USA. 1972.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Ralph Bakshi, Based on the Comic Books by Robert Crumb, Producer – Steve Krantz, Photography – Cine Camera (Ted C. Bemiller & Gene Borghi), Music – Ed Bogas & Ray Shanklin. Production Company – Fritz Productions/Steve Krantz Productions.

Voices

Skip Hinnant (Fritz the Cat), Rosetta LeNoire, John McCurry, Phil Seuling

Plot

A young cat Fritz wanders through New York City. He engages in an orgy with three girls at a hippie pad but the police break in and beat everybody up. Fritz flees, thinking he is a wanted by the law. During his flight, Fritz inspires a race riot in Harlem; travels to the West Coast with a woman who wants to settle down with him – only for their car to break down in the desert; and falls in with a group of Nazi biker revolutionaries who want him to blow up a power plant.

Fritz the Cat was a celebrated underground comic-strip from Robert Crumb. Crumb created Fritz in 1959, drawing a series of absurdist comic adventures based on his own cat. The strips initially appeared in 1965 in Help! magazine and in Cavalier magazine from 1968 where they gained a following for Crumb’s bizarre sense of humour and frequently adult content. It is said that the perpetually womanising Fritz and his outrageous adventures through 1960s counter-culture was an alter ego for Crumb who felt he was having little success with women.

Robert Crumb’s cartoons were adapted into this film from then novice animator Ralph Bakshi. Bakshi had begun working in the early 1960s at Terrytoons on shows such as Heckle and Jeckle (1960-6), Deputy Dawg (1962-3) and Spiderman (1967-70). Bakshi disliked the production line process and desired to branch out on his own, he in particular wanting to create a work that embraced the turbulent political upheavals of the 1960s. He then discovered a collected set of Crumb’s Fritz the Cat strips and set about making the film.

The idea of an adult animated film was rejected by every studio in town. Funding was finally obtained from Warner Brothers who promptly sought to dump the project when they became aware of its adult content, requiring Bakshi to obtain further financing from exploitation producer Jerry Gross. Robert Crumb disapproved of the finished film, claiming that the filmmakers had obtained the rights from his former wife when negotiations reached a sticking point. Crumb even wrote a strip satirising Fritz’s success as a film star and finished the strip after the film came out. Despite all of this, Fritz the Cat succeeded in becoming a modest worldwide hit.

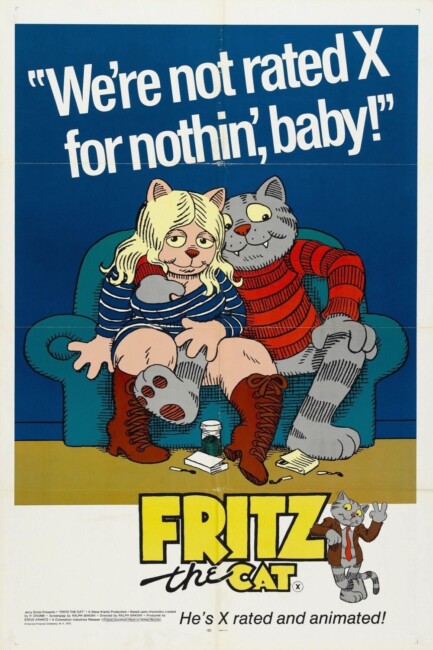

When it came out, Fritz the Cat attained considerable notoriety for being the first X-rated cartoon – there seemed a mental block back in that day that cartoons could only come in the Disney mold and should not be for adults. (It has only marginally changed since – at least in the US mainstream). The film ended up being banned in a number of countries (including in New Zealand until the 1980s).

Fritz the Cat is very much a product of its times. Fritz is a Candide figure – an open-minded innocent who always thinks the best of all he sees as he takes a strung-out picaresque through various facets of the culture of the era. The film pokes snide political jokes at issues of the day – racial tensions, the Arab-Israeli war of 1967. Fritz talks to a Black crow about the Black Power movement – “Why does James Earl Jones always have to do these Black roles?” There is a venture into Harlem, which is inhabited by crows, where a dope-smoking Fritz inspires a race riot and then enters a synagogue filled with Orthodox Jewish beagles – “They all got long hair … Must be a hippie church.” Naturally, the police are caricatured as literally being pigs. The opening credits come against what seems like a conservative radio broadcast with a speaker railing against the decline in modern morality.

Bakshi’s humour is frequently absurdist in keeping with the tone of Crumb’s original strips. Bakshi throws in a number of surreal sequences and bizarre characters, including a psychedelic drug trip sequence that was fairly much mandatory for the era. There is a dog farmer with a corncob pipe that batters a brood of chickens to death in the back of his pickup; a series of nasty scenes where neo-Nazi revolutionaries torture a cow woman prisoner by beating her with chains. There is a heroin-addicted Nazi biker dog who in a wonderfully surreal sequence leaves his girlfriend, rides up a mountainside on his bike before she uses the reflection from her syringe to catch his eye and call him back. There are also a number of songs that spoof the style of both The Beatles and The Beach Boys.

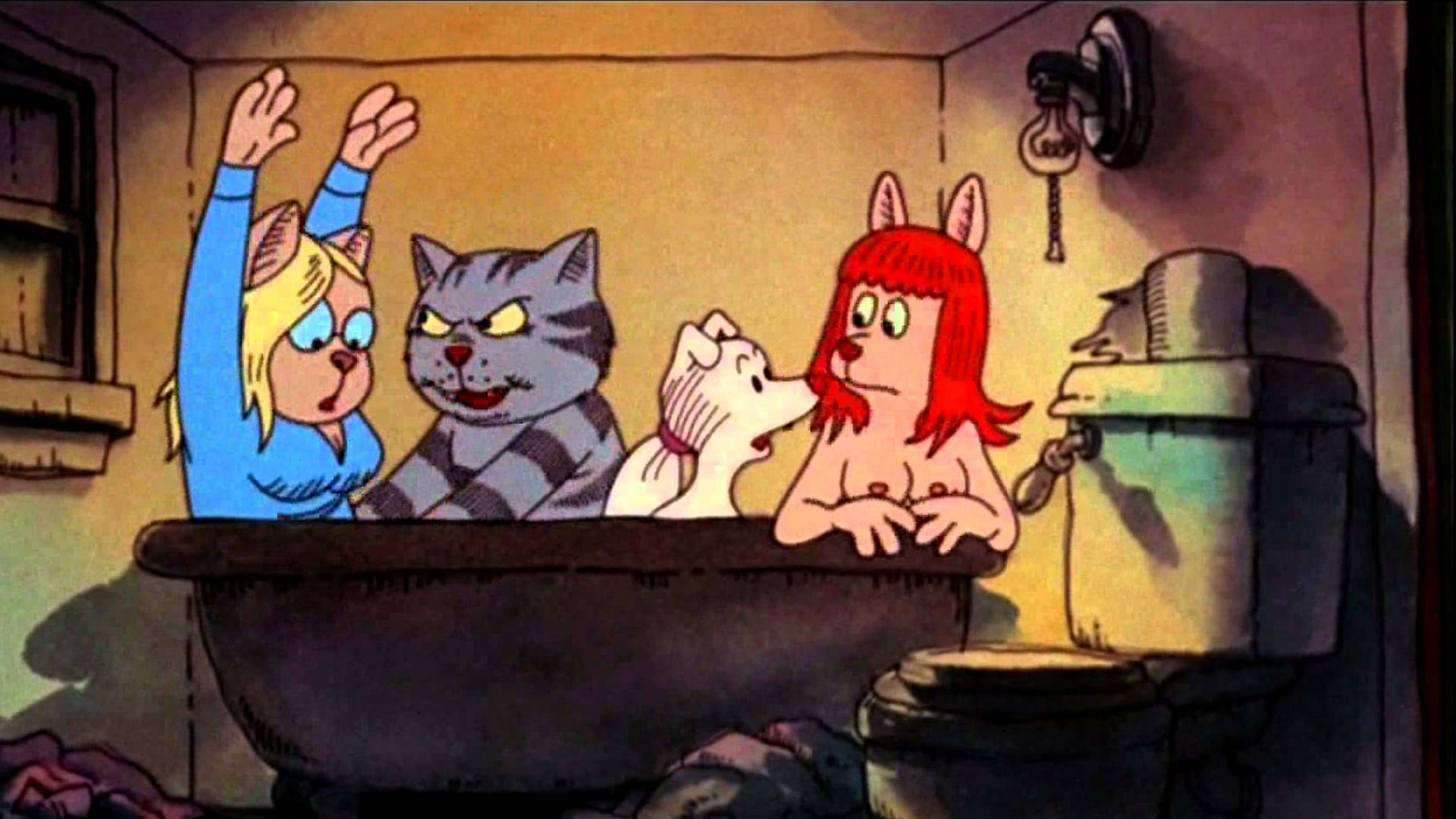

The film is freely and frankly sexual, which was the main point of controversy when it came out. In the first few moments, Fritz persuades three college girls to come back to his apartment for a foursome in the bathtub. Later a stoned Fritz pursues a Black crow woman and starts jumping all over her and having vigorous sex in a junkyard. It is possible that Fritz the Cat is where Furry Fandom and its idea of animals as people’s alter egos and often sexual identities originated. Indeed, Fritz the Cat was likely the inspiration for less than innocent, downright obscene live-action talking animal films to come in later years with Marquis (1989) and Peter Jackson’s Meet the Feebles (1990).

There was a sequel with The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat (1974), made by this film’s producer Steve Krantz, although neither Ralph Bakshi nor Robert Crumb were involved with this. This is regarded as a far less successful film. A portrait of Robert Crumb and his very strange family can be found in the Terry Zwigoff documentary Crumb (1995).

Ralph Bakshi would go on to become a strong name as an independent animator in the next decade making similar adult-oriented, counter-culture works such as Heavy Traffic (1973) and Coonskin (1975); several ventures into fantasy with Wizards (1977), The Lord of the Rings (1978) and Fire and Ice (1983); attempts to address American culture in American Pop (1981) and Hey Good Lookin’ (1982); and the animation/live-action toon film Cool World (1992), before making a return to television and retiring from the late 1990s onwards.

Trailer here