(Kimitachi wa Do Ikiru ka)

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Hayao Miyazaki, Producer – Toshio Suzki, Photography – Atsushi Okui, Music – Joe Hisaishi, Art Direction – Yoji Takeshige. Production Company – Studio Ghibli.

The Science Fiction Horror and Fantasy Film Review

Director/Screenplay – Hayao Miyazaki, Producer – Toshio Suzki, Photography – Atsushi Okui, Music – Joe Hisaishi, Art Direction – Yoji Takeshige. Production Company – Studio Ghibli.

During the midst of World War II, eleven year-old Mahito Maki’s mother, a doctor, is killed during a fire at the hospital. Mahito and his father Shoichi move into the countryside where Shoichi has married his mother’s sister Natsuko who is now expecting a child. There Mahito is harassed by an annoying grey heron, which promises to reunite him with his mother. Mahito is drawn to explore an abandoned tower but is warned away from it. Natsuko then goes missing. Searching for Natsuko with the maid Kiriko, Mahito is drawn into the tower by the heron who promises to take him to her. This takes Mahito through into a strange world populated by birds where he must quest to find both Natsuko and his mother.

Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki has become an enormously revered talent in the West in recent years. After emerging from tv animation in the late 1970s, Miyazaki went on to direct Anime films such as The Castle of Cagliostro (1980), Nausicaa and the Valley of the Wind (1984), Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986), My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), Porco Rosso (1992), Princess Mononoke (1997), Spirited Away (2001), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004). Ponyo on a Cliff By the Sea (2008) and The Wind Rises (2013).

I have been less impressed with Miyazaki’s work as the 2000s dragged on. He hit a sublime height with Spirited Away, the point that the larger world discovered the joys of Miyazaki. Howl’s Moving Castle was not quite its equal but was a great follow-up to that. On the other hand, I remain far less enthused about the works that come after that point – Ponyo on a Cliff By the Sea and The Wind Rises. They are perfectly serviceable Miyazaki films and quite enjoyable in their own right, it is just that they sit as lesser works in comparison to the films that came before.

It may be that age is taking its toll – Miyazaki turned 82 the same year that The Boy and the Heron came out and completion of the film apparently dragged out much slower than usual (for seven years whereas his earlier films come 1-3 years apart). Not to mention every single one of these films that come after Spirited Away are ones where Miyazaki announced his retirement and then allowed himself to be dragged back in one way or another, so perhaps they are not as full or enthusiastic works as the earlier ones that were fired up by his imagination.

The Boy and the Heron is a renaissance of many Miyazaki themes and very much an autobiographical work. Like Mahito in the film, the young Miyazaki was born in the midst of World War II where his father was the manufacturer of parts for fighter planes for the war effort. Miyazaki’s mother was not killed in a fire but did suffer ill health during his formative years. Similarly, the Miyazaki family was forced to move from Tokyo and then a second time due to Allied bombing and relocated away from the city.

These elements weave into many of Miyazaki’s films. The relocation to the countryside and the ailing mother is a central plot aspect to My Neighbor Totoro, while the relocation also turns up as a lesser element of Spirited Away. Here the father is a manufacture of airplane parts – a fascination with various, sometimes oddball forms of flight turns up in most of Miyazaki films, while The Wind Rises is the biography of one such airplane designer from the WWII era. In both My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away, the new countryside home proves to be somewhere where the young child protagonist discovers a secret world filled with magical creatures. As in Porco Rosso and Spirited Away, there is also a thin diving line between the real world and the afterlife. And, as in almost all Miyazaki films, there is the sense of a young protagonist trying to grapple with complex adult emotions – in this case, the death of a parent and the acceptance of another woman in his father’s life.

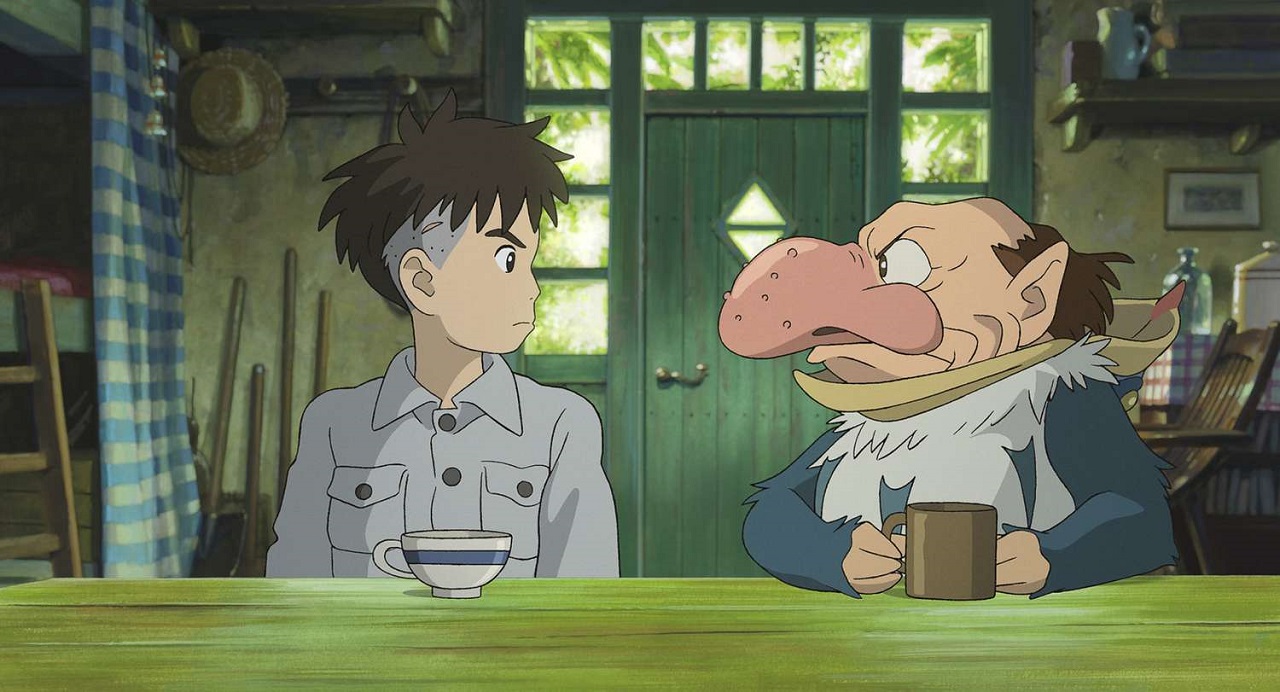

With The Boy and the Heron, I was initially expecting something like a boy befriends an animal type story – maybe something that landed in a similar wheelhouse to Studio Ghibli’s The Red Turtle (2016). However, the sometimes malevolent, tricksterish heron that we do get seems the almost complete antithesis of that, before in later scenes for reasons that were unclear to me being revealed to be a man inside. (Some interpretations have seen the heron as representative of Miyazaki’s relationship with mentor Isao Takahata or producer Toshio Suzuki, but without Miyazaki’s clarification this can only be speculation).

As you expect with Miyazaki, the world around Mahito is beautifully created, genteel in its pastorality. There are the magical creatures – a lot of birds and the particularly magical scenes where the warawara drift up into the sky to be born only to be devoured en masse by the herons. And there are the complex emotions you expect of a Miyazaki film, centred around the loss of a parent.

The Boy and the Heron is also a film that drew me into a certain magic but left me feeling adrift after a point. In the past, Miyazaki has created complex beautifully detailed worlds in works like Spirted Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, Nausicaa and especially Princess Mononoke, I was looking forward to that here but often the world we are in – it is never given a name – is one that seems a mix of elements that never assemble into a whole or underlying rationale. There are birds that sometimes talk; there are a series of what are called ‘grannies’ on the subtitles who act as servants in the countryside home but in the other world are either dolls or appear as their younger selves to aid Mahito; there are the souls of the warwara that travel up to be born, before being devoured by the herons who lack much else to eat; various animals are in the habit of mobbing Mahito.

There is great imagination here but it feels all over the place, left half unexplored. Who is the girl Himi who turns up and incinerates the birds? What are the ghost ships that sail on the horizon meant to mean? The scenes with Mahito being pushed into the graveyard, Mahito’s mother and the souls of unborn children would seem to indicate that we are in an Afterlife of some sort as opposed to a Fantasy Otherworlds, but it is not clear. There is a backhistory about how the tower was formed around the area of a meteorite impact, but that seems of no significance. We also get a hurried explanation later in the show about how the world is held together by the imagination of the person in charge, although it is not exactly clear who the person in charge is, why their imagination is causing a dysfunctional world and why someone of Mahito’s bloodline is required to take their place. And crucially, there is the figure of the titular heron who is major character who moves between being a full bird and a mean-spirited, grudgingly helpful human inside – who exactly this person or why they keep changing their form is unclear as well.

Spirited Away was also a film with a strange secondary world and creatures but you had a clear sense of the rules; with The Boy and the Heron you get the impression that Miyazaki was fairly much making everything up as he went along. You also feel that a good deal of this is meant to be allegorical – and certainly there are plentiful debates about the meaning of the film’s symbolism on various discussion boards around the internet – but there are no clear signposts as to interpretation of meaning.

Trailer here