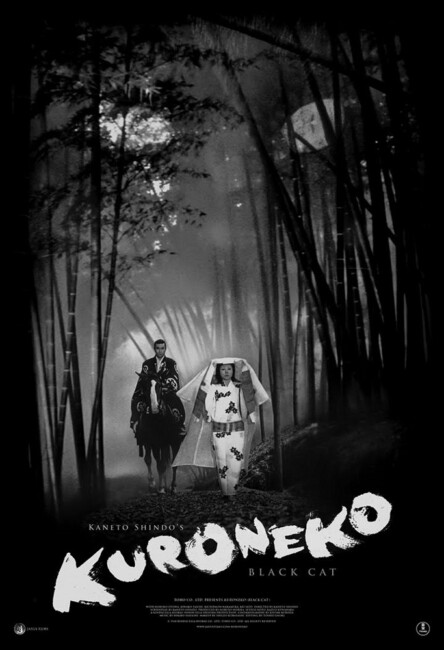

aka The Black Cat

Japan. 1968.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Kaneto Shindo, Producers – Nobuyo Horiba, Kazuo Kuwahara & Setsuo Noto, Photography (b&w) – Kiyomi Kuroda, Music – Hikaru Hayashi, Production Design – Norimichi Ikawa & Takashi Muromo. Production Company – Toho/Kindai Eiga Kyokai/Nihon Eiga Shinsha.

Cast

Kichiemon Nakamura (Gintoki of the Grove/Hachi), Nobuko Otowa (Yone), Kawako Taichi (Shige), Kei Sato (Raiko Minamoto), Rokko Toura (Samurai), Taiji Tonoyama (Jinbei)

Plot

Yone and her daughter-in-law Shige are living alone after their menfolk have been drafted to fight in the war. A horde of hungry samurai break into the house looking for food and then rape the two women and burn the house to the ground. Not long after, the two women appear to passing samurai at the Rajomon Gate, asking to be escorted home. They offer the men shelter at their house in the forest where they ply them with sake and then tear their throats out and drink their blood. The two women have struck a deal to be allowed to return as ghosts so that they can kill all samurai. The samurai master Raiko calls upon his best samurai to deal with the ghosts. Hachi has returned triumphant from a campaign in which all the other samurai were killed. Raiko gives him the new name Gintoki of the Grove and sends him to deal with the ghosts. Meeting the ghosts and being invited to their house, Gintoki is struck with how much they resemble the mother and wife he left behind, not realising that this is who they are. Shige is torn between her love for her husband and their vow to kill all samurai, which she realises must also include Gintoki.

The kaidan or Japanese ghost story has a long tradition that goes well back to the 17th Century. As a genre, it was popularised in printed fiction around the turn of the 20th Century by writer Lafcaido Hearn and others. The filmed equivalent, the kaidan eiga, emerged in the 1950s and 60s with works such as Ugetsu Monogatari (1953), Ghost Story of Yotsuya (1959), The Ghosts of Kasane Swamp (1959), Jigoku (1960), Kwaidan (1964) and Illusion of Blood (1965), among others.

Director Kaneto Shindo made one of the finest of these kaidan eiga with Oni Baba (1964), a story about two women living alone in the swamps who survive by killing samurai, which arrives at a particularly eerie supernatural twist ending. Both Oni Baba and Kuroneko show Kaneto Shindo as a director with an extraordinary grasp of cinematic style. Shindo was still alive and directing at the age of 98 before his death in 2012 at one hundred years old. His body of work, of which there is a substantial oeuvre (45 films between the 1950s and 2010), is something that has never been granted proper recognition.

Kuroneko, also known in English as The Black Cat, although no relation to the Edgar Allan Poe story The Black Cat (1843) or any of its film versions, is the particular sub-genus of the kaidan known as the bakemono (concerning shape-changing cats). In both Oni Baba and Kuroneko, Kaneto Shindo’s undeniable influence was the neo-realist school of Japanese cinema patented by Akira Kurosawa. In highly influential works like Rashomon (1950), The Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957), Yojimbo (1961) and Sanjuro (1962), Kurosawa placed an emphasis on historical spectacle, raw action and the abandonment of clean period settings to feature characters that are begrimed, muddy and frequently tattered. The neo-realist influence of Kurosawa and the Japanese New Wave clearly inspired Kaneto Shindo in both of these films. You can see it in the opening scene of Kuroneko, which is pure Kurosawa with its dramatically posed underlit closeups on the dirty faces of the samurai in their ragged clothing.

Kuroneko has a plot that is almost identical to Oni Baba at times – concerning two women living alone in an isolated area after their menfolk were recruited into the shogunate wars; their surviving by preying on and killing samurai; the two women being divided after the younger one wants to deviate from their mission for the sake of love. In both films, Kaneto Shindo uses the isolated surroundings – the sea of reeds in Oni Baba, the forest here – as an almost physical presence that takes on its own character. Of course, both films approach their supernatural element in different ways – Oni Baba is more of a mundane tale with a Twilight Zone (1959-63)-styled supernatural retribution twist in the ending, whereas Kuroneko has a very different arc that has the two women being ghosts from fairly much the start of the film.

Kaneto Shindo creates an exquisitely spooky film with Kuroneko – everything is shot in a beautifully high-contrast black-and-white. The initial scene where the samurai (Rokko Toura) is seduced is the film’s most dazzling set-piece – he is sleepily riding home past the Rojamon Gate on his horse when suddenly we momentarily see a figure that looks like a sheet or maybe a human being (it so brief we cannot be sure) conducting a silent acrobatic twirl over his head unnoticed. The effect is so abruptly out of this world that we are immediately at attention. The daughter-in-law (Kawako Taichi) then appears, claiming to be lost on her way back from a party and asks him to escort her home through the forest. The journey there is spookily otherworldly – there are the distant meows of a never-seen cat, the daughter-in-law appears to glide in slow-motion through the air over a puddle. They arrive at the house where the samurai is invited in for sake.

Things become increasingly more uncanny – the trees over the top of the house seem to move with their own life; the faces of the women with their unnaturally elevated kumadori eyebrows are all eerily underlit; as the camera focuses in on the samurai telling his story, he seems partially double-exposed over the background outside as though he is starting to become a ghost; and as she pours more sake, the daughter-in-law’s hand momentarily seems to be a cat’s paw. She then takes him to bed and predictably (and quite bloodily for the era) tears out his throat.

The rest of Kuroneko never quite sustains the same level of spookiness (at least until the end scene). The middle of the film moves away from the overt hauntings to become a drama where the three principals – samurai, his wife and mother – are torn between terrible choices – the women between their vow to the forces to Hell to kill all samurai, knowing that this too means the son; the wife between breaking their vows so she can enjoy her husband’s love once again; the samurai facing the threat of losing his own life if he does not eliminate the ghosts.

Kaneto Shindo brings the film together for a superbly haunted climactic scene – where the samurai has been ordered to spend seven days locked away in ritual purification; the mother lurks outside the house demanding her severed arm back; before there comes a knock at the door and the voice of a woman claiming to be the emperor’s seer demands to be let in, the samurai protests that he cannot break his vow and she threatens dire consequences to him and his master if he disobeys a request from the emperor; he lets her in but we cannot be sure if she is ghost or real, especially when she does not want to touch the altar and insists that he give her the severed arm. It is a scene where Kaneto Shindo does a superb job in keeping us hanging in a state of dread doubt about and uncertainty about what we are unable to see lurking outside.

Trailer here