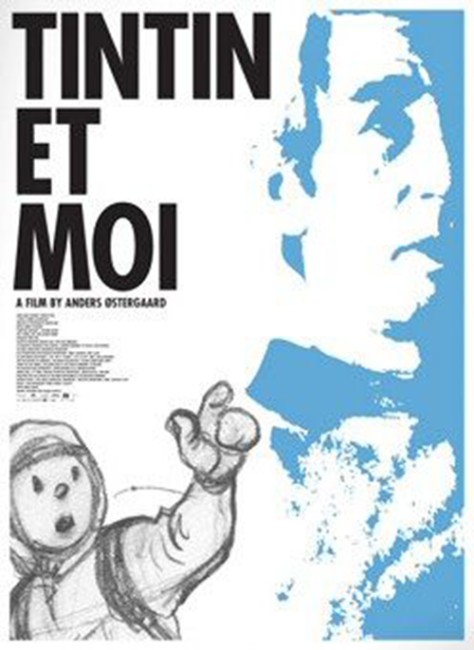

(Tintin et Moi)

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Anders østergaard, Producer – Peter Beck, Photography (some scenes b&w) – Simon Plum, Music – Halfdan E. & Joachim Holbek, Animation Supervisor – Kristen Skytte, Special Effects Supervisor – Christopher Dumoulin. Production Company – Angel Productions/Moulinsart/Periscope Productions/Dune/Leapfrog/RTBF/Avro/France 2/VRT/DR TV/France 5/SVT/YLE-FST/NRK/Suisse Romande.

Cast

Hergé, Numa Sadoul, Michael Farr, Harry Thompson

Tintin and I is a documentary about Georges Remi (1907-93), better known to the world as Hergé, creator of the much-loved comic-book character Tintin. The adventures of Tintin spanned 23 volumes, which were initially printed as a weekly strip in the newspaper Le Vingtieme Siecle beginning in 1929 and later published in a series of books in colour after World War II. The Tintin books have sold millions of copies the world over and are much-loved children’s favourites.

The documentary Tintin and I comes out of a series of tape-recorded interviews that Brazilian-born journalist Numa Sadoul made with Hergé in 1971. Numa Sadoul later published the interviews as a book Entretiens avec Hergé (Discussions with Hergé) (1975). (Hergé insisted the interview transcripts be heavily edited before being first published, however the book has been republished a number of times since in editions that return to the original text of the recordings). Tintin and I presents the original audio recordings made by Numa Sadoul, along with stock footage of Hergé, even a sketchy animated silhouette of Hergé that is lip-synched to the words.

Tintin and I gives a considerable in-depth portrait of Hergé, covering his childhood in the Boy Scouts, the influence of the Catholic Bishop Norbert Wallez who inspired Hergé to create Tintin, Hergé’s controversial period during World War II and his creative struggles in the years after. We get some coverage of Hergé’s life after the recordings were made, including the much-publicised meeting up again with his old friend the Chinese artist Tschang Chong-chen after four decades.

The documentary goes into Hergé’s life in some psychoanalytic detail, including exploring the origin of his art – how the Tintin strips began as a politically motivated strip for youngsters under Bishop Wallez; how the influence of Tschang Chong-chen, initially in an effort to ensure that the The Blue Lotus (1934) did not portray Chinese culture as a Western cliché, led to Hergé’s fascination with accuracy of geographic detail. (The film even shows the near-identical comparisons between some of the locations depicted in the strips and their real-life counterparts).

Tintin and I is at its most fascinating when it is offering speculation and insight into the psychological relationship between the artist and his creation. The most potent piece of insight comes from one of the British scholars who pinpoints how the strips represent Hergé’s view of the world – how Tintin was originally the idealised boy scout wish fulfillment hero but how, with Captain Haddock’s introduction during the War, Captain Haddock soon came to stand in for a middle-aged Hergé wishing the rest of the world would just go away.

The issue that the documentary seems most interested in is Hergé’s nervous breakdown during the late 1950s, which led to his creation of the strip that many regard as his masterpiece Tintin in Tibet (1960). The film is fascinated with the significance of Tintin and Tibet – one of the central panels of Tintin and Captain Haddock trekking past the crashed airplane plays throughout the film a number of times and is even made into a three-dimensional still frame. The film and Hergé himself see a link between the comic’s snow-white setting and the Hergé’s symbolic dreams all in white that were precipitant of a nervous collapse due to the breakdown of Hergé’s marriage to Germaine Kieckens.

The one controversy that continues to dog Hergé is the question of just where his Wartime sympathies lay when he continued to publish Tintin in the Nazi-controlled newspaper Le Soir and whether he was a collaborator or had no choice in the matter. It is not an issue that Tintin and I seems to offer any clear answers to. The film’s sole comment on the issue is the voice of Hergé who explains his actions as akin to the bakers and tram drivers who kept on working and conducting life as normal under the Nazi occupation of Belgium. It is an explanation that seems plausible on the face of it, and indeed, as the film points out, during this time the strips became much more fantastical and Hergé was seen to be trying to avoid the controversy of previous stories like The Blue Lotus, which criticised the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, and King Ottokar’s Sceptre (1938), which was written as a parable of Hitler’s invasion of Austria.

While it seems plausible for Hergé to say that he was just trying to carry on under the occupation like everybody else, one wishes that Tintin and I would have dug a little deeper than that. While the film points out the clear move to fantasy in the comic-strip, on the other hand there were occasions (unmentioned by the film) where Hergé seems to be adopting a pro-actively Nazi line, such as including a racially caricatured Jewish villain in The Shooting Star (1941) or the atrocious carciatures in such Wallez-backed strips as Tintin in the Congo (1931).

Furthermore, Hergé was a longtime protégé of the abbé Norbert Wallez who was known for his ardently right-wing views and support of both Hitler and Mussolini – Hergé married Wallez’s secretary Germaine Kieckens and it was Wallez who actively pushed Hergé to create Tintin as a political mouthpiece to youth. Hergé’s answer to the question of whether he collaborated is not unakin to the answers given by Leni Reifenstahl as to why she made propaganda films for Hitler – that she was just doing a job and was unaware of the political implications. With both Riefenstahl and Hergé, it is in the end a case where one is left believing either that they both had an extraordinary naiveté about the world around them and what others were demanding they say through their work, or simply they were these were answers given by artists in denial. To Hergé’s credit, he did manage to make public denunciations of many of the positions held by Bishop Wallez and his own Wartime involvement in later years. It is however a controversy that continues to hang over Hergé with fascinatingly unanswered ambiguity.

The Tintin stories have appeared on film a number of times. There was a stop-motion animated version of The Crab with the Golden Claws (1947) but this has only had two screenings before the producer was declared bankrupt and fled the country. There were two French-made live-action films Tintin and the Mystery of the Golden Fleece (1961) and Tintin and the Blue Oranges (1965) starring Jean-Pierre Talbot as Tintin; a one-hour Dutch-made animated adaptation of The Calculus Affair (1964); two feature-length animated films Tintin and the Temple of the Sun (1969), adapted from Prisoners of the Sun, and the original story Tintin and the Lake of Sharks (1972); the Canadian-made animated series The Adventures of Tintin (1992), which adapted each episode directly from the original comic-strips extremely closely, even down to retaining the comic-strip panels as directorial set-ups; and Steven Spielberg’s animated film The Adventures of Tintin (2011).

Trailer here