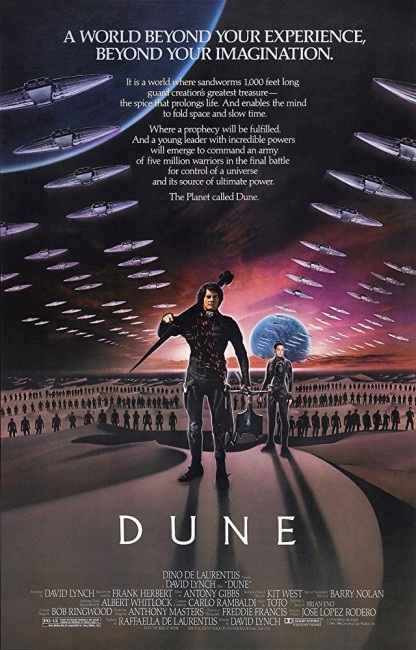

USA. 1984.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – David Lynch, Based on the Novel Dune by Frank Herbert, Producer – Rafaella De Laurentiis, Photography – Freddie Francis, Music – Toto, Prophecy Theme – Brian Eno, Photographic Effects – Barry Nolan, Additional Visual Effects – Albert Whitlock, Creatures – Carlo Rambaldi, Mechanical Special Effects – Kit West, Makeup Effects – Gianetto de Rossi & Christopher Tucker, Production Design – Tony Masters. Production Company – Dino De Laurentiis.

Cast

Kyle MacLachlan (Paul Atreides), Francesca Annis (Lady Jessica), Kenneth McMillan (Baron Vladimir Harkonnen), Jurgen Prochnow (Duke Leto Atreides), Everett McGill (Stilgar), Dean Stockwell (Dr Wellington Yueh), Sian Philips (Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam), Alicia Roann Witt (Alia), Sting (Feyd-Rautha), Brad Dourif (Pietr De Vries), Sean Young (Chani), Patrick Stewart (Gurney Halleck), Paul Smith (The Beast Rabban), Freddie Jones (Thufir Hawat), Jose Ferrer (Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV), Richard Jordan (Duncan Idaho), Linda Hunt (Shadout Mapes), Max Von Sydow (Dr Liet-Kynes), Virginia Madsen (Princess Irulan)

Plot

Political ripples are caused when the Padishah Emperor hands ownership of the planet Arrakis from the House of Harkonnen to their bitter enemies the Atreides family. Arrakis or ‘Dune’ is a desert planet and source of the all-important drug melange or ‘spice’, which is used by the Guild Navigators to warp space and travel from world to world. However, the move is a ruse and the Emperor sends his personal army to help the Harkonnens wipe out the Atreides. The Duke Leto is killed but his concubine Jessica and their son Paul escape into the desert and seek refuge amongst the native Fremen. Jessica, who belongs to the Bene Gesserit sisterhood that secretly manipulates the bloodlines of the empire, discovers that Paul is the messianic Kwisatz Haderach, the culmination of the sisterhood’s breeding program and that he can see into the future under the influence of the spice. With these powers, Paul is able wield the Fremen into an invincible army. Together they stop the production of spice upon Arrakis and bring the empire to its knees.

Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) is often called the science-fiction novel of the 1960s counter-culture movement, largely due to it having purportedly influenced Charles Manson. In truth though, the science-fiction novel that tapped into the essence of the 1960s and emerged with lasting impact was Frank Herbert’s Dune, first serialized in Amazing Science-Fiction between 1963-5, and winning most of the major awards in the science-fiction community upon its book publication in 1965

Dune is a work that crystallizes all the essential counter-cultural issues of the 1960s – environmental awareness, political protest (even acts of terrorism against established authority), mysticism, religion, drugs and altered states of consciousness, the embracing of alternate cultures. Dune was a work that author Frank Herbert would be forever associated with. Indeed, Dune became Frank Herbert’s bread and butter and he produced five book sequels – Dune Messiah (1970), Children of Dune (1976), God Emperor of Dune (1981), Heretics of Dune (1984) and Chapterhouse Dune (1985). Most of these are disappointing with Herbert having upped the Byzantine politics to the point the stories became obscure and frequently difficult to follow. However, the series was popular and are still being published today, carried on by Herbert’s son Brian following Herbert’s death in 1986 and then sharecropped out into a series of prequels by other writers.

The filming of such a complex and vaunted book was a daunting task that found the better of many. Roger Corman owned the rights at one point (one shudders to imagine what the film would have emerged like on a typical Corman budget). The most interesting of the planned productions was one that Alejandro Jodorowski, the cultish director of the bizarre likes of El Topo (1970), The Holy Mountain (1975) and Santa Sangre (1989), attempted to mount in 1976. This would have included such tantalising novelties as H.R. Giger, Chris Foss and Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud designing the look of the various worlds; Dan O’Bannon, later the screenwriter of Alien (1979), on special effects; a score from Pink Floyd; and such unique casting as Orson Welles as Baron Harkonnen, Mick Jagger as Feyd-Rautha and Salvador Dali in the role of the Emperor. The Alejandro Jodorowsky Dune is one that lives in legend – stories of it seem totally wild. Jodorowsky would have used the book only as a loose text and would have varied considerably from Frank Herbert – Jodorowsky’s Emperor was a madman who lived in a palace of gold at the centre of the galaxy with an exact robot duplicate; the film would have focused on the alchemical/mystical nature of Paul’s spice experience and the Bene Gesserit religion; and would have ended with Paul’s death and the transubstantiation of Arrakis into a force of consciousness that moves through the universe. Alas, Jodorowsky never found the funding for his idiosyncratic adaptation. There was a fascinating documentary made about this never-made version with Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013).

Dino De Laurentiis, the infamous producer of King Kong (1976) and Flash Gordon (1980), then bought the rights to Dune. De Laurentiis tried to mount a production with Ridley Scott, director of Alien and Blade Runner (1982), for a time then finally succeeded with David Lynch. At that point, David Lynch was a relative unknown who had made the midnight cult favourite Eraserhead (1977) and the more mainstream, critically acclaimed The Elephant Man (1980), which had had him nominated for a Best Director Academy Award. Following Dune, David Lynch would of course go onto make the likes of Blue Velvet (1986) also for Dino De Laurentiis, Wild at Heart (1990), Lost Highway (1997), The Straight Story (1999), Mulholland Dr. (2001), Inland Empire (2006) and the cult tv series Twin Peaks (1990-1) and its two theatrical spinoffs, Twin Peaks (1990) and Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), and make a name as one of the cultiest, most bizarre directors at work today. Dune was David Lynch’s first and last brush with big-budget studio-type film-making and Lynch has since publicly disowned the film.

All fans of the book lambasted the film when it appeared. Cult books tend not to make for successful films as they are viewed by a body of fans who are so familiar with the story they get finicky when small details are changed or their conception of the characters are not followed the way they think they should be. To get it over and done with, no, the film is not a successful adaptation of the book – by a wide margin. Dune was a film caught in an unenviable position – of being far too complex and challenging a story for audiences who were unfamiliar with the book to understand and invariably disappointing for those who had. The problem was not David Lynch’s own – he had originally envisioned a three hour plus epic but faced Universal who demanded that the final print only be two-and-a-half hours long. Lynch did not have Final Cut on the film and as a result was forced to sacrifice large sections of material that had been shot in order to bring the finished film in under the mandated time. Nevertheless, Dune remains a fascinating, even at times brilliant film. Certainly, it is not the disaster that David Lynch and many fans seem to think it is.

The first two thirds of the film is very faithful to the book. David Lynch does an excellent job of capturing all the intergalactic in-politicking and Frank Herbert’s ‘games within games’. However, it is the second half that disappoints. Lynch has cut out almost all the portrait of the Fremen and much of the messianic mysticism. The political holy war is reduced to a few brief war scenes. We, for instance, have no idea why the Fremen accept Paul Atreides as their messiah. Most disappointing, there is none of the fascinating immersion in a culture centred around desert survival and the scarcity of water that was one of the most interesting parts of the book. (There is a re-edited version that aired on tv in 1988 and is available on DVD, which contains some 40 minutes of footage unseen in the theatrical release. However, David Lynch objected to this version and substituted the generic Director’s Guild pseudonym Allan Smithee in lieu of his own). The film’s biggest miscalculation on the book may well be the ending. Lynch follows the book with the fate of the empire being decided in a duel between Paul and Feyd-Rautha but then throws in a mystical eucatastrophe where Paul’s political triumph is seemingly echoed by the entire planet, which seems to cheer him on by miraculously raining. It is a banal and unnecessary ending.

However, David Lynch may be incapable of making an entirely bad film. Dune tends to work best when Lynch gets the opportunity to conduct some freewheeling improvisations on Frank Herbert. The scenes Lynch seems to have the most relish for are the Harkonnen scenes. In the book, Frank Herbert merely left one with the suggestion that the Baron had paedophile tastes, but Lynch crafts the Harkonnen scenes with a much greater degree of grotesquerie than that. We are introduced to the Harkonnens in one wonderfully bizarre scene where Kenneth McMillan’s Baron sits being injected in his hideous facial sores by attendants in plastic macs, mirrorshades and sewn-shut cabbage ears, while Paul Smith sits drinking cocktails of squelched up insects, before the Baron rips out the throat of a hermaphroditic character and goes flying off through the open roof in his inflated longjohns maniacally laughing. There is a later thoroughly demented scene on Arrakis with Sting’s appearance, clad only in leather jockstrap and evilly smiling, while the Baron flies around a jet of steam at high-speed, all to the accompaniment of a wailing organ played by Eraserhead hero Jack Nance. All of which serves to add to a compulsively weird fascination.

Dune had a then-impressive budget in the neighbourhood of $40 million and it certainly shows up stunningly on screen. Dune was one of the few films in the post-Star Wars (1977), post-Alien, post-Mad Max 2 (1981) era to break away from the rundown technology look. Tony Masters creates a universe of art deco retro-futurism, filled with rococo technology – of steam carriages or communications devices that look like old radio microphones. Each of the worlds comes with a distinctive look – Caladan all brooding in deep woods, the fluted gilt piping of the Emperor’s palace, to the cavernous New Wave industrial nightmare world of the Harkonnen Giedi Prime. Dune is one of the most imaginatively designed of all science-fiction films.

The special effects are stunning. Carlo Rambaldi creates Frank Herbert’s sandworms with spectacular regard. The first appearance of a worm bursting out of the sand, crushing a spice miner in its jaws is dazzling. The climactic battle with Paul leading the Fremen into battle riding aboard hundreds of the giant sandworms takes the breath away in terms of scale. The most beautiful scene in the film – again one where David Lynch freely improvises on Frank Herbert – is the space travel sequence where we first follow tiny ships up off the planet and watch as they are dwarfed in scale as they enter the gilted door of giant orbiting cylinder and then once inside the giant spermatozoid Navigator moves up out of the cavernous gloom and warps the stars about it. It is a spectacularly beautiful moment of pure science-fictional beauty.

David Lynch also arraigns an impressively large cast. He casts a number of the actors he regularly works with – Freddie Jones, Everett McGill, Dean Stockwell, and of course Eraserhead‘s hero Jack Nance who appeared in all of David Lynch’s films until his death in 1996. (Lynch himself can be spotted in a brief cameo as one of the workers on the spice miner that is attacked by the sandworm). Kyle MacLachlan appears in the first of several distinctive and unique collaborations he would make with Lynch. Dune was also Kyle MacLachlan’s film debut and he brings his customary assured handsomeness to the role. The beautifully elegant Francesca Annis is well cast as Paul’s mother. Eight year-old Alicia Witt has strikingly evil presence as Paul’s younger sister Alia. [Witt would later gain attention as an adult actress with a recurring role as Cybill Shepherd’s daughter in the sitcom Cybill (1995-8) and in the slasher film Urban Legend (1998)].

Dune: Extended Edition

A longer cut of the film made for tv in 1988 and subsequently released to video as Dune: Extended Edition. This is a complete disaster. David Lynch disowned the work and substituted the generic Hollywood pseudonym Alan Smithee as director and that of Judas Booth when it comes to the script.

I watched Extended Edition around the same time as the director’s cut of Star Trek – The Motion Picture (1979). The latter is an example of how a director’s cut should be done, while Extended Edition is a perfect example of how it should not be. In the case of Star Trek, money and effort was expended to digitally fix and tidy up the visual effects shots. Here, by contrast, everything has been done cheaply. Many of the effects shots have been recycled throughout, while nobody has cared to go through and optically add blue eyes for the added scenes with the Fremen.

The worst part about the Extended Edition is the added prologue, which consists of some nine minutes of concept artwork for the film over which an unidentified narrator describes the background of the universe and the relation of the main houses to each other. The artwork brings down the quality of the rest of the film. Throughout we also get the addition of voiceovers that introduces characters. The introductory scenes also mean that Virginia Madsen’s Princess Irulan has been almost entirely dropped and appears only as a dialogueless character.

That said, the Extended Edition is not entirely an uninteresting film. It introduces a number of scenes that were cut from the theatrical release that serve to embellish and strengthen the story, taking it closer back to the novel. These include more scenes with the Emperor and Helen Mohaim at the start. Restored are key scenes from the book such as the scene where Dr Liet Kynes (Max Von Sydow) spits on the floor in the Fremen way to show his respect for the Duke; the fight between Paul and Jamis (a scene that was probably cut because it is not well directed) and of Paul then being gifted Jamis’s water after killing him; and the drowning of the worm to produce the water of life. All of the disastrous edits with the effects and the introduction aside, these scenes at least feel like a more full and satisfying telling of the book.

The book was later remade as Dune (2000), a tv mini-series made by director-writer John Harrison for The Sci-Fi Channel. This is a fine version and gives the book a much more substantial airing than this film does. The two make for interesting comparison. The mini-series has the greater running time to treat the book with much more scope and the severely curtailed Fremen scenes and messianic mysticism gets a much more complete airing here. The mini-series made an admirable depiction of Arrakis on its modest budget; on the other hand, the film version definitely has the more epic feel. Also the perversity that David Lynch invested the Harkonnens with makes for a much more interesting set of villains – Harrison never took the mini-series in that direction and Ian McNeice’s Baron seems decidedly wimpy. Harrison later wrote a further tv mini-series Children of Dune (2003), which adapted Frank Herbert’s second and third books in the series, Dune Messiah and Children of Dune. A further cinematic remake was posited throughout the 2010s before going ahead as a two-part film from Denis Villeneuve with Dune Part One (2021) and Dune Part Two (2024).

David Lynch’s other films are Eraserhead (1977), The Elephant Man (1980), Blue Velvet (1986), Twin Peaks (1990), Wild at Heart (1990), Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), Lost Highway (1997), The Straight Story (1999), Mulholland Dr. (2001) and Inland Empire (2006). Lynch also created and directed many episodes of the cult tv series Twin Peaks (1990-1, 2017). Lynch has also produced other genre films such as The Cabinet of Dr Ramirez (1991), Nadja (1994), Surveillance (2008), My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done (2009) and Black and White in Colors (2010), as well as two short-lived surrealist tv series with On the Air (1992) and Hotel Room (1993). Lynch (2007), David Lynch: The Art Life (2016) and Lynch/Oz (2022) are documentaries about Lynch.

Trailer here