(Wachsfigurenkabinett)

Crew

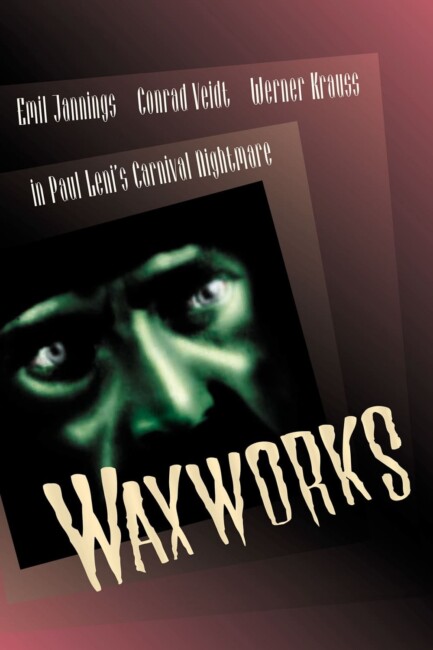

Director – Paul Leni, Screenplay – Henrik Galeen, Photography (b&w) – Helmar Lerski, Production Design – Paul Leni & Ernst Stern. Production Company – Neptun.

Cast

Wilhelm Dieterle (Writer/Assad), Olga Belajeff (Waxworks Proprietor’s Daughter/Zarah/Russian Nobleman’s Daughter), Emil Jannings (The Caliph), Conrad Veidt (Ivan the Terrible), Werner Krauss (Jack the Ripper), John Gottowt (Waxworks Proprietor)

Plot

A writer accepts a job from a waxworks proprietor to write a series of stories about the various exhibits in his museum in order to drum up business. In the first story, the Caliph of Baghdad is drawn to the wife of the baker Assad who lives beneath his walls. When his wife’s ego swells at the attention, Assad tries to prove himself by sneaking into the palace and stealing the ring from the sleeping Caliph’s finger. When the ring will not come off, he in desperation severs the Caliph’s hand. The second story is of Ivan the Terrible, who causes great misery at a wedding he is invited to but is then driven insane, thinking that he has been poisoned. The writer then falls asleep where he dreams of the curator’s daughter being pursued by Jack the Ripper.

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919) revolutionised a new school of filmmaking in Germany with its subjective presentation of the contorted inner world of a madman. Few films took up the challenge of directly following in Caligari‘s footsteps by recreating such a stylised inner world but many films adopted Caligari‘s sense of design in one way or another – it can be seen in everything from The Golem (1920) to Nosferatu (1922), Dr Mabuse, The Gambler (1922) and Metropolis (1927). Many of the films of this period were fantasy – indeed, the German Expressionist era is, at least in this author’s opinion, the most unbridled era of pure fantastique imagination in cinema. (For a more detailed overview see German Expressionism).

Waxworks resembles the portmanteau-styled cross-historical fantasy of Fritz Lang’s Destiny (1921), which in turn was influenced by D.W. Griffith’s epic Intolerance (1916). The frequent reviewing of Waxworks as a horror film (based on the brief final Jack the Ripper segment) has given the misleading impression that it is a horror film, although it is more of a fantasy.

The first two episodes work the best, being written with a nicely fabulist succinctness that in both cases work to provide charmingly ironic endings – these are models of what all anthology stories should be. The Ivan the Terrible episode is crowned by a memorably hollow, haunted and genuinely mad performance from Conrad Veidt. The final image with him twisting the hourglass over and over, mimicking the gesture in the air with his hands in a vain attempt to turn back the poison it measures is wonderful. Nothing much emerges from the celebrated Jack the Ripper episode. Annoyingly, at least in the translation, this confuses Jack the Ripper with the very different legend of Spring-Heeled Jack. The sequence only lasts for two minutes, consisting of the heroine being stalked, and then abruptly ends.

The design work in the film is amazing – Baghdad in the Caliph episode is presented as a series of labyrinthine streets that look like ants have burrowed through a Lego set; while the hero’s house is built like the interior of a weirdly claustrophobic clay oven that squats in the giant shadow of the Caliph’s dome, its chimney snaking all the way around the outside of the minaret like a spider’s leg.

The Ivan the Terrible sequence builds on the formal imagery of the Russian Orthodox Church, turning its icons and costumery into at times bizarrely stylised effects. The Jack the Ripper episode gives the impression of being a remake of Caligari as directed by Rene Clair, all presented through a mind-bending array of distorted lens, shadow lighting effects and double-exposures.

Director Paul Leni emigrated to the US where he became a highly promising silent director, making the classic Old Dark House film The Cat and the Canary (1927), the Charlie Chan film The Chinese Parrot (1927), the lavish historical horror The Man Who Laughs (1928) and the Old Dark House thriller The Last Warning (1929). Alas, in 1929, Leni died of blood poisoning and the world was deprived of a potentially amazing director.

Full film available here