USA. 2000.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Michael Almereyda, Based on the Play by William Shakespeare, Producers – Andrew Fierberg & Amy Hobby, Photography – John de Borman, Music – Carter Burwell, Music Director – Beth Amy Rosenblatt, Production Design – Gideon Ponte. Production Company – Double A Films.

Cast

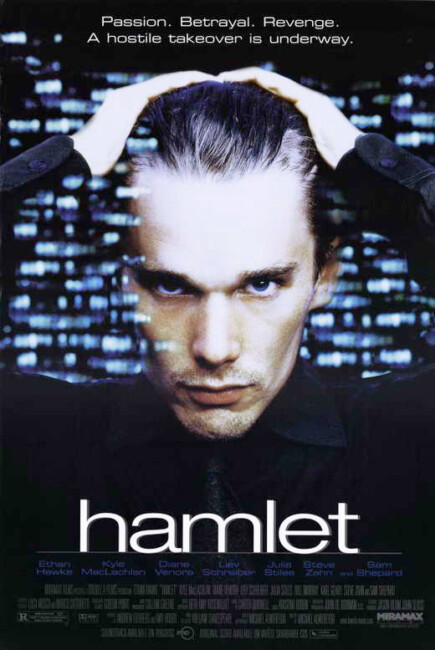

Ethan Hawke (Hamlet), Julia Stiles (Ophelia), Kyle MacLachlan (Claudius), Diane Venora (Gertrude), Bill Murray (Polonius), Liev Schreiber (Laertes), Sam Shepard (The King), Karl Geary (Horatio), Steve Zahn (Rosencrantz), Dechen Thurman (Guildenstern)

Plot

The year 2000. The CEO of Manhattan’s Denmark Corporation has died. His son Hamlet returns from school to find that his mother has married his uncle Claudius and that Claudius has now been promoted to CEO. Holed up in the Elsinore Hotel, and all the while wooing the lovely Ophelia, Hamlet is visited by his father’s ghost who tells him that Claudius poisoned him. Wracked with indecision, Hamlet hatches a scheme to prove his uncle’s guilt using a video collage.

The 1990s/early 00s saw a revitalisation, almost a hunger, for Shakespeare adaptations. The way was led by Kenneth Branagh with his bold, dynamic versions of Henry V (1989), Much Ado About Nothing (1993), Hamlet (1996) and Love’s Labor Lost (2000). In so doing, Branagh opened up a new cinematic Shakespeare – one that was inherently visual in nature, as opposed to merely being filmed stageplays; one that made bold and exuberant use of the full screen canvas; and one that cast name actors, often in parts that considerably challenged typecasting, in order to draw wider audiences in. A host of Shakespeare adaptations followed suit.

The most radical among these were those that restlessly played with the story’s setting. Not just minor period relocations like Branagh updating his Hamlet to a post-Napoleonic Denmark or A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1999) being moved from Ancient Greece to 19th Century Tuscany, but radical reinventions like placing The Taming of the Shrew in a high-school setting in 10 Things I Hate About You (1999), retelling Othello on a high school basketball court in O (2000), retelling Romeo and Juliet with garden gnomes in Gnomeo & Juliet (2011), or Julie Taymor’s Titus (1999), easily one of the best of the non-Branagh adaptations, which placed Titus Andronicus in an alternate world of sorts where Roman centurions rode motorcycles and played videogames. Or else Peter Greenaway’s wholly eccentric take on The Tempest in Prospero’s Books (1991) as a kind of MTV-styled freewheeling mardi gras, and Branagh conducting Love’s Labor Lost as a musical. The BBC even produced a tv series, ShakespeaRe-Told (2005), which redid a number of Shakespeare plays in modern setting and dialogue. The year prior to this had also seen Hamlet modernised with Let the Devil Wear Black (1999).

The most popular of these reinventions was Baz Luhrman’s Romeo +& Juliet (1996), which has much in common with Michael Almereyda’s Hamlet here. Like Luhrman, Michael Almereyda transplants Shakespeare into the modern world – although in both cases this is more like an alternate contemporary world where people happen to speak in Elizabethan prose.

Like most of these modernised versions, you end up applauding the audacity of the modernisation – here Denmark is a corporation and its political in-squabblings are now the fight for the title of CEO; Elsinore is now a hotel where Ophelia suicides in the lobby fountain; and Shakespeare’s speeches are delivered by fax and cellphone, while Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s missive to the King of England is delivered on floppy disk. Both films also star a popular twentysomething actor – Leonardo Di Caprio in Romeo +& Juliet, Ethan Hawke here. The crucial difference is that where Romeo +& Juliet was a box-office hit, Hamlet ended up doing the backwaters of the arthouse circuit. The difference of course is all in the story – Romeo +& Juliet‘s was the wonderfully tragic tale of two young lovers, one being played by an actor that teen girls wet their panties over; Hamlet on the other hand is a far less sexy story about political backstabbing where the teen heartthrob is stricken by angst and indecision throughout. There is no easy multiplex sell to it.

Most of Michael Almereyda’s films are updatings of old stories – Nadja (1994) was a modernisation of Dracula’s Daughter (1936), The Eternal/Trance (1998) was a striking revision of the mummy film. Almereyda has called this a millennial Hamlet. It is without a doubt is a postmodern Hamlet, one where Hamlet’s cries of confusion are echoed at every turn by the recorded image. Thus Hamlet makes camcorder videos of his own speeches and replays them throughout; his “To be or not to be” speech is prefigured by the philosophising of a Buddhist monk on tv, while the actual speech takes place, with heavy-handed symbolism, in the Action section of a Blockbuster videostore. The trap Hamlet lays to prove Claudius’s guilt is not a play but a film composed of sampled video images. It is a Hamlet that has been reconstructed as an fable of postmodern identity crisis – one where a media-saturated world comes to echo, mirror and amplify the crises of indecision that run through the central character’s head only to ultimately abandon him under its oblique eye.

Michael Almereyda subsequently went on to make the strange and baffling Happy Here and Now (2002) about the search for a woman who has gone missing on the internet. For the next decade, Almereyda’s work has consisted of a handful of documentaries, before returning to fiction with another modernised Shakespeare adaptation Cymbeline (2014), the acclaimed Experimenter: The Story of Stanley Milgrim (2015), his best film to date, the sf film Marjorie Prime (2017) set in a future where people recreate holograms of their departed loved ones, and the biopic Tesla (2020).

Trailer here