Crew

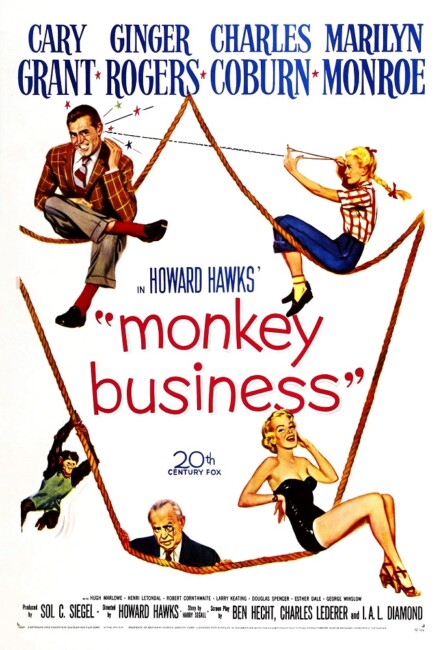

Director – Howard Hawks, Screenplay – I.A.L. Diamond, Ben Hecht & Charles Lederer, Story – Harry Segall, Producer – Sol C. Siegel, Photography (b&w) – Milton Krasner, Music – Leigh Harline, Special Photographic Effects – Ray Kellogg, Makeup – Ben Nye, Art Direction – George Patrick & Lyle Wheeler. Production Company – 20th Century Fox.

Cast

Cary Grant (Professor Barnaby Fulton), Ginger Rogers (Edwina Fulton), Charles Coburn (Oliver Oxley), Marilyn Monroe (Lois Laurel), Hugh Marlowe (Hank Entwhistle)

Plot

Absent-minded research chemist Barnaby Fulton is trying to perfect a rejuvenation formula. An experimental monkey gets loose in the laboratory and, unseen by others, indiscriminately mixes chemicals together and tosses them in the water cooler. This causes Barnaby and all those who unwittingly drink the water to mentally revert to adolescence.

Howard Hawks (1896-1977) is considered one of the great American directors. Hawks made 41 films in which he was the credited director. These included classics that range from the original version of Scarface (1932), the screwball comedies Bringing Up Baby (1938) and His Girl Friday (1940), the war film Sergeant York (1941), the Westerns Red River (1948) and Rio Bravo (1959), among many others. Hawks became identified with a sharp dialogue-driven style and for featuring a sparring relationship between the sexes. The only other genre film that Hawks is known for is the alien invader classic The Thing from Another World (1951) where he acted as producer and where common belief insists that the film itself was directed by Hawks, even though he takes no director’s credit.

Monkey Business is regarded as a classic. Hawks arranges an amazing cast line-up – Cary Grant at the peak of his stardom (essentially doing a repeat of his role in Hawks’ Bringing Up Baby); dancer turned actress Ginger Rogers most known for her pairings with Fred Astaire; and a then relatively unknown Marilyn Monroe in a supporting role as Grant’s airheaded secretary. (Indeed, this is the only film that Marilyn Monroe will be listed for on this site).

Monkey Business came early in Monroe’s career – just before her major breakout role in Don’t Bother to Knock (1952) – and is the sort of parts that she spent her moment in the spotlight fighting against being cast in – a blonde whose dumbness is an object of comedy. Sample line: “Mr Oxley’s been complaining about my punctuation, so I’m careful to get here before 9.” (She fared much better when Howard Hawks cast her in the musical Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) the following year where she delivered one of her most memorable performances).

The 1950s was all about the rise of the American middle-class. Advertising came into its own and began to target the middle-class consumer where the ideal of the nuclear family became venerated as the aspirational norm of society. Underneath that, there were some voices of discontent that were unhappy at the straight-jacketedness of the lifestyle it entailed. Women were relegated to a secondary position, children were required to merely obey, non-whites didn’t even get a look in. This found open voice a few years later with the restlessness of Jack Kerouac and the rise of the Beat Generation, before the open rebellion of the hippies.

As seeming contrast to this controlled life, there were several films around this period that advocated abandoning seriousness and embracing frivolity. There was the classic and very popular Harvey (1950), which contended that the mad enjoyed life far more than everybody else, and other works like Miracle on 34th Street (1947) and The Luck of the Irish (1948) that argued for eccentric beliefs as having perfect legitimacy alongside taking life seriously. Monkey Business likewise advocates throwing solemnity up in the air and embracing a return to adolescence.

The opening scenes are filled with the dullness of absent-minded Cary Grant (who spends much of the film wearing thick coke bottle glasses) and his dedication to the job and wife Ginger Rogers fussing about attending a dinner party. The rest of the film is filled with scenes designed to throw these shackles off where dull Cary Grant suddenly does radical things like buying a sporty blazer and an open-top speedster, goes recklessly driving with secretary Marilyn Monroe and spends the afternoon at the swimming pool instead of work (during which his myopia also seems to spontaneously correct itself). After drinking the water, Ginger Rogers puts a goldfish down Charles Coburn’s pants and wants to go dancing.

The film reaches it heights of silliness during the climax where Cary Grant puts on warpaint and joins a group of kids playing Cowboys and Indians, persuading them to tie up and scalp his romantic rival Hugh Marlowe, while there is also much comic silliness with the monkey going amok in a boardroom. It is an amazingly silly film. It may have attained a classic status but the upshot of it seems to be a celebration of infantile behaviour. If one’s idea of comedic heights are watching Cary Grant and Ginger Rogers acting like five-year-olds and slapping each other with paint then by all means enjoy.

Monkey Business and especially Disney’s The Absent-Minded Professor (1961) a few years later could be accused of taming the mad scientist. Throughout the 1930s and 40s, the scientist was regarded as the defiler of divine provenance whose experiments were always doomed to failure. This suddenly changed in the 1950s where the character became a lovable eccentric and his absent-mindedness the subject of comedy. It is almost as though Monkey Business acted as template for The Absent-Minded Professor – there is the same triangle between the scientist who ignores his wife and her old flame who tries to woo her back, the same discovery of a substance that unleashes a flurry of chaos and eccentricity. Of course, the one thing that was missing in the Disney sanitised version of The Absent-Minded Professor was the pure sizzle of Marilyn Monroe.

Full film available online here:-