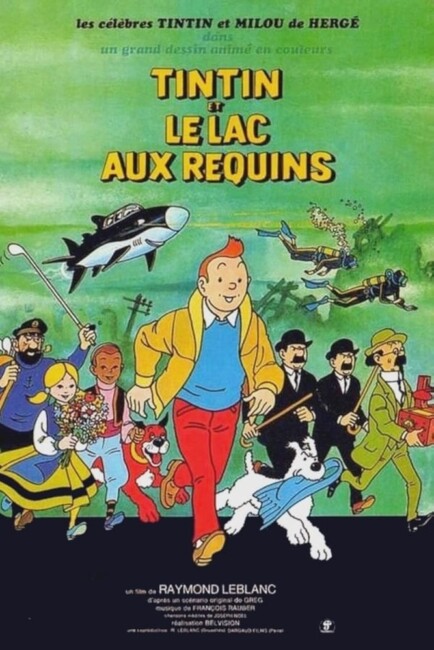

aka The Mystery at Shark Lake

(Tintin et le Lac aux Requins)

Belgium/France. 1972.

Crew

Director – Raymond LeBlanc, Screenplay – Greg, Adaptation – Jean-Michel Charlier, Rainer Goksch, Eddie Lateste & Jos Marissen, Photography – Francois Leonard, Jean Midre & Jean-Marie Urbain, Music – Francois Rauber, Songs – Joseph Noël, Special Effects – Eddie Lateste, Animation Directors – Noella Beeldens, Emmy Boremanns, Jean-Pol Chapelle, Sam Gahide, Danielle Hoebeck, Christianne Michel, Martine Pochet, Christianne Segers & Claudine Vande Winckel, Art Direction – Paulette Melloul. Production Company – Raymond LeBlanc/Dargaud-Films.

Plot

Tintin, Captain Haddock and Snowy fly to meet Professor Calculus in Syldavia, joined along the way by the detectives Thompson and Thomson. However, he pilot bails out in mid-flight, abandoning the plane to crash. They survive when the plane makes a fortuitous crashlanding on a mountainside. They join Professor Calculus where he is working in a villa on the shores of the reputedly cursed Lake Flashijehaf. There Professor Calculus reveals that he has created a device that can perfectly duplicate another object. He is planning to use this to fool those responsible for a recent spate of thefts at art galleries around the world. However, spies working from a base beneath the lake are determined to get their hands on the device. The spies kidnap Nico and Noushka, two local children that Tintin has befriended, and offer their return in exchange for the device. Tintin discovers that the mastermind behind the scheme is his old nemesis Rastapopolous.

Tintin and the Lake of Sharks is based on the much-loved comic book character created by the Belgian artist Hergé (real name Georges Remi). The Tintin adventures concern a perpetually youthful reporter and his faithful sidekicks, the reformed alcoholic sea captain Haddock, the dog Snowy and the perpetually hard of hearing Professor Calculus, and their journeys to various globe-spanning locales. The original Tintin comic-strips first appeared in the Catholic children’s newspaper Le Petit Vingtieme in 1929 and were later published in book form. Following World War II (a controversial period for Hergé), these books began to be published internationally and gained a huge following. There were 23 published Tintin adventures up until Hergé’s death in 1983, as well as the uncompleted, posthumously released Tintin and the Alph-Art (1986).

There have been a number of Tintin screen adaptations – the Franco-Belgian live-action films Tintin and the Mystery of the Golden Fleece (1961) and Tintin and the Blue Oranges (1965), as well as a one-hour animated tv adaptation of The Calculus Affair (1959). The best Tintin screen adaptations were found in the Canadian animated series The Adventures of Tintin (1992), which adapted the original strip stories extremely closely, even down to retaining the comic-strip panels as directorial set-ups. More recently, Steven Spielberg offered the world his animated adaptation The Adventures of Tintin (2011). Also of interest is Tintin and I (2003), a documentary about the life of Hergé.

Belgian director-producer Raymond LeBlanc and the French production company Dargaud Film had also been behind a previous animated adaptation Tintin and the Temple of the Sun (1969), adapted from the Hergé strip Prisoners of the Sun (1949). Dargaud had also produced six animated films based on the other famous Belgian comic-book Asterix, with this film’s director Raymond LeBlanc also producing the first two of these. Raymond LeBlanc was a Belgian resistance fighter against the Nazis during World War II. Following the war, he started Tintin in 1946 and became the book publisher of Tintin.

Of all the various Tintin screen adaptations to date, Tintin and the Lake of Sharks is the one that gets the spirit of the Hergé originals down perfectly on screen. The Adventures of Tintin tv series also did an excellent job but the quality of the animation and at least the visual capturing of the characters is much superior here. Even if Tintin and the Lake of Sharks is a mixed bag elsewhere, Raymond LeBlanc gets the expressions, the roundedness of the characters, Hergé’s love of background detail and sense of humour down just perfectly. There is also great respect paid to the continuity of the strip with recurring characters like Madame Castafiore and the villain Rastapopolous turning up, even an appearance of the miniature submarine used in Red Rackham’s Treasure (1944).

On script, hiding behind the pseudonym Greg, is Michel Regnier, a Hergé associate who was the editor of Tintin magazine and had written the script for Dargaud’s Tintin and the Temple of the Sun at Hergé’s behest. Hergé’s involvement via a proxy may well explain why Tintin and the Lake of Sharks works so well as a screen adaptation of the comic strip. (Hergé also oversaw The Lake of Sharks‘ adaptation into comic-book form).

On the minus side, the English-language version seen here is almost entirely killed by terrible dubbing. Tintin at least comes across exactly as one would imagine him on the page but the worst is Captain Haddock who is dubbed by an uncredited actor with a deep baritone voice and comes out sounding like a Louis Armstrong or a Jackie Gleason but played with a cynically drunk indifference. Such a laidback voicing is completely wrong for the character.

The animation is limited, although the artwork is fine. Raymond LeBlanc’s main failing as a director is that he never pushes the film for much in the way of drama. Action scenes like the crash of the plane on the edge of a mountainside fall somewhat flat, where a modern film would almost certainly have made a much more exciting spectacle out of it.

Raymond LeBlanc’s interest appears to be far more in the slapstick element. Supposedly dramatic scenes are often inappropriately scored with light, jaunty music, for instance. There are a couple of passable scenes during the flooding of Rastapopolous’s base under the lake and especially during the scenes with Captain Haddock in the submersible and the children in a remote-controlled vehicle. Eventually, Raymond LeBlanc’s interest in slapstick overruns the film, with silly scenes like where Thompson and Thomson inadvertently go water-skiing. Especially silly is a supposedly serious climactic fight on the deck of a submarine, which is intercut with scenes of a football announcer making it appear as though he were commenting on the fight.

Also, the plot the film is working with is a slight one – it is noticeable, for instance, that despite the title there are no sharks in the lake, other than the vaguely shark-shaped one-man submersible that Captain Haddock goes investigating in.

Trailer here