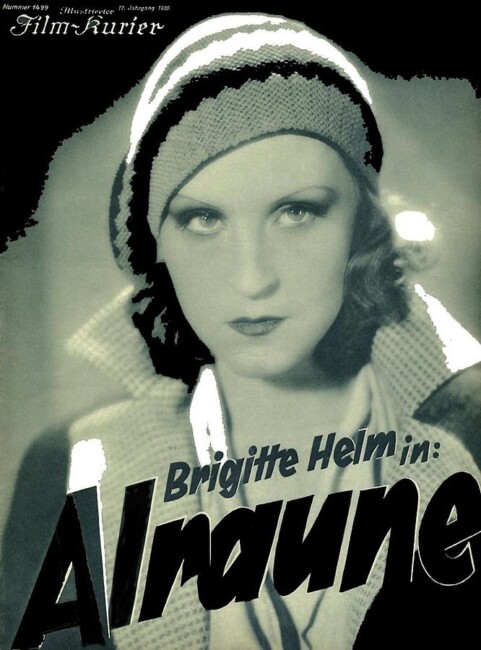

aka A Daughter of Destiny

Germany. 1928.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Henrik Galeen, Based on the Novel by Hanns Heinz Ewers, Photography (b&w) – Franz Planer, Production Design – Max Heilbronner & Walter Reimann. Production Company – Ama-Film GmbH.

Cast

Brigitte Helm (Alraune/Mandrake ten Brinken), Paul Wegener (Professor Jakob ten Brinken), Wolfgang Zilzer (Wölfchen), Louis Ralph (The Magician), John Loder (The Viscount), Ivan Petrovich (Franz Braun), Hans Trautner (The Trainer)

Plot

The celebrated geneticist Professor Jakob ten Brinken recruits his nephew Franz to help with an experiment. The Professor wants to prove that genetics have no influence over human development. To such end, he asks Franz to procure a woman who is the scum of the streets and then impregnates her with the seed of a hanged murderer. Franz and all the other scientists that the professor shows his notes to call the experiment an abomination. The resulting child is named Alraune or Mandrake. Growing up as a young woman, Alraune has no emotions and is able to seduce and coldly manipulate men at her whim. She runs away from the convent school where the professor places her and passes through a string of lovers. The professor finds her where she is working as a magician’s assistant at the circus and brings her back home. However, when she reads his notes and learns of her origin, Alraune determines to take revenge on the professor by sparking his jealousy.

Alraune is a classic of the great era of German Expressionist cinema. During the silent period between the two World Wars, Germany produced an amazing series of fantastic films. This was the era that led to classics such as The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919), Nosferatu (1922), The Hands of Orlac (1924) and Fritz Lang works such as Dr Mabuse, The Gambler (1922), Siegfried (1924) and Metropolis (1927) to name but the most famous.

Alraune (1911) was originally a novel written by Hanns Heinz Ewers, a German actor/writer who became a Nazi sympathiser in later years. Ewers was a popular writer and did some film work – most notably writing the script for the original The Student of Prague (1913) about a student’s pact with The Devil, which has been multiply remade. Alraune was filmed a number of times during this era. The first of these was the Hungarian Alraune (1918), co-directed by the celebrated Michael Curtiz, later the director of Hollywood classics like Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Casablanca (1942), with Gyana Gal as Alraune. This version is believed to be lost today. This was followed by a German version Alraune (1918) starring Hilde Wolter, of which a surviving print has turned up. There was Alraune and the Golem (1919), which would supposedly cross the character over with Paul Wegener’s character from The Golem (1914), although it is generally believed that this was never made – if so, all prints have been lost and no records of it screening have ever been discovered. This 1928 version is the most famous of the adaptations and the most widely available today (even if it can only be seen in censored form). This was given a sound remake Alraune/Daughter of Evil (1930) a mere couple of years later, also starring Brigitte Helm. The last version of the film to date has been Unnatural (1952), which starred Hildegard Knef as Alraune and Erich von Stroheim as the scientist. No further versions have been made, quite possibly to the datedness of its genetics debate, although the basic idea was given a modern overhaul as Embryo (1976) starring Rock Hudson and Barbara Carrera.

Alraune was directed by Henrik Galeen. Galeen was better known as a screenwriter, having written the screenplays for several classic films from the era, including the remake of The Golem (1920), Nosferatu and Waxworks (1924). He had co-directed with Paul Wegener the lost 1914 version of The Golem and went onto direct the remake of Hanns Heinz Ewers’ The Student of Prague (1926). (Galeen is also portrayed as a character in the German Expressionism homage Shadow of the Vampire (2000), played by Robert Aden Gillett). As the role of the scientist, Galeen recruited his Golem star/co-director Paul Wegener. As the title seductress, Galeen cast Brigitte Helm who had just made a sizzling debut the previous year as the robot Maria in Metropolis.

Alraune lays down much of the essence of mad science cinema that would overtake Hollywood in a matter of years. Paul Wegener is the scientist who recklessly pursues an experiment; while everyone who reads his notes cries horror, abomination and claims that it is against nature; and with Frankensteinian effect, his creation turns against him and determines to affect her creator’s ruin. The one thing that Alraune weds this to – something that Hollywood mad science cinema never did – is the idea of a femme fatale, a woman oozing with sexuality and desirability who drags men to their doom. Alraune creates such a strong sense of this that you almost get the impression that Hollywood mad science cinema felt they had to censor out any suggestion of sexuality by comparison.

German silent cinema of this period was deeply divided. It seemed to stand with one foot in superstition, a mythological past and a Mediaeval worldview – works like The Student of Prague, Siegfried, F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926) – and works that turned to modernism and celebrated the transport and engineering revolutions that were taking off around the time – as can be seen in the likes of Metropolis, Woman in the Moon (1929), FP1 Does Not Answer (1932), The Tunnel (1933) and Gold (1934). However, this reach for modernity was also fearful. Metropolis in particular feared the human cost of the revolution and saw its scientist not as a rationalist but an alchemist. Alraune similarly sits straddling the fence between modernism and superstition – the very opening scenes of the film cut from the Mediaeval legend of the mandrake root to Paul Wegener talking about genetics.

Alraune is essentially a position paper about the idea of artificial insemination. Real-life experiments began in Russia in 1899 with the scientist Ilya Ivanoff successfully artificially inseminating several different animal species. News of this was just getting to the west by the time of Hanns Heinz Ewers’ novel and had inflamed into a public debate about the consequences of experimentation on humans by the 1920s with much wildly misinformed voices from religious conservatism decrying it as unnatural. As such, Alraune enters into the debate on the subject with the wild alarmism of a tabloid headline. It is also hard not to see in some of this the embryo of the Nazi take on blood and genetics – with the idea that some people are just rotten, evil and socially inferior according to genetic predestination. At one point, we see Paul Wegener’s scientist ordering his nephew to go and obtain a woman who is “the scum of society” as the vessel for his killer’s seed.

Not merely that, Alraune is also a deeply misogynist film. It is anti-female sexuality, equating untamed female sexuality with evil. The entire film seems to exist as a paranoid rant about the evils of woman leading men on, callously using them and betraying them. There is a direct equation between Brigitte Helm acting seductive and sexually wanton and her being born without emotions, as though to say a woman who is properly emotional would not act in such a wilful and overt manner. Yet after creating such a strong figure of a femme fatale, the film reaches an extremely lame ending. Despite building up the dangers of a woman born without emotions, it simply has her finding the right man and walking off to find true love, while Paul Wegener’s scientist is left condemned to a life alone because of his crimes against nature. All of which seems to say that uninhibited female sexuality is evil, that a woman’s true place is tamed and settled down with the right man. Today all of this hysteria seems absurdly tame. Society has accepted artificial insemination with barely any notice, let alone moral collapse. Moreover, it seems almost impossible to think about getting worked up and regard as horrific the idea of a woman asserting her sexuality and enjoying the company of multiple lovers in the modern era. Made today, Alraune would not even rank as a horror film.

The complaint you could make is that Alraune is a dull film. Compared to the astonishing cinematic things that were being done in the era by other directors such as Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, Robert Wiene and Paul Leni, Alraune is flat and unimaginative. It seems lacking in any of the stupendous architectural fantasy that other works of the German Expressionist era made almost mandatory. Henrik Galeen does conduct Expressionist stylistics upon a couple of occasions – one scene where Brigitte Helm discovers who she is and her exaggerated shadow plays out on the wall as she reels in confusion; another a few minutes later as the shadows of her hands are seen creeping across the sleeping Paul Wegener’s chest as she contemplates strangling him – but these seem relatively crude directorial effects.

The one thing that stands up above Henrik Galeen’s unremarkable direction is Brigitte Helm’s performance. A constant teasing sexuality lies beneath the film – the way the magician shows her his mouse and then places it up under her skirt; the way she and the ringmaster light cigarettes in either’s mouth, which becomes like a smoke-shrouded kiss. Helm with tall, thin body and angular boned face does a magnificent job looking seductive and evil – her performance is all heavily meaningful lidded stares with single curled, upraised eyebrow. There is a fine scene where she tries to tempt Paul Wegener, dropping the wrap from her bare back in front of him, sitting on the chaise lounge, stroking his leg with her shoe and caressing his hand as he offers her a cigarette, before languorously lying back for him to light it for her.

The English-language version of Alraune in existence today (the one in the YouTube link below) is unfortunately the one that has been cut by the British censor. Thus all reference to the circumstances of Alraune’s birth are eliminated from the film, as well as any mention of the mother being a prostitute. The film abruptly and confusingly cuts from the mother brought in by the nephew to Alraune as a fully matured woman now in boarding school with no explanation of anything in between. A restored version was screened in Germany in 2000, although this is not widely available at present.

Full film available here