk Filminstutet.

Cast

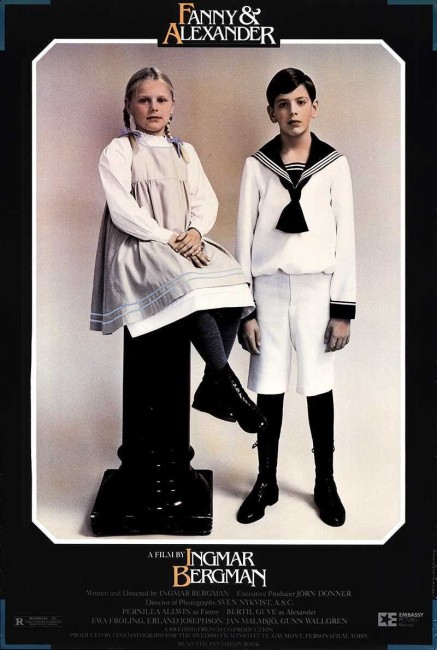

Bertil Guve (Alexander), Pernilla Allwin (Fanny), Ewa Fröling (Emilie), Jan Malmsjo (Edvard Vergerus), Gunn Wallgren (Helene Ekdahl), Jalle Kulle (Gustav Ekdahl), Pernilla Wallgren (Maj), Erland Josephson (Isak Jacobi), Allan Edwall (Oscar Ekdahl), Mona Malm (Alma Ekdahl), Boerje Ahlstedt (Carl Ekdahl), Christina Schollin (Lydia), Stina Ekblad (Ishmael)

Plot

The Ekdahl clan, headed by the matriarch Helene, along her three sons, their wives, children and mistresses, gather for Christmas Day of 1907. While they are there Oscar, one of the sons, the manager of the family theatre, has a heart attack and dies. Several months later, his widow Emilie agrees to marry the local Lutheran minister Edvard Vergerus. Vergerus convinces Emilie to give up all their belongings and move into his house with her two young children Fanny and Alexander. Once there, Vergerus imposes a cruel and rigidly ascetic lifestyle on them, punishing them harshly for the slightest infringement. Emilie realizes her mistake but is unable to leave, as the authorities will only repatriate runaway wives and take away her children. Oscar’s ghost then appears to Alexander, telling him how Vergerus locked up and starved his previous wife.

Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007) was one of cinema’s great directors. Bergman’s work has become synonymous with matters of great intellectual weight and oppressive melancholy. When Ingmar Bergman came to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s, his films dealt with grand philosophical questions – the meaning of suffering in a godless universe, questions of subjectivity and realism – that seemed far away from any Hollywood subject. Bergman works like the remarkable Cries and Whispers (1972) seem like a single anguished cry of deep pain, the cinematic equivalent of an Edvard Munch painting, that scour emotional depths no English-language director comes near.

Ingmar Bergman made Fanny and Alexander at the age of 64 and announced it would be his last film – he subsequently directed only theatre and several tv movies up until his death in 2007. Fanny and Alexander is like an enormous loosely autobiographical tapestry upon Bergman’s part, winding in the predominating themes that have graced his work – the harsh and authoritarian religious upbringing (his father was a Lutheran minister), the formative influence of theatre and puppetry (he directed plays and puppet shows at home as a teenager and became a theatre director before he was a filmmaker), the essential magic of the imagination, the extended families and their mutual pains and joys. Fanny and Alexander was a fitting swan song for Ingmar Bergman and is one of his greatest works.

While much of Ingmar Bergman’s earlier work tends to weigh down in intellectual gloom, Fanny and Alexander is a sublimely warm and happy film. The scenes of the extended family clan are evoked with an extraordinary richness, both on a visual level and in the warm, occasionally bawdy characterizations of some of the family. Sven Nykvist’s photography deservedly won that year’s Academy Award – he and Bergman dress the household with extraordinary detail. There is one exquisite shot tracking down a street where each window comes filled with hundreds of lit candles.

This of course comes at pointed visual contrast to the second half of the film where the rich reds, golds and greens of the Ekdahl household come at stark antithesis to the bare grey austerity of the Vergerus home. Bergman confirms his directorial mastery in the intense, frighteningly pitched confrontations between Vergerus and Alexander. There is, as always, an extraordinary power to Bergman’s direction, none more so than the single shot that tracks the two children as they follow a horrible screaming through the house in the middle of the night to eventually arrive at their mother wailing over Oscar’s casket.

As with much of Ingmar Bergman’s work, there comes a magical evocation of fantasy – from the matter-of-factly accepted ghosts that appear throughout to Ishmael, the spookily androgyne psychic with shaven eyebrows, who shows Alexander how to free himself by unleashing his psychic powers. There is an extraordinary abundance of imagery in the film – too much to explore here. One of the most striking allusions is to Hamlet – which notedly the father dies performing – that subsequently hangs over the film like a story frame – after dying the father returns to his son as a ghost, providing Alexander/Hamlet with information about how Vergerus/Claudius, who has now married Alexander’s mother, killed his previous wife. All of this makes for a particularly chilling twist ending.

Ingmar Bergman originally made Fanny and Alexander as a five-hour plus production for Swedish tv. This was released outside the country in a condensed 188-minute cinematic version. The film version is available in a badly dubbed American version and a superior international subtitled version. The original five-hour version was finally given a DVD release in 2002. Certainly, the condensed cinematic version holds up remarkably well on its own – the only noticeable difference is the character of the self-despising drunkard son Carl and his German wife who seem to drop off and be forgotten about. The film won Ingmar Bergman his fourth Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.

Ingmar Bergman’s other genre films are:– The Seventh Seal (1957) about meetings between a knight and Death incarnate; The Magician/The Face (1958), about a magical performing troupe who have reputed supernatural powers; the revenge film The Virgin Spring (1959); The Devil’s Eye (1960), a comedy about The Devil sending Don Juan to tempt a vicar’s wife whose purity offends him; Hour of the Wolf (1968) about a tormented artist’s hallucinations come to life; and the acclaimed adaptation of Mozart’s opera fantasy The Magic Flute (1975). All are recommended with the highest praise.

Trailer here

And here:-