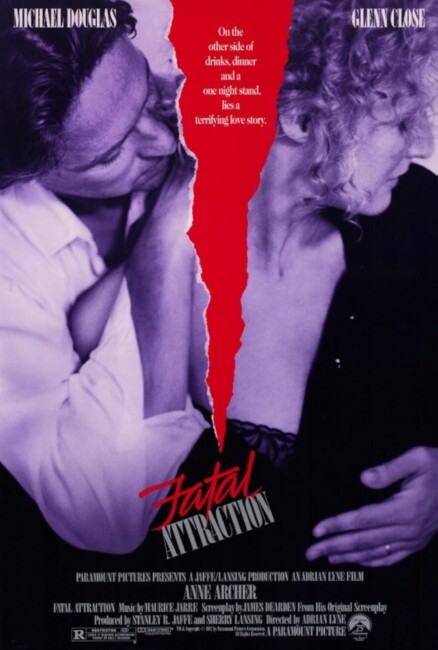

USA. 1987.

Crew

Director – Adrian Lyne, Screenplay – James Dearden, Producers – Stanley R. Jaffe & Sherry Lansing, Photography – Howard Atherton, Music – Maurice Jarre, Makeup Effects – John Caglione & Doug Drexler, Production Design – Mel Bourne. Production Company – Jaffe-Lansing.

Cast

Michael Douglas (Dan Gallagher), Glenn Close (Alex Forrest), Anne Archer (Beth Gallagher), Ellen Hamilton Latzen (Ellen Gallagher)

Plot

While his wife and daughter are out of town for the weekend, lawyer Dan Gallagher dines with client Alex Forrest and they end up in bed together. He leaves her at the end of the weekend with the understanding that it is the end of the affair but instead she slashes her wrists as he opens the door. He takes her to the emergency room and she afterwards apologizes. However, she continues to call and follow him. Finally, she announces that she is pregnant. When he tells her that what she does with the pregnancy is her own choice, she becomes unbalanced, resorting to vandalism, the slaughter of his daughter’s pet rabbit and then the kidnap of his daughter.

Adrian Lyne is a director who makes films for the pure beauty of staging visuals. Lyne’s Flashdance (1983) and 9½ Weeks (1986) are two of the most exquisitely stylish films ever made – they shout out with the sheer sensual pleasure of light, colour and editing. The detail, the quiet and the immaculate chiaroscuros of light and colour that can be found in Adrian Lyne’s films are almost the equivalent of a Constable or a Rembrandt painting made with moving images. Whatever one can say about the slimness of the stories of either Flashdance or 9½ Weeks, they are exquisitely sensual and visual films.

It is the same with Fatal Attraction. The film is almost worth watching alone for the tiny little vignettes of background detail as Lyne’s camera cruises through a room. Alas, Adrian Lyne’s subsequent works – films like Jacob’s Ladder (1990) and Indecent Proposal (1993) – taper off in terms of such visual detail and are more bland. Unfortunately, these latter films clearly show Lyne out of his element. Having cut back on the stylish visuals, he is forced to rely upon the storytelling, and, as Fatal Attraction reveals, Adrian Lyne is not a storyteller, nor has the pacing a thriller needs. Adrian Lyne’s films are cinematographer’s films.

Adrian Lyne’s 9½ Weeks opened up a revolution in screen sexuality. It brought to prominence co-writer Zalman King and his brand of beautifully photographed, high-class erotica – see the likes of tv’s Red Shoe Diaries (1992-7) and films like Wild Orchid (1990) and Lake Consequence (1993) – and paved the way for the later likes of Basic Instinct (1992).

For all that, 9½ Weeks is a conservative film. Though it celebrates the joys of all sensual possibilities, it ends with Kim Basinger deciding that enough is enough and walking away from a purely sexual relationship. A similar sense of conservatism underlies Adrian Lyne’s later films such as Indecent Proposal (1993) and Unfaithful (2002) – the sense that for all the rapturous sensuality that one might find to explore, the welcoming hearth of a traditional marriage and family life represents the best of all possible worlds. Fatal Attraction reinforces this to even greater extremes.

Fatal Attraction was a massive hit and a cause celebre in 1987. It was even nominated for an Academy Award Best Picture, along with Adrian Lyne for Best Director and Glenn Close for Best Actress. The film polarized both sides of the political spectrum, seen as holding all manner of metaphors and statements about AIDS, modern marriage and the male kickback against feminism. This was something that Lyne, who insists he only wanted to make a thriller, laughed at.

If Lyne is laughing though, it is sad for all that is left is a thriller with an incredibly misogynistic attitude towards Glenn Close in its complete lack of sympathy for the use and then discarding of her as a sex object and in the ensuing condemnation of her for choosing not to abort her pregnancy. For all Adrian Lyne’s denial of any message, Fatal Attraction is a film that holds an aggressively, almost vindictively nasty, male response to feminism – the sense that if a woman wants to have the right to say “it’s my body, it’s my choice” then when a pregnancy does emerge it is also a case of “you wanted the choice, you deal with it.

I find Glenn Close one of the coldest and most closed-off actresses around. I am unable to understand why people thought her performance here was so brilliant. All she seems here is clingy, mercurial and psychotic. As a character, she is only defined in terms of how she functions as an antagonist in relation to hero Michael Douglas, never in terms of psychological motivation. Indeed, Alex is given almost no character description and certainly no motivation beyond that of Evil Psycho Bitch.

In contrast to her, the family scenes in Michael Douglas’s home are shot in nostalgic golden hues and a sumptuous warmth – Adrian Lyne even includes a scene of Glenn Close looking in through the window and throwing up at the purity of it all.

Fatal Attraction is an entirely male-oriented film – it is a male fantasy about a man who is lead by his dick, strays from the path of marital fidelity and the nuclear family norm, pays for it by unleashing dire consequences, learns his lesson, dispatches the evilly deranged temptress and restores the cosy status quo of his family life with nary a peep from his forgiving wife, having learned the clear conservative lesson that straying from the path of marriage is a really bad thing. It is a male-oriented fantasy wherein the hurt feelings of the wife are easily washed away and the feelings and responses of Glenn Close at being used and abandoned pregnant are relegated to the realms of the deranged.

Clint Eastwood had conducted the basic set-up of the female stalker before and far better with Play Misty for Me (1971). Adrian Lyne’s failing as a director here is to never let the suspense pay off in a big way. There is certainly one good shock with the revelation of the rabbit in the pot, which Lyne skilfully leads up to with a textbook case of dramatic underscoring – first showing us the boiling pot, then cutting to the child running towards the rabbit hatch, building up a sense of dread before showing us anything.

However, Fatal Attraction needed more of that. The ending generates an okay intensivity but is marred by a schlocky return from the dead cliche. The dvd releases of the film has the original ending where Glenn Close is merely carted away in handcuffs by the police, which shows how little Adrian Lyne was interested in the suspense. Preview audiences had such a reaction to the way that the film had built Glenn Close up as an Evil Psycho Bitch that Lyne went back and shot a new ending where Michael Douglas gets vengeance and stabs her to death. For a far more disturbed variant on the female stalker film, see the amazing French film Anna M. (2007).

The film later remade as the tv mini-series Fatal Attraction (2023) with Joshua Jackson and Lizzy Caplan taking over the Michael Douglas and Glenn Close roles.

The success of Fatal Attraction opened up a host of films wherein usually middle-class men found themselves and their perfect family lives at siege from forces outside – from female stalkers in other copycat films such as the Australian Strangers (1990), Praying Mantis (1993), the Hong Kong erotic film Quenchless Desire (1993), Malicious (1995), The Ex (1996), Passionate Revenge/Friend of the Family II (1996), the comedy A Thin Line Between Love and Hate (1996), Devil in the Flesh (1998), A Bold Affair (1998), Illicit Dreams 2 (1998), Swimfan (2002), The Kindness of Strangers (2006) and several for the internet era with Strangers Online (2010) and Like Share Follow (2017), as well as a true-life female stalker film U Be Dead (2009). Far less substantial have been the number featuring a male stalker – Stalked (1994), Asunder (1998), Too Good to Be True (2003), Secret Smile (2005), The Boy Next Door (2015) and Heartthrob (2017). Other variants have included lesbian stalkers – Kate’s Addiction/Circle of Deception (1999); malevolent children – Mikey (1992), The Good Son (1993) and Daddy’s Girl (1996); malevolent babysitters – The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992), The Perfect Nanny (2000) and The Stranger Game (2006); predatory women in the workplace – The Temp (1993), Disclosure (1994) and The Secretary (1995); psychotic estranged wives – Mother’s Boys (1994) and Unforgettable (2017); psychotic estranged children – The Stepdaughter (2000); psychotic tenants – Pacific Heights (1990), Single White Female (1992), Total Stranger/Stranger in My House (1999), The Perfect Tenant (2000) and The Roommate (2011); psychotic sexually assertive minors – Poison Ivy (1992) and The Crush (1993); psychotic daughters’ bad boyfriends – Fear (1996); psychotic swingers – Zebra Lounge (2001); psychotic overly friendly cops – Unlawful Entry (1992); and psychotic surrogate mothers – When the Bough Breaks (2016). Fatal Instinct (1993) was an occasionally amusing spoof.

Trailer here