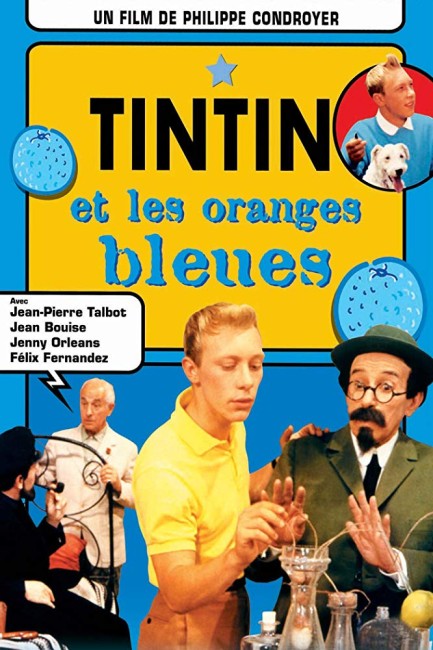

(Tintin et les Oranges Bleu)

France/Belgium/Spain. 1965.

Crew

Director – Philippe Condroyer, Screenplay – Andre Barret, Philippe Condroyer, Remo Forlani & Rene Goscinny, Based on Characters Created by Hergé, Producers – Barret & Robert Laffront, Photography – Jean Badel, Music – Antoine Duhamel. Production Company – Alliance de Production Cinematografique/Procusa/Rodas P.C.

Cast

Jean-Pierre Talbot (Tintin), Jean Bouise (Captain Haddock), Felix Fernandez (Professor Cuthbert Calculus/Tryphon Tournesol), Jenny Orleans (Bianca Castafiore), Max Elloy (Nestor), Angel Alvarez (Professor Zalamea), Andre Mairie (Thompson/Dupont), Franky Francois (Thomson/Dupond)

Plot

Professor Cuthbert Calculus goes on tv, appealing for people to do something about world hunger. Soon afterwards, he receives a parcel from his colleague Professor Zalamea, containing a blue orange that Zalamea claims will be able to grow in the desert and thus solve hunger problems. Calculus, Tintin and Captain Haddock go to Spain to visit Zalamea. However, once there, both Calculus and Zalamea are kidnapped and Tintin and Captain Haddock are forced to go on the trail of international criminals who want to obtain the orange.

Tintin may arguably be the world’s greatest (non-superhero) children’s comic book, indeed was a fondly remembered part of this author’s own childhood. An estimated 100 million copies of the Tintin books have been published worldwide in 58 languages and still sell around three million copies per year 70 years after they were first published. Tintin was the creation of Belgian Georges Remi (1907-83). Remi signed his work as Hergé (after his initials, reversed the French way). Hergé first created Tintin in Le Petit Vingtieme (The Small Twentieth), a children’s supplement to the Catholic newspaper Le Vingtieme Siecle (The Twentieth Century), beginning with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1929). The stories developed an enormous popularity.

Hergé published eight Tintin stories in Le Vingtieme Siecle before publication was interrupted (in mid-story) by the German invasion of Belgium in 1940. The Wartime era caused much in the way of problems for Hergé – he was jailed under the German occupation, and then accepted what has now come to be regarded as a collaborationist position with the Nazis, where he published five-and-a-half other Tintin works in the German-controlled newspaper Le Soir. These often contained propagandist elements – The Shooting Star (1941), for instance, features a greedy Jewish financier as villain – although this era did introduce the series most popular character of Captain Haddock.

The post-War period began to see the publication of the Tintin strips in the book form they are known as today and more importantly in colour. However, dogged by accusations of being a Nazi collaborator, Hergé underwent many personal and health crises and frequently wished he could divorce himself from his creation, even at the same time as he was seeing it become a worldwide success that made him wealthy. Despite, it is during this time that Hergé began to produce his best work – Destination Moon (1953) and Explorers on the Moon (1954) in which Tintin and crew made the first Moon landing; the Cold War thriller The Calculus Affair (1956); the wacky Flight 714 (1968), which tied in the fascination with Erich von Daniken’s Chariots of the Gods; and Tintin in Tibet (1960), which is regarded by most Tintophiles as Hergé’s singular best work.

Tintin was always a creation of Hergé’s background – he grew up in a staunch Catholic family and found a great childhood love of the boyscout tradition. When it comes down to it, Tintin is a fantasy adventure of boyscouthood. Tintin was the perpetual boy-man, caught on a cusp between adolescence and adulthood, never changing his costume from his blue sweater and long baggy shorts. No such thing as romantic entanglement ever assailed the horizon of his perpetual adolescence.

The appeal of the comics was as much Hergé’s ligne claire style (solidly drawn lines) and rigorous research – he would study in great detail the various locations of the stories, incorporated the designs of existing vehicles, and for Destination Moon even built technically-accurate model rocketships – as it was their ability to sweep across globe-spanning locales and conjure a fabulous sense of adventure. Tintin’s various adventures took him to everywhere from the Congo to both North and South America, China, Scotland, the Sahara, Tibet and even The Moon (even though Hergé himself visited none of these places).

And then of course there was the memorable line-up of comedic characters – the recovering alcoholic buffoonery of Captain Haddock and his flamboyantly apoplectic insults, the perpetually hard-of-hearing Professor Calculus, the screeching diva Bianca Castafiore, the bumbling identical detectives Thompson and Thomson.

The strips are surprisingly popular, albeit somewhat jingoistic today. Although in latter years the question of Hergé’s politics has become a question mark that stands over them – even as recently as 1999, the French parliament held a debate on whether Hergé and the strips were to the political right or left. Of much evidence is Tintin in the Congo (1931), which ardently supported French colonialism and featured racist caricatures of African natives, and the anti-Communist diatribe of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. Hergé died of pneumonia in Brussels in 1983, leaving behind 23 Tintin adventures and the uncompleted Tintin and the Alphart.

Tintin has made sporadic appearances on film. Prior to this there had been an earlier live-action Franco-Belgian co-production Tintin and the Mystery of the Golden Fleece (1961), which had also starred Jean-Pierre Talbot. Tintin and the Blue Oranges was the second effort from the same people, although most of the supporting cast have been replaced by new actors. The film bears an amazing degree of likeness to the original strip, even down to a perfect simulation of the character’s costumes and incorporating trivia from the strip like the portrait of the pirate Red Rackham on the wall at Marlinspike Manor. The actors playing Tintin and Haddock are superb mimes – Jean-Pierre Talbot does a marvellous job with the acrobatics and Jean Bouise gets Captain Haddock’s bluster down perfect.

The Europeans always manage to do their comic book adaptations with an ease the Americans miss – they are colourful, uninhibited in their absurdities and directed in virtual comic panels and speech balloons – see the likes of Danger: Diabolik (1967) and Barbarella (1968) – whereas the American equivalents are usually sentimentalised or blown up to posturing heroic proportions, or failing that camped up. Tintin and the Blue Oranges has a perfectly colourful frivolousness, at times even bursts into speeded-up silent film action.

Certainly, there is more of a knockabout slapstick tone to this one and less in the way of globe-spanning adventure that Hergé would have opted for, one suspects. The film’s major problem is a rambling, confusing plot and the need to add a cast of children for kiddie appeal – but the action moves with such fun and energy that it makes up in enthusiasm what it misses elsewhere.

In further on-screen adventures, there were two feature-length animated Tintin films, Tintin and the Temple of the Sun (1969), adapted from the Hergé strip Prisoners of the Sun (1949), and the original story Tintin and the Lake of Sharks (1972). The best adaptations of Tintin came in the Canadian animated series The Adventures of Tintin (1992), which adapted the original strip stories extremely closely, even down to retaining the same comic-strip panels as directorial set-ups, and Steven Spielberg’s animated adaptation The Adventures of Tintin (2011). Tintin and I (2003) is a documentary about the life of Hergé.

Clip from the film here