Italy/France/West Germany. 1969.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Pier Paolo Pasolini, Producer – Franco Rosselini, Photography – Ennio Guarnieri, Production Design – Date Ferretti. Production Company – San Marco S.p.A./Les Film Number One/Janus Films und Fernsehen.

Cast

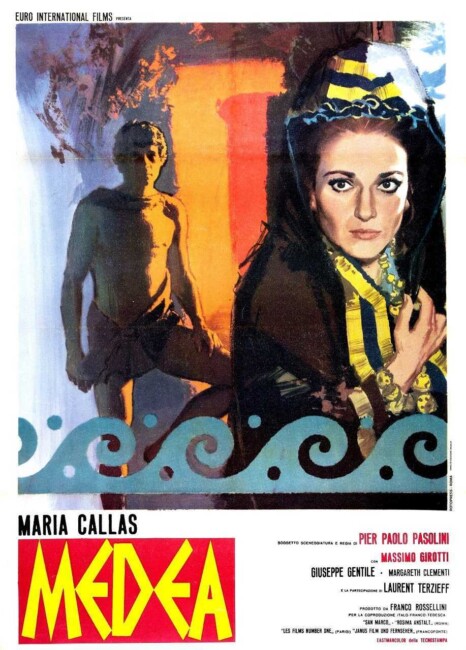

Maria Callas (Medea), Giuseppe Gentile (Jason), Massimo Girotti (King Kresus), Paul Jabara (King Pelias), Margareth Clementi (Glauce), Laurent Terzieff (Centaur), Gerard Weiss (Second Centaur), Anna Maria Chio (Wet Nurse)

Plot

Jason sets out on a quest to find the Golden Fleece for King Pelias. He eventually comes to the land where the fleece is found. The sorceress Medea helps him steal the fleece from the temple and joins the Argonauts as they return home. On the homeward journey, Medea enters Jason’s tent and they become lovers. Back home, they raise several children. However, when Jason announces his marriage to Glauce, the daughter of King Kresus, Medea enacts a horrible revenge.

Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-75) was a controversial figure. In his early years, Pasolini was a published poet, a newspaper editor and novelist, plus an avowed Communist during World War II, before breaking into film as a co-writer on Federico Fellini’s Night of Cabiria (1957). His first film as director was Accatone (1961), which generated controversy due to its portrait of the life of a pimp. Pasolini gained internationally renown for his adaptations of classics, including Oedipus Rex (1967), The Decameron (1971), The Canterbury Tales (1972) and Arabian Nights (1974). He made a number of surrealist genre films (see below) but his most famous work was his last, the taboo-defying film Salo or 120 Days of Sodom (1975). However, this would be his last film and he was murdered by a male prostitute shortly after.

Medea – not to be confused with Tyler Perry’s Madea films – is a character from Greek myth. Descended from the sun god Helios, her importance is in the story of Jason and the Argonauts. The daughter of King Aetes of Colchis, she fell in love with Jason when he came to her land in search of the Golden Fleece where she slaughtered her own brother so the Jason could make an escape. Upon their return, they settled in Colchis and had several children. However, when Jason abandoned her for Glauce, the daughter of King Creon, Medea enacted a horrible revenge, killing their children and Glauce. Medea has gained a classical fascination of her own outside of the Jason story. Euripedes wrote a play Medea (431 BC) and there have been multiple modern retellings, even an opera, based on her story.

Pasolini seemed to have a preference for classical subject matter, providing earthily and often frankly sexual modern versions of the stories. He often took his film crews to exotic locales to film – Medea was shot in Turkey, Syria and various classical locations in Italy, for instance. In many of his classics adaptations, Pasolini had a style that was at odds with mainstream cinema. Contrast Medea with the then most recent other telling of the story of the Argonauts in Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and there is a world of difference between the two films. Jason and the Argonauts is essentially a 1950s Cinemascope spectacular with the highlight of Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion animation sequences and in the story Medea is simply a regular love interest. By contrast, Medea feels like a very naturalistically shot cultural portrait. Pasolini has an almost complete lack of interest in drama and storytelling, let alone special effects. His mise-en-scene is that of drinking in the detail and naturalism of a scene – lots of scenes of peasant ritual, of the Argonauts making camp, the life of the palace and so on.

The upshot of this is that we have a film where we watch things happen but often have no idea why. There is a scene upon their return to Iolcus where Medea is stripped of her robes, although quite what the significance of this is not made clear. We get a scene where they flee in a chariot and Medea stops to hack up a body – unless you are familiar with the original myth, you don’t know that she is killing her brother Absyrtus to delay her pursuing father. In another scene, Medea comes across Jason dancing with a group of others and registers shock but it is not clear from this that he is announcing his engagement to Glauce. For some reason, we also get two different depictions of the death of Glauce at the climax.

This is also a version of the story of Jason that is stripped of much of its magic and delivered as naturalistic pseudo-history – Jason’s obtaining the Golden Fleece comes without any of his traditional fantastical tasks (fighting a dragon, sewing a field with fire-breathing oxen) nor are there any of the creatures they encounter on the journey. We do get a centaur who appears throughout (and in one scene oddly appears alongside a human double in a piece of symbolism that was unclear to me).

On the other hand, there is much that is visually splendid about Medea. The locations look stunning – from the famous fairy chimneys of Cappadocia in Turkey to the Piazza del Miracoli in Pisa and ancient cities of Syria. The costuming looks wonderfully ornate, as though it comes out of authentic cultural ritual rather than the standard Hollywood wardrobe department. And the brutality – where a victim is ritually tied up, strangled and beaten to death before everybody drinks his blood, or flaming bodies falling from the ramparts of an ancient city – has some effect.

In the title role, Pasolini casts American opera singer Maria Callas in her one and only acting role. Callas was 46 at the time. Most of the other versions of the story of Jason and the Argonauts – the 1963 film, the tv mini-series Jason and the Argonauts (2000) – cast her as a standard love interest and fill the role with an actress the same age or younger than Jason. Here however Jason is cast with Giuseppe Gentile, an actor twenty years Callas’s junior (Gentile never appeared on screen again subsequent to this) and is made a fairly peripheral character. Thus the relationship now becomes one of a diva and what is essentially her toyboy.

The Isle of Medea (2017) was documentary about the making of the film.

The Medea story has attracted other filmmakers, including Lars von Trier’s Medea (1988), the Danish-made tv mini-series Medea (2005), and Medea (2019), which updates the story to present-day Chile.

Pasolini’s other films of genre interest include Teorema (1968) about a mysterious visitor; the strange and rather incomprehensible Porcile (1969), one story of which concerns the activities of a cannibal; his beautiful and erotic adaptation of Arabian Nights (1974); and the controversial Marquis de Sade adaptation Salo or 120 Days of Sodom (1975), which was banned in a number of countries.

Trailer here