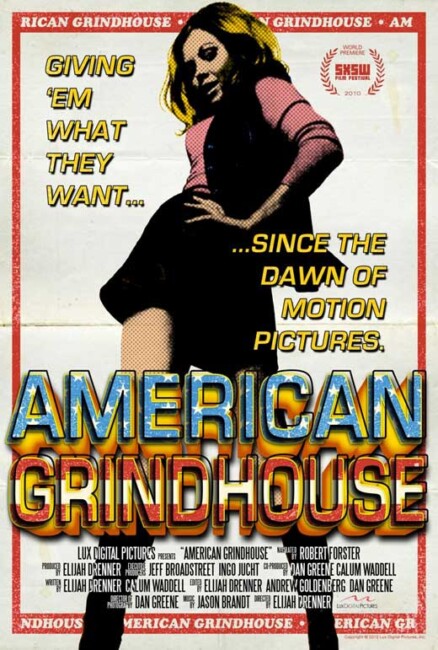

USA. 2010.

Crew

Director/Producer – Elijah Drenner, Screenplay – Elijah Drenner & Callum Waddell, Photography/Additional Music – Dan Greene, Music – Jason Brandt, Animation – Mike Boas & Dan Greene. Production Company – End Films/Lux Digital Pictures.

With

Narrated by Robert Forster. With: Allison Anders, Larry Cohen, Joe Dante, Don Edmonds, David Hess, Jack Hill, Jonathan Kaplan, Jeremy Kasten, John Landis, Herschell Gordon Lewis, William Lustig, Ted V. Mikels, Kim Morgan, Eddie Muller, Fred Olen Ray, Eric Schaefer, Lewis Teague, James Gordon White, Fred Williamson)

American Grindhouse is a documentary about the history of grindhouse theatres – theatres that were designed to show cheap, lurid sensationalistic material that screened around the clock (in other words grinding them out). Well, actually, no. Grindhouse is a colloquial term that (I believe) sprang up in the 1970s and never widely came into use outside of film fan circles. I mean, of all the magazines and books I have collected on genre cinema published pre-2007, I think I have heard the term used less than a dozen times – it was not widespread even in film jargon. It was certainly a term unknown to the public at large were it not for the Quentin Tarantino-Robert Rodriguez film Grindhouse (2007) – see Death Proof (2007) and Planet Terror (2007) – whereupon it suddenly become a piece of populist jargon used to refer to 1960s/70s exploitation cinema. So what we have with American Grindhouse the documentary is not so much a history of these so-called grindhouse theatres but of American exploitation cinema itself.

As such, American Grindhouse does a reasonably good job of charting the history of the exploitation film, delving through such niches as the 1950s monster movie, the teenage genre and beach party film, the nudie (and its cousin ‘the roughie’), the splatter film, Nazi-sploitation, porn and of course the Blaxploitation genre. The best parts, for me at least, were those that sought to find the origins of the exploitation genre. Here some of those who have written books on the subject, Eddie Muller, Kim Morgan and Eric Schaefer, prove particularly insightful.

The genre is traced back to the early days of cinema with works exploiting the fear of white slavery such as Traffic in Souls (1913) – pioneering filmmaker Thomas Edison is even cited as an early exploitation director. There is the insightful claim made that exploitation cinema would never have existed were it not for the Hays Code instituted in 1934 that created a set of moral guidelines for the studios, thus immediately defining a series of taboo topics that independent filmmakers outside the regular theatrical chains began to challenge in interesting ways. One of the topics the film touches on is the popularity during the 1940s of films about sexual health, in particular ones depicting childbirth, and how exploitation filmmakers could get away with an enormous amount while hiding it under the guise of public morality.

The most fascinating argument the documentary offers is that almost all American exploitation cinema can be grouped together as sublimated sexuality – that filmmakers offered up as much titillation as they could get away with in the form of burlesque, bikini films, early nudist films and then nudies – because they were not legally permitted to depict sexuality on the screen. The ‘roughie’, which was a variant on the nudie in the 1960s depicting girls in a state of undress being beaten and tortured, is seen as a direct sublimation for sexual activity. Herschell Gordon Lewis, the godfather of the splatter film, tells how his first splatter film Blood Feast (1963) grew directly out of him making nudies and finding the market becoming such an overcrowded one that he needed to find some new form of sensation.

There are plentiful clips offered from the various films discussed. In fact, American Grindhouse covers so much ground that one suspects a far more in-depth treatment would have been better afforded by something like a ten-part tv series. This does lead to some surprising omissions. We get a history of American International Pictures (AIP), discussion of their monster and beach party films, mention of AIP’s two heads Samuel Z. Arkoff and James H. Nicholson, and, while there are clips shown of his film The Wild Angels (1966), there is oddly no mention made of Roger Corman, perhaps the pre-eminent producer and director of B films.

There is also no mention made of Night of the Living Dead (1968), which took the low-budget exploitation genre to a major success, produced numerous imitators and gave life to the 1970s independent horror film, nor of George A. Romero, one director who made exploitation filmmaking into an artform and gave it a social legitimacy. There is mention made of Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972) and an interview with its star David Hess, but no mention at all of the most famous film in this Vietnam War-influenced shock and brutality genre – The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974).

There are a fair number of people interviewed. What must be said is that some of these have either made dubious contributions to what could be considered grindhouse material or came after the period when the film sees grindhouse as having died – Joe Dante, John Landis, Fred Olen Ray (who is a prolific exploitation director but whose success almost entirely came in the video revolution), Lewis Teague and William Lustig who at least made a couple of grindhouse porn films. Particularly superfluous is the inclusion of Jeremy Kasten, the director who remade Herschell Gordon Lewis’s The Wizard of Gore (2007), and seems barely old enough to have been born when grindhouse cinema was in its heyday. There is a surprisingly scant number of interviews with hands who directly came from the classic grindhouse/exploitation era themselves – Herschell Gordon Lewis, Don Edmonds, Larry Cohen, Ted V. Mikels, Fred Williamson, Jack Hill – all of whom you wish had been granted more screen time.

The film makes an interesting argument for the death of the grindhouse – although not necessarily an argument I agree with. It sees the end of the era as being Jaws (1975), a point where mainstream cinema finally began to start copying exploitation-type films. I don’t know if this necessarily holds water as an argument – there have, for instance, been plenty of examples of mainstream cinema making exploitation-type films before. Indeed, American Grindhouse makes an interesting case at one point for the number of similarities between Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Herschell Gordon Lewis’s Blood Feast and sees the only real difference as being that Psycho was studio released and had a major publicity campaign.

What about the massive success of The Exorcist (1973), a film pitched to shock and outrage appeal far more than Jaws ever was? I don’t think any of these necessarily saw the end of grindhouses – indeed, the successes of Psycho, The Exorcist and Jaws saw a huge number of cheaply made imitators flooding the market, as American Grindhouse sort of acknowledges in its brief coverage of Jaws copies like Joe Dante’s Piranha (1978) and Lewis Teague’s Alligator (1980).

My feeling, and one that is never voiced by American Grindhouse, is that what killed the grindhouse theatre was the VCR and videotape revolution in the 1980s (and later the rise of cable tv) where films suddenly became ones that you could watch in your own home rather than in a seedy neighbourhood movie theatre, where you could go to a commercial library and rent the material you wanted rather than be subject to whatever the theatrical distributors at the local grindhouse decided to screen that week.

Director Elijah Drenner has made some 200 short films for dvd releases of exploitation and genre classics, many of which are discussed here, and produced nearly that same number again. His one other full-length documentary was That Guy Dick Miller (2014) about B movie actor Dick Miller.

Trailer here