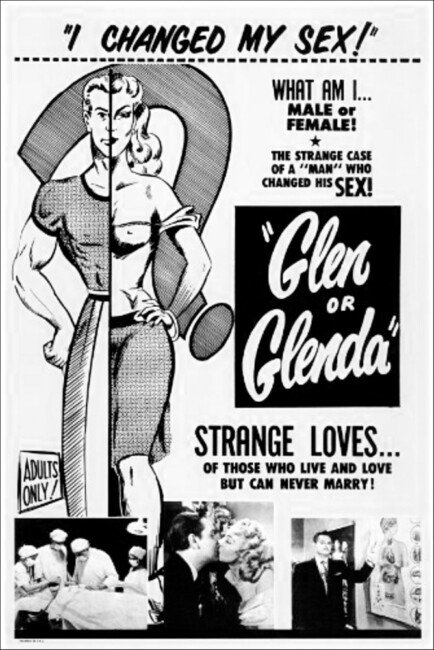

aka He or She; I Changed My Sex; I Led Two Lives; The Transvestite

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Edward D. Wood Jr, Producer – George Weiss, Photography (b&w) – William C. Thompson, Makeup – Harry Thomas. Production Company – Screen Classics.

Cast

Bela Lugosi (The Spirit), Daniel Davis [Edward D. Wood Jr] (Glen/Glenda), Dolores Fuller (Barbara), Timothy Farrell (Dr Alton), Lyle Talbot (Inspector Warren), ‘Tommy’ Haynes (Alan/Ann), Charles Crafts (Johnny)

Plot

Police find a man who has committed suicide while dressed in woman’s clothing and having left a note saying “Let my body rest in death in the things I cannot wear in life.” The investigating detectives visit psychologist Dr Alton who tries to explain what transvestitism is. Alton uses the case histories of two patients – the first is the story of Glen who enjoys dressing in women’s clothing and is tormented over bringing himself to tell his fiancée Barbara; the second is the story of Alan, a ‘pseudo-hermaphrodite’, who even took a suitcase of woman’s clothing with him during service in World War II and eventually had a sex-change operation to turn him into a woman.

Glen or Glenda? is an essential item in the cult of Edward D. Wood Jr, director of the infamous Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959). Glen or Glenda? was Edward D. Wood Jr’s first film as director. As is recounted in Tim Burton’s Ed Wood (1994) biopic, the film began when Wood sought to exploit the topicality of the world’s first sex-change operation with Christine Jorgensen in 1952. The issue of cross-dressing was a deeply personal one for Wood who would often direct films while dressed in angora sweaters and chiffon dresses.

Glen or Glenda? was shuffled around over the years under various titles where nobody quite knew how to handle it. Then came the Medved Brothers’ The Golden Turkey Awards (1980) which, through slamming and ridiculing Wood as the world’s worst director, contrarily ended up deifying his ineptitudes, whereupon Glen or Glenda? was excavated as an essential item in the Edward D. Wood Jr hagiography.

Any Edward D. Wood Jr film has a bizarreness that verges on surrealism. The hilarity here begins from the opening statement that announces with bombastic portentousness: “You are Society. Judge Ye Not.” There is the genre’s saddest failure, Bela Lugosi, by this time well on the way to the dregs of his career and in the first of his collaborations with Wood, delivering his role entirely from an armchair surrounded by an array of tatty skeletons and tribal masks, while playing to the camera with an amazingly wily-faced series of muggings.

The asides that Lugosi makes are truly bizarre – looking down on a split screen of a street scene, he contemptuously spits: “People! All going somewhere. All with their own thoughts, their own personalities. One is wrong because he does it right, one is right because he does wrong [Huh!]. Pull the strings! Dance to that which one was created for!” Later he sits, superimposed over footage of rampaging buffalo, excitedly thumping his fist: “Pull the strings, pull the strink. A mistake is made.” His comment on Daniel Davis/Wood’s decaying mental condition and fevre dream is the entirely incomprehensible: “Bevare! Bevare of the big green dragon that sits on your doorstep. He eats little boys – puppy dog tails – big fat snails. Bevare! Bevare! Take care!”

The great joys of Edward D. Wood Jr’s films are always his pretensions – the overwrought prose and the laughable, wholly unrelated philosophical observations. To the footage of cars driving along a highway, psychologist Timothy Farrell notes: “The world is a strange place to live in – all those cars, all going someplace. All carrying humans which are carrying out their lives.” And there is Wood’s overwrought use of adjectives, with phrases like: “Only the infinity of the depths of a man’s mind can appreciate this story,” or “on their nightly visit to Morpheus, god of sleep,” (meaning ‘when they go to sleep’) or “Now the time is getting very close to the man with the book” (ie. it is getting near to their marriage nuptials).

By far the greatest enjoyment comes when Wood suddenly drops any attempt to pose Glen or Glenda? as a documentary and starts making hilariously spurious appeals direct to the audience. “Give this man satin undies, a dress and he’s the happiest individual in the world. He can think better, he can play better. And he can be more of a credit to his community and his government because he is happy.” Later Wood makes the claim that men’s clothing is designed for work and is too coarse to provide comfort, therefore men are better off wearing women’s clothing. Or how “advertising tells us that seven out of every ten American men wear hats, seven out of ten American men are also bald,” which shows that hats cut off circulation creating baldness therefore men are better off wearing more comfortable women’s hats.

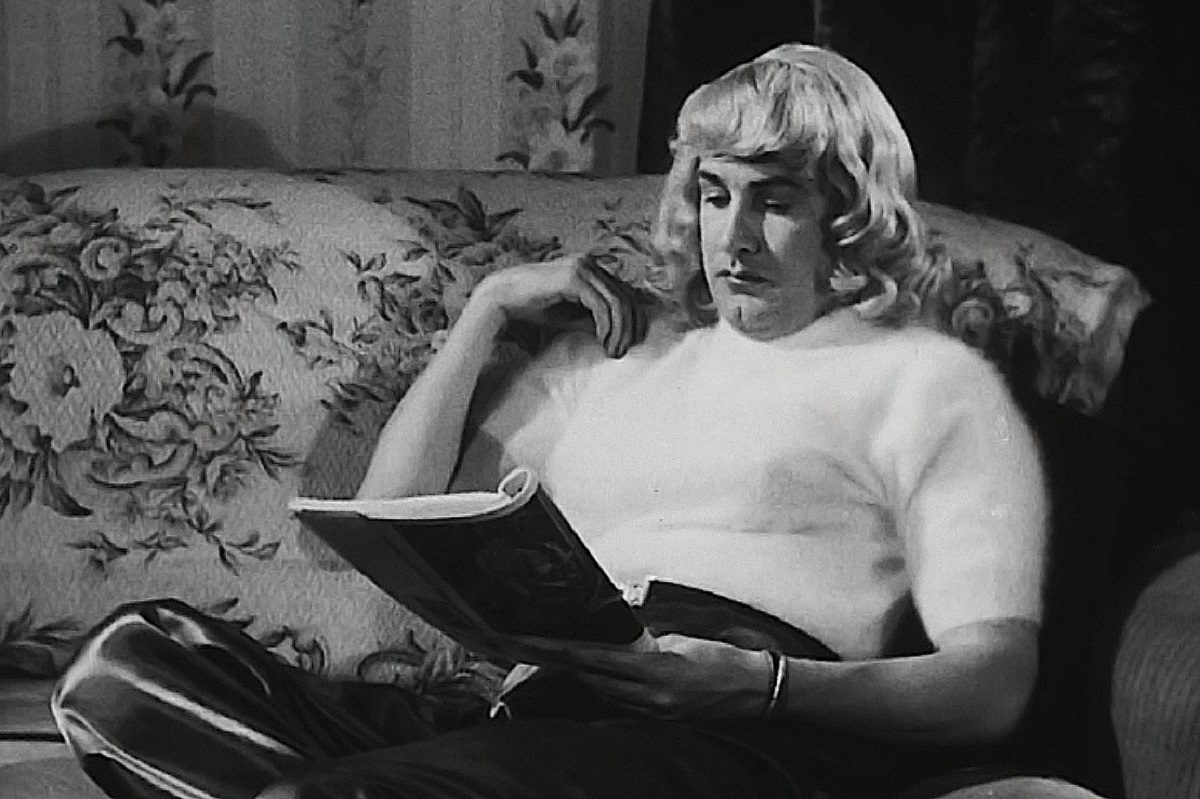

We get scenes of a traffic light repairman and are told he wears woman’s undies and then pictures of a postman doing the dusting in a dress. The lunacy goes on – Wood stages a fevre dream with a smiling Devil looking over his and Dolores Fuller’s wedding, scenes that were perverse for their time in their images of women in scantily clad clothing and underwear whipping and tying each other up.

This is Edward D. Wood Jr in his gushingly inept way making a sincere effort to discuss transvestitism. For all its incompetence and the hilarity of its arguments in favour of cross-dressing, Glen or Glenda? is something that should be appreciated for its attempts to deal with a serious subject decades before it was ever a free topic of discussion. Most of all, Glen or Glenda? is Edward D. Wood Jr’s own autobiography – he was well-known for his own cross-dressing and, like the character of Alan, made the claim that he went into WWII combat wearing women’s underwear under his uniform.

Here Wood plays the role of the transvestite Glen and casts his own wife Dolores Fuller, of blankly inept almost rote-like delivery, as the fiancé Glen is trying to get to understand his problem. Furthermore, Wood’s father, Edward Wood Sr, is uncreditedly cast as the persecuting Devil and is pointedly cut in as Glen’s father when it is mentioned that Glen suffered from a father who wanted to him be a football or baseball star and was tough on him. There is something to Dolores Fuller’s response to Wood/Davis’s explaining his crossdressing problem, “I don’t know, Glen, but perhaps we can work it out together,” that, for all its bad acting and inadequacies, holds a sincere yearning for acceptance that is far more genuine than all the crossdressing comedies like Some Like It Hot (1959), Tootsie (1982) and Victor/Victoria (1982) put together.

Edward D. Wood Jr’s other genre films are:– the mad scientist film Bride of the Monster (1955); the script for the ape-human love saga The Bride and the Beast (1958); Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959); the haunted house effort Night of the Ghouls (1960, released 1983); the script for the nudie horror Orgy of the Dead (1965); the script for the prehistoric xex comedy One Million AC/DC (1969); and the pornographic film Necromania: A Tale of Weird Love (1971).

Full film available online here:-