UK. 1965.

Crew

Director/Screenplay/Producer – Peter Watkins, Photography (b&w) – Peter Bartlett, Makeup – Lilias Munro, Production Design – Tony Cornell & Ann Dave. Production Company – BBC.

Cast

Michael Aspel & Dick Graham (Narrators)

Plot

The world teeters on the brink of nuclear war as the USSR invades West Berlin. Despite the government’s attempt to educate people about how to survive a nuclear war, the English public remain woefully ignorant and most precautionary measures are too expensive for the average family. A nuclear strike then hits London and millions are killed. In the aftermath, authorities have to cope with the thousands of burn victims, the burying of the dead, martial law, food riots and their own personnel snapping under the stress.

Originally, this 48-minute pseudo-documentary was commissioned by BBC tv to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of Hiroshima but it has since become a work of legend. After viewing by BBC executives, the film’s grimly realistic, no-holds-barred portrayal of nuclear war was deemed too shocking for public viewing and it was banned. Although, in more recent years there has come to be a number of voices questioning that the real reason for the film’s banning was not so much that it was too horrific, but because it questioned government policy on nuclear defence and was seen as being actively propagandist on the part of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. The British Home Office even intervened during production, withdrawing initially offered help in providing statistics and refusing to allow civil defence authorities to participate in the filming.

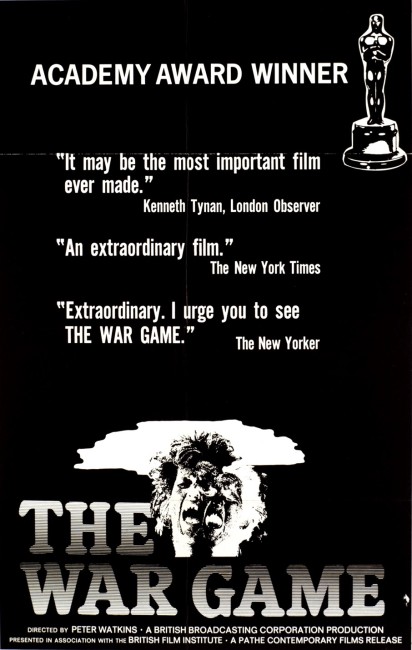

Director Peter Watkins responded to the ban by actively advocating for the film’s release with a letter-writing campaign to newspapers and was eventually given permission by the BBC to show the film theatrically but not on television. After screening in cinemas, The War Game won a number of awards, including the 1967 Academy Award for Best Documentary. It may well be a testament to the film’s power to shock that it was not until 1985, some twenty years later, before the ban was lifted and the BBC screened it on air. Around this time, the BBC also appropriated Watkins’ pseudo-documentary style with the more fictionalised but also brutally grim tv movie Threads (1984).

Director Peter Watkins was influenced by the French and Italian neo-realists and became fascinated with the concept of fictionalised documentary – of historical incident reconstructed and shot in cinema verite style as though it were a real documentary (something that has in recent years been termed the Mockumentary). Watkins had earlier made two such short pseudo-documentaries Diary of an Unknown Soldier (1959), a reconstruction of conditions in the trenches in World War I, and The Forgotten Faces (1960), a re-enactment of the people’s revolt against the Communists in Hungary in 1956. These led to him being commissioned to make two pseudo-documentaries for the BBC. The first of these was Culloden (1964) where Watkins restaged the famous 1746 Scottish battle and took his camera onto the battlefield to ‘interview’ the participants. This was a huge success and Watkins then moved onto The War Game where he perfected the pseudo-documentary style with an alarming degree of realism.

To take such a grim subject matter and portray it in cinema verite stylism – of jerky, handheld camerawork and raw background noise and in specifically pegging it to a lower-class East End London milieu – is something that only tightens the unnerving authenticity of the subject matter. Once the bomb hits, the detached third-eye observer point-of-view allows for the staging of scenes of shocking impact – the burning of disease-infected bodies; of food riots, culminating in the execution of rioters by firing squad; visions of hospitals overrun by burn victims and of police having to shoot those with burns on more than 50% of their bodies; the collecting of wedding rings in a bucket for hopeful future identification of bodies; the lady interviewed who tells how her family have to bathe in and drink from the same bath of water; the soldiers cracking under stress and being shot for refusing to remove bodies. It is doubtful the real thing could ever be more unrelentingly bleak in impact. (Fr a more detailed overview and a list of other films on the topic see Films About Nuclear War).

Peter Watkins did an amazing amount of research to make sure that his facts, figures and surmises were authentic. Many of the interview subjects on screen – like in the scenes where ordinary housewives are asked about the effects of Carbon 14 – are not actors but actual people on the street being questioned. You can understand why the government became uncomfortable about the film – Peter Watkins holds nothing back in his critique of their inadequacies and the grim reality that people would face. The events are given an even darker underlining by contrast during the early scenes with US and even Vatican lecturers insisting that the war should be thought about positively. The only stone that is left unturned is dealing with the issue of radiation fallout.

The effect is occasionally mitigated by the film’s stopping for the narrator to stand back and solemnly intone “This is what could happen in the eventuality …,” an corollary that is resoundingly obvious and contrarily defuses impact by jolting us out of the suspension of disbelief that we only too willingly give the film. The greatest horror of it all is not only that it could happen, but that most of it already has, Peter Watkins having derived much of the material here from accounts of what happened at Dresden and Hiroshima. His parting reminder that there is twenty tons of high explosive for every person on the planet comes like a final, concluding bullet fired right between the eyes of the audience as they depart.

Following The War Game, Peter Watkins branched out into a career as a cinematic director, making a series of politically charged films that challenged the establishment and which make frequent use of the pseudo-documentary style. He made several other ventures into science-fiction:– Privilege (1967) set in a near-future where a pop star is manipulated by the government to control youth; The Gladiators/The Peace Game (1969) set in a future where war has been negated and countries instead settle their differences by selecting armies to fight one another in war games; and Punishment Park (1971) set in a future where several political prisoners are given the opportunity to win their freedom by crossing a desert.

After his censorship problems, Watkins has never worked for the BBC again and has resided in Sweden since the late 1950s. His work throughout the 1970s and 80s has been sporadic and has consisted of a series of mostly uncompleted projects or works for Scandinavian television. His other non-genre films include:– Edvard Munch (1974), a biography of the painter; Evening Land (1977), another fictionalised documentary that questions Denmark’s model society (and which was deeply controversial); The Journey (1987), a 14 hour documentary work shot in several countries around the world analysing the effects of war and mass media; The Freethinker (1994), a biography of the Swedish writer August Strindberg; and La Commune (2000), a pseudo-documentary set in an artist’s community during the French Civil War of 1871.

Clip from the film here