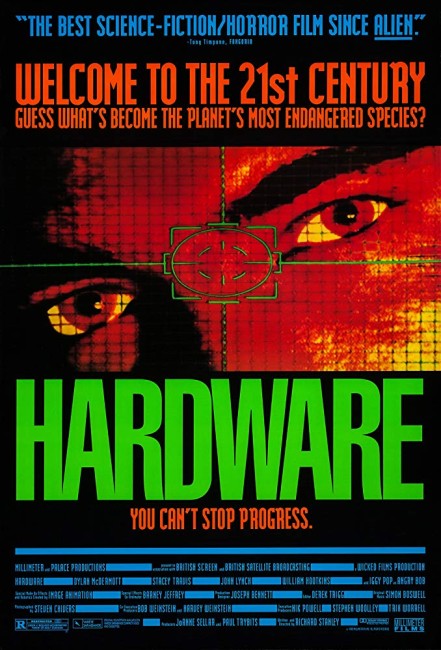

UK. 1990.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Richard Stanley, Producers – Joanne Sellar & Paul Trybits, Photography – Steve Chivers, Music – Simon Boswell, Special Effects – Barney Jeffrey, Makeup Effects – Image Animation, Production Design – Joseph Bennet. Production Company – Palace Pictures/Wicked Films.

Cast

Stacey Travis (Jill Grakowski), Dylan McDermott (Hard Moses Dexter), William Hootkins (Lincoln Weinberg Jr), John Lynch (Shades), Mark Northover (Alvy), Carl McCoy (Nomad)

Plot

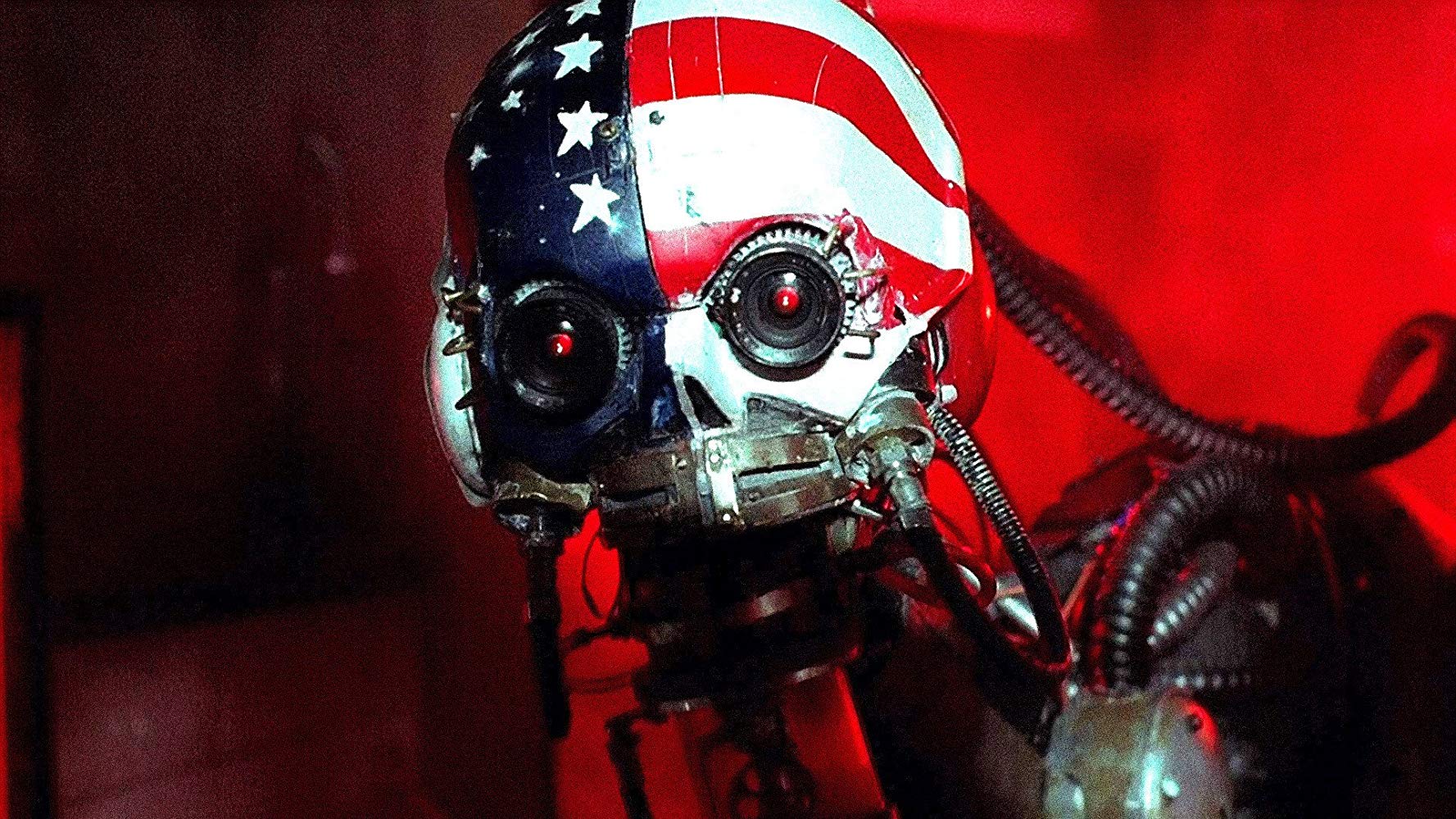

Space pilot Hard Mo Dexter buys a robot head from a junk scavenger as a present for his girlfriend Jill Grakowski. She uses it as the centrepiece of one of her sculptures. Unknown to her the head comes from a Mark 13 military robot, which is capable of rebuilding itself from virtually anything. The Mark 13 now takes over and turns Jill’s apartment into a lethal death trap.

The Cyberpunk subgenre with its densely visual clutter and focus on style and hi-tech detail is one that seems ready made for film even more so than literature. However, bar a few isolated examples – Blade Runner (1982), Johnny Mnemonic (1995), Nirvana (1997), tv’s Max Headroom (1985, 1987-8) and Wild Palms (1993) – the use of Cyberpunk on film has msotly served as a hook to hang action plots on.

Hardware is one exception, a pure evocation of Cyberpunk that arrives with a vision of the future that breathes the fumes of the cesspit and strikes like a bullet between the eyes. The background is filled with tiny throwaway details that immediately suggest an entire world existing beyond the frame of the film – a landscape dominated by factories where radiation infuses the atmosphere; wheeled taxis have now been converted to run on water canals; the clothing is junkpile chic; the hero has a cybernetic implant in lieu of a hand (something that is never even commented about); characters casually smoke marijuana cigarettes out of brand-name packets; in one startling momentary image a child is seen chained to a dead body on a stairwell; and on the soundtrack the voice of anarchic rock star Iggy Pop as a radio host announces “today’s good news is that there is no good news” and cheerfully lists the casualty figures from riots.

All the characters seemed burned to the edges in the film’s almost casual acceptance of a social nihilism. The most disturbing of these is William Hootkins who gives a tour-de-force performance as a neighbouring surveillance expert, slavering and sweating while photographing heroine Stacey Travis in the nude with an infra-red scope and then calling her to tell her about wanting to rectally violate her with a string of popcorn. It is a world where one can almost smell and feel the radiation in the air. (About the only thing that is missing from Hardware as a Cyberpunk film is the prediction of the prevalence of the internet).

Hardware has a dazzling, aggressive pace – the film is almost visually on fire with excitement. Everything comes at a maximum sensory input level of strobing lights and fractured editing, of sets washed in orange and red lighting and a dense clutter of begrimed, nearly broken down technology such that one almost perceives the film at the level of sensory overload threshold. Director Richard Stanley generates an enormous tension in scenes with the robot shredding the bed and probing through the refrigerator as Stacey Travis tries to hide from its infra-red targeting. The end of the film with the almost operatic, slow-motion death of the robot and its abstract computer images becomes a uniquely arty dance of technology and Cyberpunk texture.

The plot is on the slim side – and even that, as a lawsuit later established, was uncreditedly taken from the story Shok! (1980) in an issue of UK’s 2000 AD comic-book – but the sheer density of the film’s visual texture enthralls. For the relative low-budget that Hardware was made on – less than $1,500,000 – what is achieved is an authentic miracle. A film like this conveys a more credible picture of the future in ten seconds than an over-budgeted turkey like Freejack (1992) does in its entire running time.

Sadly despite such an assured debut here at the age of 24, director Richard Stanley’s subsequent career has gone into a tailspin. His next film was the fascinating and haunting supernatural serial killer film Dust Devil (1992) but this was plagued by distributor interference and has been little seen. Stanley next signed on for the big-budget remake of The Island of Dr Moreau (1996), only to be caught up and dumped by studio interference and actor egos not far into shooting. Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau (2014) is an utterly fascinating documentary about the disaster.

Although he has announced several dramatic projects, the only feature-length work that Stanley has made since then has been The Secret Glory (2001), a documentary about the Nazi’s obsession with the Holy Grail and the voodoo documentary The White Darkness (2002), before making a return to genre material with the Mother of Toads episode of the horror anthology The Theatre Bizarre (2011) and the feature-length H.P. Lovecraft adaptation Color Out of Space (2019), as well as co-writing the ghost story The Abandoned (2006) and the horror film Replace (2017). Richard Stanley is great grandson of the famous African explorer Henry Morton Stanley (of Stanley and Livingstone fame).

Trailer here