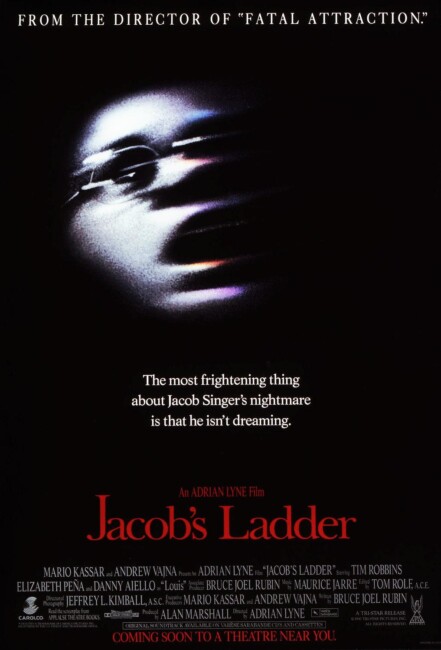

USA. 1990.

Crew

Director – Adrian Lyne, Screenplay – Bruce Joel Rubin, Producer – Alan Marshall, Photography – Jeffrey L. Kimball, Music – Maurice Jarre, Makeup – Effects Smith (Supervisor – Gordon Smith), Production Design – Brian Morris. Production Company – Carolco.

Cast

Tim Robbins (Jacob Singer), Elizabeth Peña (Jezzie Pipkin), Danny Aiello (Louis Bernardo), Matt Craven (Michael Newman), Patricia Kalember (Sarah), Eriq La Salle (Frank), Jason Alexander (Geary), Pruitt Taylor Vince (Paul), B.J. Donaldson (Gabe Singer)

Plot

Postal employee Jacob Singer begins to experience terrifying visions of demonic figures. Contacted by his former Vietnam War comrades, he uncovers evidence that their unit was secretly experimented on by the military with an hallucinogen that turns people into crazed killers and that the hallucinations they are all experiencing could be the result of that. At the same time, Jacob also cannot be sure if his hallucinations are also visions as he lies dying, of figures from the afterlife either come to tear his soul apart or compel him to leave behind the past and die in peace.

Screenwriter Bruce Joel Rubin specialises in visions of the afterlife. Rubin also wrote Ghost (1990), the hugely successful crowd-pleasing afterlife hit that came out the same year as this; and also turned in the script for Brainstorm (1983), an interesting film about exploring the afterlife using Virtual Reality gear; Deep Impact (1998), which could be seen as being about the whole world suddenly confronting its mortality; as well as wrote and directed the non-fantastic My Life (1993) about a man coming to terms with a terminal illness. Rubin has also written scripts for Deadly Friend (1986), Stuart Little 2 (2002), The Last Mimzy (2007) and The Time Traveler’s Wife (2009).

The script for Jacob’s Ladder was in circulation for some ten years and was at one point named one of the Top 10 unfilmed scripts in Hollywood. After passing through the hands of several directors, t was finally greenlit in 1990, amid a host of films that attempted to seriously delve into afterlife issues, which also included Rubin’s aforementioned Ghost and Joel Schumacher’s conceptually underwhelming Flatliners (1990).

In the director’s chair of Jacob’s Ladder was Adrian Lyne. In the mid-80s, Adrian Lyne established himself as possibly the most visually exciting of all new directors with the stunning Flashdance (1983) and 9½ Weeks (1986), films which, their thin plots aside, are visually afire with sensuality, vibrant painterly visuals and an extraordinary depth of chiaroscuro lighting. Following these, Adrian Lyne made the sensation that was Fatal Attraction (1987), a female stalker film that polarised audiences between loving it or finding its politics distasteful. It was with Fatal Attraction that Adrian Lyne’s weaknesses as a director began to become apparent – as someone who has an extraordinary command of the image yet who appears disinterested in story and the wider implications it holds. Lyne’s next film was Jacob’s Ladder, which met with very mixed response due to audience confusions. Lyne then went onto other films such as Indecent Proposal (1993), Lolita (1997) and Unfaithful (2002). Alas, these begin to cut back on the visuals that were his strength, leaving only so-so stories and Lyne’s conservative notions of family underneath.

With Jacob’s Ladder, Bruce Joel Rubin was clearly attempting to conduct a variation on Ambrose Bierce’s famous short story An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge (1891) – for which see the film version An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge (1961). In An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, a Civil War soldier is about to be hanged, only for the rope to snap, allowing him to flee. Just as the soldier returns home to his wife, his neck snaps, revealing everything to be a fantasy that occurred in the moments before his death.

The basic idea of the Bierce story and its twist ending, what this author has termed the deathdream fantasy, has influenced a number of films – Carnival of Souls (1962), Seizure (1974), The Survivor (1981), Sole Survivor (1983), Siesta (1987), Final Approach (1991), A Pure Formality (1994), The Brown Bunny (2003), Dead End (2003), I Pass for Human (2004), Hidden (2005), Reeker (2005), Stay (2005), The Escapist (2008), Passengers (2008), The Haunting of Winchester House (2009), Someone’s Knocking at the Door (2009), The Last Seven (2010), Wound (2010), Jack the Reaper (2011), A Fish (2012), Leones (2012), 7500 (2014), The Abandoned/The Confines (2015), Shadow People (2016) and Alone (2017), plus the finale of tv’s Lost (2004-10) and of course The Sixth Sense (1999). Jacob’s Ladder is essentially the An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge deathdream grafted onto the mid-1980s fad for Vietnam War excoriation dramas post-Platoon (1986).

Bruce Joel Rubin’s original script for Jacob’s Ladder was apparently ripe in Christian imagery, filled with manifestations of full-fledged demons, angels and a vision of the apocalypse. It appears that in Adrian Lyne’s hand, the script has been ecumenicised and the imagery considerably distilled, grounded in something more earthbound. In fact, Lyne seems more interested in the red herring subplot about haunted Vietnam Vets than the afterlife element – the so-called demons are glimpsed all too rarely and the angels not at all except for an ambiguous child guiding Tim Robbins up a set of stairs at the end.

At least, the brief visions of devils have some impact – particularly the recurring vision of a creature with a rotating head, and the strobe-lit appearance of an H.R. Giger-lookalike monster at a party fetishistically clawing Elizabeth Peña’s backside and legs as she seductively writhes and then pops a giant white horn out of her mouth. Or the scene where Tim Robbins is taken into a hospital tied to a gurney where the deeper he travels the more the place becomes filled with mad people and then blood and body parts strewn over the floor.

The singularly most beautiful moment in Jacob’s Ladder, something that almost justifies the rest of its confused script, is Bruce Joel Rubin’s stunningly humanistic vision of afterlife mythology that Danny Aiello momentarily paints, saying that to enter into the afterlife we must give up our past lives – if we hold onto our life then we see demons coming to tear it apart, but if we surrender then we see the demons as angels coming to guide us into the hereafter. The exquisite trompe l’oeil imagery is almost something that a Milton might have conceived were he a humanist.

However, the rest of plot is a jumbled mess. Consider: if all of the film is Jacob’s fighting over and then surrendering his life so that he can die in Vietnam, then why is the bulk of the film set in the present day? (Even more ridiculous is the notion that a present-day Tim Robbins could be a Vietnam veteran – Robbins was 32 when Jacob’s Ladder was made, the mentioned date of 1971 would leave him thirteen years old during the supposed combat scenes). Why does the film bother constructing the principal relationship with Elizabeth Peña for him when the story is about his surrendering memories of hardly-glimpsed wife Patricia Kalember?

The running subplot about the experiments with The Ladder drug proves a complete red herring, something that only frustrates the story intensely. It is a measure of the film’s confusion that it has an ending that dismisses the Ladder drug subplot as a red herring but then straight-facedly goes on to place a sober comment before the end credits run that the hallucinogenic BZ was used on soldiers in Vietnam, although the military deny such. If nothing else this might count as the first film made about Vietnam flash-forwards.

Lyne and Bruce Joel Rubin litter the film with dreadfully portentous, meaning-laden dialogue and images – Tim Robbins sits on a train reading Albert Camus’s The Stranger (1946); an anti-drug campaign ad on the subway reads “Hell” in stark red letters; Jake makes the idle comments about how he sold his soul for a good lay with Jezzie. There are lines like “You look like an angel, Louis” as Danny Aiello stands backlit by the halo from a lamp; while everybody in the film has Biblical names – Jacob, Jezzie (or Jezebel), Gabriel and Eli. If nothing else, you have to commend Bruce Joel Rubin’s academicism – there are few other writers who would throw in reference to the 14th Century Christian mystic Meister Eckhart.

It is also amusing to view Jacob’s Ladder in retrospect and see the picture of the son that Tim Robbins is crying over is none other than the nauseatingly cute Macaulay Culkin of Home Alone (1990) fame.

Jacob’s Ladder (2019) was a remake.

Trailer here