Canada/France. 2024.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – David Cronenberg, Producers – Saïd Ben Saïd, Martin Katz, Saint Laurent & Anthony Vaccarello, Photography – Douglas Koch, Music – Howard Shore, Visual Effects Supervisor – Peter McAuley, Visual Effects – Compagnie General des Effets Visuels (Supervisor – Guillaume Le Goeuz), Prosthetics – Black Spot FX (Designers – Alexandra Anger & Monica Pavez), Production Design – Carol Spier. Production Company – Saint Laurent Productions/Telefilm Canada/Sphere Films/Crave/CBC Films/Canal+/OCS/Centre National de la Cinematographie et de l’Image Animee/Eurimages/Ontario Creates/SBS/Prospero Pictures.

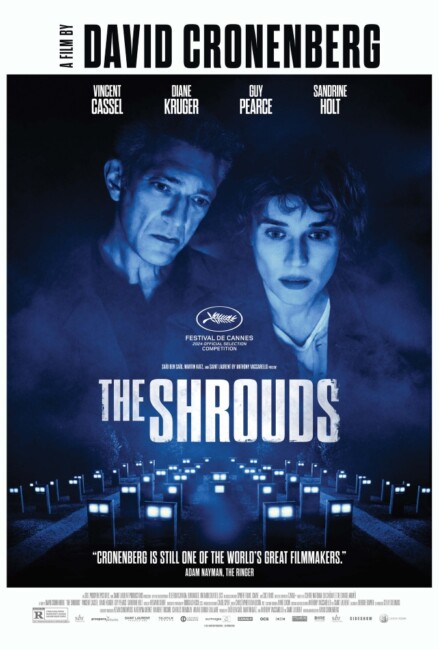

Cast

Vincent Cassel (Karsh Relikh), Diane Kruger (Becca Relikh/Terry Gelernt/Voice of Hunny), Guy Pearce (Maury Entrekin), Sandrine Holt (Soo-Min Szabo), Elizabeth Saunders (Gray Foner), Jeff Yung (Dr. Rory Zhao), Jennifer Dale (Myrna Shovlin), Eric Weinthal (Dr Hofstra)

Plot

Karsh Relikh runs Gravetech, a cemetery that uses a technology he calls Shroudcam where loved ones can log in and view the corpses of the departed as they lie in their coffins. Karsh mourns his late wife Becca who died of cancer. He conceived of Shroudcam as a means to continue to be with her. Now, there is an unexpected break in to the cemetery and several graves are vandalised, before it found that users have been locked out from access to the Shroudcams. Karsh is informed that this may be due to Russian hackers who are seeking to turn the proposed web of Shroudcams around the world into a covert surveillance network.

David Cronenberg probably needs no introduction as the director of a host of genre films that include Crimes of the Future (1970), Shivers/They Came from Within (1975), Rabid (1977), The Brood (1979), Scanners (1981), Videodrome (1983), The Dead Zone (1983), The Fly (1986), Dead Ringers (1988), Crash (1996) and eXistenZ (1999). From around 1990 onwards, Cronenberg turned away from genre material to mainstream works such as Naked Lunch (1991), M. Butterfly (1993), Spider (2002), A History of Violence (2005), Eastern Promises (2007), A Dangerous Method (2011), Cosmopolis (2012) and Maps to the Stars (2014). More recently, he made a return to form with Crimes of the Future (2022), a renaissance of classic Cronenberg themes and one of his finest films. (See below for David Cronenberg’s other films).

Made by Cronenberg at the age of 79, Crimes of the Future is an exceptional work would have been the perfect swansong to a career. Nevertheless, an 81-year-old Cronenberg continues on with The Shrouds and shows no sign of stopping – at the same time as this, he was making acting appearances in Star Trek: Discovery (2017-24) and Ready or Not: Here I Come (2026). Both Crimes of the Future and The Shrouds represent a duology (so far) where Cronenberg has moved beyond the mainstream works that preoccupied him during the late 1990s/2000s and returned to the boundary-pushing explorations of body and sexuality that run through his work of the 1970s and 80s, albeit conducted with a newfound maturity of ideas.

The Shrouds is also Cronenberg at age 81 confronting his own mortality. His wife Carolyn Zeifman died in 2017 so it is not too far of a stretch to imagine the scenes here where Vincent Cassel mourns her loss and talks about ways in which he imagined he could continue to be close to her as being Cronenberg’s own ruminations on his loss. (Although quite what you are meant to make of the ending where Vincent Cassel departs for Hungary because somebody who may have been having an affair with his wife is found to be in the grave beside her that he intended to occupy would be a good guess). Interestingly enough, Cronenberg and his daughter Caitlin made a one-minute short film The Death of David Cronenberg (2021) in which Cronenberg enters a room and finds his own corpse in the bed and lies down beside and cuddles it. We get a not dissimilar reflection of that scene in The Shrouds where Vincent Cassel puts on one of the shroud suits and we very creepily see his own insides being reduced to veins and bones.

The Shrouds is a renaissance of Cronenberg themes. In a good many of his films, Cronenberg feels like some kind of alien anatomist trying to make sense of human sexuality. Some of the most perverse images in any of Cronenberg’s films come here during the flashback scenes with Vincent Cassel in bed as wife Diane Kruger returns from her operation and emerges nude out the shadows to reveal she has had one breast and half of her arm removed. The two converse about whether he still desires her and then proceed to have sex as normal (until interrupted by her hip cracking). This pushing of sexuality way beyond a level that would appeal to anybody except perhaps an acrotomophiliac while observing everything with a coolly detached tone is classic Cronenberg. Elsewhere, Cronenberg includes a scene where Vincent Cassel goes to bed with the blind Sandrine Holt and introduces Diane Kruger as the wife’s twin sister who gets turned on by conspiracy theories.

The casting of Diane Kruger as the wife in the flashback scenes as well as her still living twin sister who Vincent Cassel later gets to take up with, echoes the fascination with Twins that we get in Dead Ringers. Here Cronenberg is constantly making contrast between mirrored selves – of one version of the wife that Vincent Cassel longs to be with decomposing in her grave and another version of her that he goes to bed with; between the wife who has half her body normal, the other half covered by surgery scars and one missing breast and arm ie. one half of her that is alive, the other half on its way to being the decomposing body we see in the grave.

A lot of people just don’t pick up on the vein of drier-than-dry humour that runs through Cronenberg films. When you do get it, it can be quite hilarious. The film opens on Vincent Cassel at the dentist (Eric Weinthal) who delivers the first line in the film “Grief is rotting your teeth” and a few moments later “The teeth do register emotion.” Later during one of the flashbacks Vincent Cassel and wife Diane Kruger have an hilariously deadpan conversation about the surgeon having to remove one of her breasts with wonderfully expressionless lines about whether they will be removing his favourite breast because it is bigger and friendlier.

In the introductory scenes, we see Vincent Cassel on a date with Jennifer Dale – in the restaurant he co-owns located inside the cemetery! – before he takes her on a tour and shows her the grave of his wife where he demonstrates the Shroudcam. There is something to Cassel in these scenes that reminds of the typical Cronenberg scientist who greets the process of transformation with fascination rather than shock – think of Seth Brundle in The Fly or the Mantle twins in Dead Ringers. At the same time as Cassel activates the video and we get the shock image of his wife’s decomposing skeleton in the ground, while he stands there enthusing about apps, 3D rotation and the quality of resolution in the image. We never see date Jennfer Dale again after these two scenes so her response to Cassel is not registered. But this too is typical of Cronenberg where all regular human emotional responses seem to be airbrushed out.

It is after this point that Cronenberg lets the film get weird. There comes the discovery of what may have been monitoring devices implanted inside the wife’s skeleton and then the break-in to the cemetery and the locking off of access to the Shroudcams by what may well be Russian hackers trying to use them to create a covert surveillance network. This propels The Shrouds into a kind of the kind of whackadoodle conspiracy theory territory of writers like Thomas Pynchon or Robert Anton Wilson. Cronenberg keeps compounding this with twists that take everything into the realm of the hilariously bizarre (while also retaining everything perfectly deadpan). Things get really bizarre with revelations that the wife’s surgeon may have been up to no good, including having an affair with her; that the twin sister’s mentally unstable hacker ex (Guy Pearce) may be involved or just as equally have faked injuries he claims come from the Russian mob; or that the Chinese faked everything. Or that none of this is true. The end never leaves us any the clearer.

The Shrouds is nominally an SF film. It seems to take place in an implied Near Future setting – of driverless cars, sophisticated A.I. avatars – but it is also a question of whether you can actually call The Shrouds an SF film. It depicts a very science-fiction-like process – the idea of videocameras inside graves – even though this is something perfectly feasible with existing technologies. Rather it could be said to belong more among the idea of science-fictional states of mind – the erotic obsession with car crashes in Crash, the obsession with mutant gynaecology in Dead Ringers – that runs throughout Cronenberg’s films.

David Cronenberg’s other films are:– Stereo (1969), a little-seen film about psychic powers experiments; Crimes of the Future (1970) set a future where people have become sterile and developed strange mutations; Shivers/They Came from Within (1975) about sexual fetish inducing parasites; Rabid (1977) about a vampiric skin graft; The Brood (1979) about experimental psycho-therapies; Fast Company (1979), a non-genre film about car racing; Scanners (1981), a film about psychic powers; Videodrome (1983) about reality-manipulating tv; The Dead Zone (1983), his adaptation of the Stephen King novel about precognition; The Fly (1986), his remake of the 1950s film; Dead Ringers (1988) about two disturbed twin gynaecologists; Naked Lunch (1991), his surreal adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ drug-hazed counter-culture novel; M. Butterfly (1993), a non-genre film about a Chinese spy who posed as a woman to seduce a British diplomat; Crash (1996), Cronenberg’s adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s novel about the eroticism of car crashes; eXistenZ (1999), a disappointing film about Virtual Reality; Spider (2002), a subjective film takes place inside the mind of a mentally ill man; the thriller A History of Violence (2005) about an assassin hiding from his past life; Eastern Promises (2007) about the Russian Mafia; ; A Dangerous Method (2011) about the early years of psychotherapy; Cosmopolis (2012), a surreal vision of near-future economic collapse; the dark Hollywood film Maps to the Stars (2014); and Crimes of the Future (2022) set in a future world of surgical performance art. Cronenberg has also made acting appearances in other people films including as a serial killer psychologist in Clive Barker’s Nightbreed (1990); a hitman in Gus Van Sant’s To Die For (1995); a Mafia head in Blood & Donuts (1995); a member of a hospital board of governors in the medical thriller Extreme Measures (1996); as a gas company exec in Don McKellar’s excellent end of the world drama Last Night (1998); and a priest in the serial killer thriller Resurrection (1999); and a victim in the Friday the 13th film Jason X (2001).

Trailer here