Crew

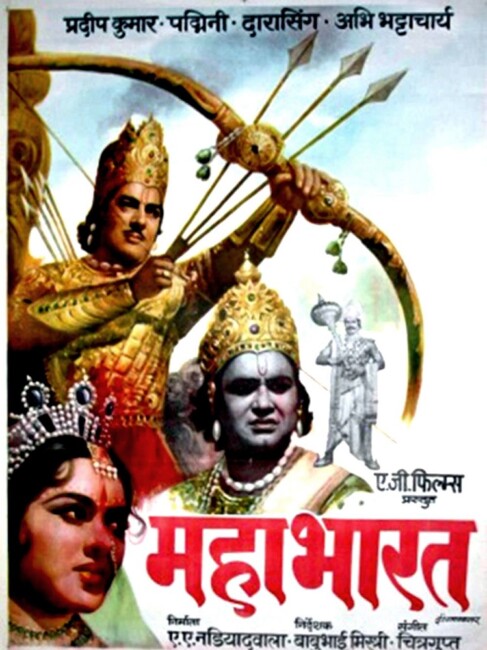

Director/Special Effects – Babubhai Mistry, Screenplay – Pt. Madhur & Vishwanath Pande, Story – Ramash Vaidya & Narotam Vyas, Dialogue – Madhur & C.K. Mast, Producer – A.A. Nadjadwala, Photography – Narendra Mistry & Peter Parreira, Music – Chitsagupta, Songs – Bharat Vyas, Optical Effects – Dahayabhai & Gordhambhai, Makeup – Sawant Abdulrahim, Art Direction – A.A. Majid, Dance Choreography – Suresh. Production Company – A.G. Films.

Cast

Abhi Bhattacharya (Lord Krishna), Pradeep Kumar (Arjun), Padmini (Draupadi), Dara Singh (Bhim), Jeevan (Mama Shakuni)

Plot

The throne of Hastinapur is bitterly argued over by the clans of Kaurav and Pandav. Mama Shakuni of the Kaurav clan plots to eliminate the Pandav as they build a new palace at Varanavratt by getting the architect to build flammable materials into the walls and then setting them alight while the Pandavs sleep. The five Pandav brothers manage to escape via a tunnel and, believed dead, hide in the forest. The brother Arjun then wins the hand of the lovely Draupadi in an archery contest but after their mother makes a mistaken comment about Arjun sharing his prize, all the brothers end up marrying her. The Pandavs go to claim their rightful throne and are granted a territory. There they build the fabulous palace of Indraprasth. Mama Shakuni still desires to bring the Pandavs down and invites them to a dice game. This proves disastrous for the Pandavs – first they lose all their wealth and lands, and then agree to accept exile for thirteen years. Finally, they lose Draupadi who is humiliated and stripped of her robe by one of the Kaurav princes, before Lord Krishna hears her appeals and appears, creating a magically endless robe that cannot be unravelled. As their years of exile end, the Pandavs return to reclaim their throne. When the Kaurav refuse to relinquish what is theirs, they prepare for war. Both sides appeal to Krishna for help and, though he vows to remain a non-combatant, he offers his help in ways that allow Arjun to understand the meaning of honour.

The Mahabharata is one of the key texts of Hindu religion. The text is epically sized, containing more than 100,000 lines of verse. (By comparison, this is four times longer than The Bible). The Mahabharata was written sometime between 300 B.C. and 300 A.D., derived from earlier oral traditions. The author is said to be the wiseman Vyas who also appears as a character in the early sections of the story. The crux of the story tells of the rivalry between two related dynasties – the Kauravas and the Pandavas – over the throne of Hastinapura. The story recounts the bitter and murderous rivalry between the two, how the Pandavas were cheated of their title and wealth in a dice game and sent to thirteen years in exile, culminating in their showdown at the battle of Kurukshetra, which lasted eighteen days and killed some six million people. At the battle, Lord Krishna, an avatar of the god Vishnu, revealed himself and ended up swaying the battle in favour of the Pandavas.

Attempting to make a 160-minute film out of such a vast text must be considered a daunting undertaking. (By comparison, the massively successful version of The Mahabharata made for Indian television between 1988-90 took 94 hour-long episodes to tell the entire story). The equivalent might by Dino De Laurentiis’s authoritative claim to film The Bible (1966) in 174 minutes and not making it much beyond selected highlights of The Book of Genesis. To their credit, the filmmakers keep to and cover most of the basics of the story concerning the rivalry between the two clans and the culminating battle, although have had to truncate or ditch a good deal of the side stories that run throughout the text.

We get nothing of the background of the two clans – how the Pandava father Pandu is cursed to a life of celibacy after shooting a brahmin in the form of a gazelle and his wife then sires five sons after calling on the gods to impregnate her; and how the Kaurava mother Gandhari gives birth to a ball of flesh, which she cuts into a 100 pieces that becomes the 100 sons of the Kauravas. Also eliminated is the parts of the story that occur after the Battle of Kurukshetra, which comprise more than a third of the full text of The Mahabharata, dealing with King Yudhishthira’s struggle to come to terms with the massive body count, the death of Krishna’s earthly form and the decision of the remaining Pandavas to walk to the gates of Heaven at the end of the world.

Some of the aspects of the story that are retained are highly truncated – notedly the recitation of The Bhagavad Gita, which comprises some 700 verses and has become regarded as a separate sacred text in its own right and is the basis of the modern Hare Krishna religion wherein Krishna manifests his true form to the archer Arjuna and speaks of the necessity of dharma (one’s duty to social order and universal harmony) and attaining yogic detachment from the world, which in the film is reduced to no more than a few key speeches. All things considered, Mahabharat appears to do a fair job of highlighting the dramatic basics of the story.

What we are concerned with here is Mahabharat as a film and the extent to which it works as an epic fantasy. The major problem I had with watching the film was in doing so as a Westerner. I was increasingly aware that I was viewing a film that was made for an entirely different ethnic and cultural audience to the one that I belonged. This in itself should never be a particular problem – after all, foreign language films are released to theatres all the time and numerous ones are reviewed on this site.

The problem here is that Mahabharat was made strictly for Indian/Hindu audience and makes no effort to explain its story outside of this culture. In severely condensing the original text, Mahabharat makes the assumption that its audience is familiar with many aspects of the story and it is only through a considerable amount of background research on the subject that I have been able to fully grasp what is happening on screen. The confusion is also added to by the huge cast of characters – all of whom are dressed almost identically and sport the same prettified masculine looks, such that it often becomes impossible to tell who is on what side, let alone tell one character from the other.

That said, Mahabharat has an undeniable colour and an epic sweep that captivates the imagination. The film was made in the mid-1960s when there was a fad in the West for Biblical epics – The Ten Commandments (1956), Ben Hur (1959), King of Kings (1961) etc. One does not know how to what extent this fad spread to India but Mahabharat feels like a film construed in a similar vein. What Mahabharat feels more like is an Indian attempt to copy one of the Italian sword-and-sandal films that came out around the same time after the massive success of Hercules (1958). In particular, there are a number of scenes where the various brawny men engage in extended wrestling matches, which suggests that the filmmakers were attempting to appeal to the same audience for muscleman adventure as the peplum cycle.

What Mahabharat has over the Italian films is a much more vivid sense of fantastic imagination, which was always something that was played down as much as possible by the Italians. There are some excellent optical effects for the era that allow the demon child Ghatotkatcha to grow to giant-size (in a scene undeniable reminiscent of the genii’s appearance The Thief of Bagdad [1940]), arrows to multiply as they fly through the air and carry their opponents severed heads away or spout streams of water when shot into the ground, or Krishna to appear in a giant-size incarnation with multiple heads atop his shoulders. One of the most magical scenes is where Draupadi is about to be stripped but Krishna appears and causes a robe to keep winding itself around her until her abuser is exhausted with the effort to unravel it. There is vibrant and lavish colour to the sets and costumes.

Dramatically, Mahabharat is less exciting. Director Babubhai Mistry shoots everything in wide angles and rarely breaks the drama up or focuses on any of the characters. There is also a wildly jaunty score run over every piece of action no matter what the occasion. Mahabharat does come into its own during the battle scenes, which are expectedly the highlight of the film and directed with a sizeable cast of extras. Even though the essence of The Bhagavad Gita has been drastically curtailed, one gets a fine sense during Krishna’s lectures of Arjun of learning his sense of duty and belief in a greater good that lies beyond the battle.

Other screen adaptations of The Mahabharata have been made in 1920 and 1933, although little is known about these. The most famous version was the massively popular tv series The Mahabharat (1988-90), which had the highest viewing audience of any show ever in India, and a remake Mahabharat (2013-4). In the West, director Peter Brook made the highly acclaimed The Mahabharata (1989), a mini-series that was shown in six one-hour episodes, as well as a three-hour theatrical version in some places.

(Review copy provided courtesy of Suresh S.)

Full film available here