(Kaidan)

Japan. 1964.

Crew

Director – Masaki Kobayashi, Screenplay – Yobo Mizuki, Based on Short Stories by Lafcadio Hearn, Producer – Shigeru Wakatsuki, Photography – Yoshio Miyajima, Music – Toru Takemitsu, Art Direction – Shigemasa Toda. Production Company – Ninjin Club/Bungei

Cast

Black Hair:- Rentaro Mikuni (Samurai), Michiyo Aratama (First Wife), Misako Watanabe (Second Wife). Snow Woman:- Tatsuya Nakadai (Minokichi), Keiko Kishi (Oyuki). Hoichi the Earless:- Katsuo Nakamura (Hoichi), Rentaro Shimura (Priest), Joichi Hayashi (Yoshitsune). In a Cup of Tea:- Ganemon Nakamura (Lord Nakgawa), Noboru Nakaya (Shikibu Heinai)

Plot

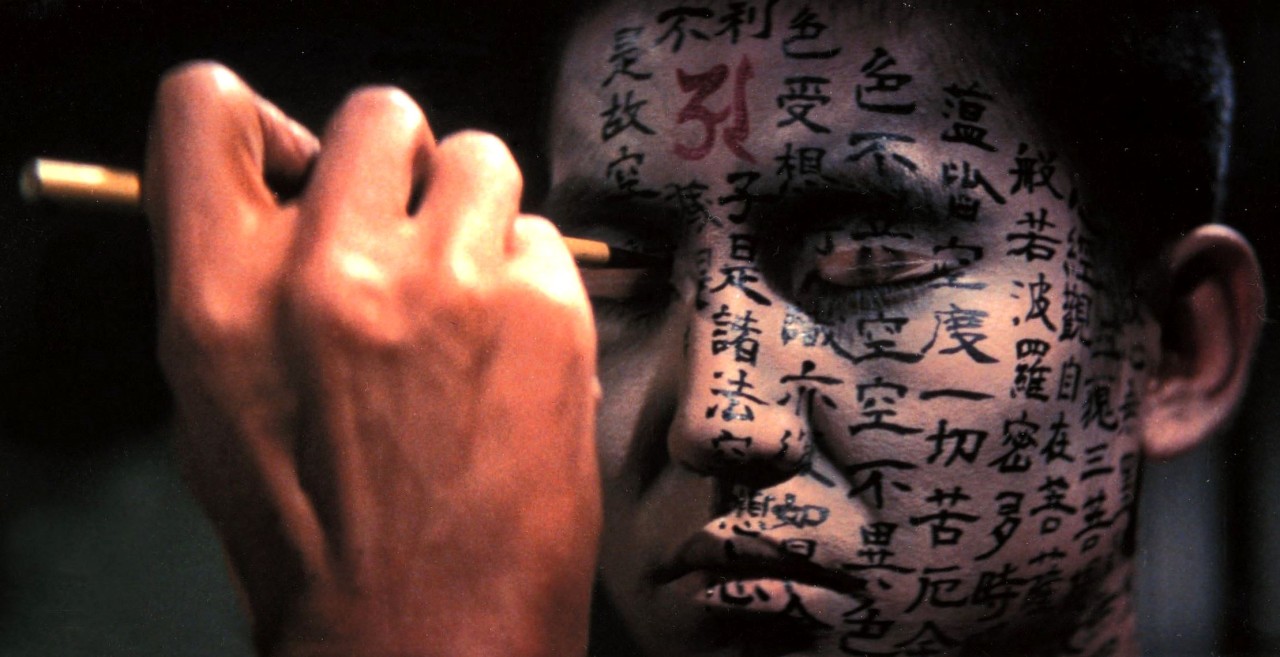

Black Hair:- A poor samurai divorces his wife and marries the daughter of a wealthy man so that he might advance in his profession. However, his second wife is a selfish woman and the samurai longs for his first wife whom he loved. Eventually he returns and spends the night with her, only to wake and find a skeleton in the bed. Snow Woman:- An aging woodcutter and his apprentice are caught in a hut in the midst of a snowstorm. The apprentice wakes to find a beautiful woman of the snows feasting on the blood of his master. The snow woman agrees to spare him on the condition he will never tell anybody about her. Hoichi the Earless:- The blind monk Hoichi is held in high repute for his singing of epics. His fellow monks then discover that Hoichi has unwittingly been spending his nights recounting the Battle of Dan-no-ura to ghosts in the graveyard. They cover Hoichi’s body with holy text so the ghosts may no longer see him but have forgotten one place. In a Cup of Tea:- A writer pores over a series of unfinished texts that recount how several hundred years before Lord Nakagawa was haunted by a face staring out of every bowl of water he drank.

Ghost stories have a long and respected tradition in Japanese culture. The title of the film kaidan simply means ‘ghost story’ in Japanese (it is usually spelt kaidan but the title Kwaidan comes from a more archaic romaji – Anglicised spelling of the Japanese kana script). The tradition of the kaidan goes all the way back to the 17th Century in stage and folktales.

The kaidan was in particular popularised by Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904), an Irish-Greek writer who had travelled widely before settling in Japan in 1890. Working as journalist and teacher, he published sixteen books about various aspects of Japanese culture, several of these being about tales of Japanese folklore and ghost stories, which became of great fascination to Western audiences. The most famous of these was Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1903), published just before his death, which collects seventeen traditional ghost stories.

The kaidan enjoyed great success on the big screen in the 1950s where there was a huge international interest in Japanese cinema thanks to Akira Kurosawa. The so-called kaidan eiga enjoyed much popularity during this era with works such as Ugetsu Monogatari (1953), Ghost Story of Yotsuya (1959), The Ghosts of Kasane Swamp (1959), Jigoku (1960), Oni Baba (1964), Illusion of Blood (1965) and Kuroneko/The Black Cat (1968), among others.

Kwaidan uses the long-honoured portmanteau format and is not dissimilar in many ways to tv’s The Twilight Zone (1959-63) and the various Amicus anthology films around the same time beginning with Dr Terror’s House of Horrors (1965). (Indeed, the Snow Woman segment was later borrowed wholesale and without credit as one of the stories in Tales from the Darkside: The Movie [1990]). Kwaidan is also an attempt to tell horror stories from a specifically Japanese historical background. Despite the vast cultural differences between feudal Japan and the post-War America milieu of The Twilight Zone, it is surprising how similar many of the themes that run through these anthology stories are – the greedy and selfish receiving just desserts punishment, that any dabbling with the supernatural will cruelly come back to visit he who unwarily plays.

Director Masaki Kobayashi has a strong flair for the artistic – it is a genuine shame that he made no other genre films than Kwaidan for on display here is a talent that rivals that of Akira Kurosawa. All of the stories are set in the dynastic past, which is evoked with a command of cinematic artistry that is extraordinary. The film is conducted with a fascinated regard for formal ritual. The purpose of this is clearly one of contrast as when the supernatural does enter, its effect on established order is shattering – like in Black Hair with the long ritual of the wife welcoming the samurai home, which is then shattered by his shock discovery of her skeleton and descent into hysteria; or the scene in Hoichi the Earless where the nanny steps into the sea holding the infant emperor with dream-like and ritual slowness, followed by the remaining soldiers.

Kobayashi uses lighting schemes and colour contrasts with extraordinary effect – shooting twilights that are both yellow and pink, snowy skylines that are like giant whorls, even one sky that looks like a giant bird’s eye. The effect is the creation of a wholly fantastic world where one is never sure whether it is photographed or it exists inside a studio. In Snow Queen, Kobayashi manages to change from the everyday to the eerily otherworldly within the space of a single shot simply by changing the lighting from normal warm colours to an otherworldly blue reflected off actress Keiko Kishi’s white-painted face.

Hoichi the Earless is the finest of the stories – from its captivating recounting of the epic of the battle to the amazing images of the monks painting Hoichi’s body and the ghost warrior trying to find Hoichi, seen from his point-of-view as a blanked-out shape with only a pair of ears, to the shock ending. Snow Queen is also superb in its evocation of otherworldly mood. The other two stories are, although by no means poor, weaker in comparison. Black Hair is largely dependent on its twist ending so its effectiveness does not come until the end of the tale – it may have worked better as one of the middle segments rather than the opening. In a Cup of Tea suffers from the same problems that the writer in the story acknowledges – a lack of resolution.

In most cinematic release prints seen in the West in 1965, Snow Queen was cut and released as a separate short. (This was in order to reduce the film’s running time from three to a more commercial two hours). This is an odd artistic choice, considering that it is one of the best segments. Removing it leaves Hoichi the Earless bookended by Black Hair and In a Cup of Tea, which surely only weakens an otherwise exceptional film. The full film has however been restored for its video and dvd release.

Trailer here