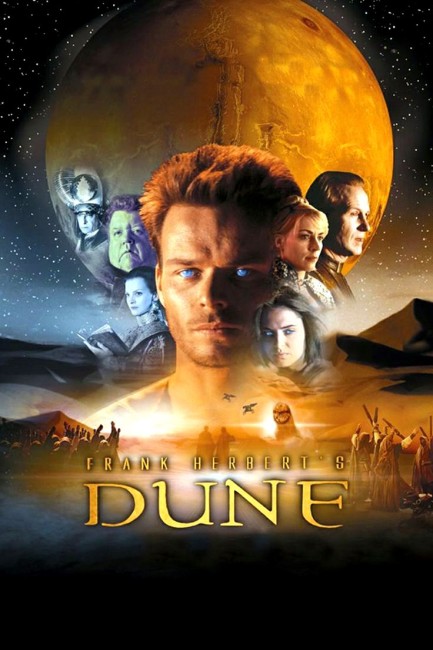

USA. 2000.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – John Harrison, Based on the Novel Dune by Frank Herbert, Producer – David Kappes, Photography – Vittorio Storaro, Music – Graeme Revell, Visual Effects Supervisor – Ernest Farino, Visual Effects – AI Effects Inc (Supervisor – Frank Isaacs), Area 51 (Supervisor – Tim McHugh), Flat Earth Productions Inc & Netter Digital Entertainment (Supervisor – Laurel Klick), Stop Motion Animation – Chiodo Brothers Productions Inc, Special Effects Supervisor – Jim Healy, Production Design – Miljen ‘Kreka’ Kljakovic. Production Company – New Amsterdam Entertainment Productions/Victor Television Productions Inc/Evision.

Cast

Alec Newman (Paul Atreides/Muad’Dib), Saskia Reeves (Lady Jessica), Uwe Ochsenknecht (Stilgar), Barbora Kodetova (Chani), Ian McNeice (Baron Vladimir Harkonnen), William Hurt (Duke Leto Atreides), Julie Cox (Princess Irulan), Matt Keeslar (Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen), Giancarlo Giannini (Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV), R.H. Moriarty (Gurney Halleck), Zuzana Geislerova (Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohaim), Laszlo Imre Kish (Rabban), Karel Dobry (Dr Liet-Kynes), Laura Burton (Alia), James Watson (Duncan Idaho), Drahomira Fialkova (Reverend Mother Ramalla), Robert Russell (Dr Wellington Yueh), Jaroslava Siktancova (Shadout Mapes), Christopher Lee Brown (Jamis)

Plot

The Padishah Emperor places the Atreides family in charge of the desert planet Arrakis, known informally as Dune. Arrakis is source of the all-important chemical spice, which is used by the Guild Navigators to travel through space. This move is deeply resented by the Atreides’ sworn enemies The House of Harkonnen. On Arrakis, the Duke Leto Atreides’ son Paul becomes fascinated with culture of the native Fremen, which is based around survival in the harsh desert conditions. Baron Harkonnen launches an elaborate plot to bring about the Atreides’ downfall. The Baron reoccupies Arrakis with his armies and slaughters the Atreides with the assist of a traitor within their household. Paul and his mother Jessica, a member of the matriarchal Bene Gesserit religious order, flee into the desert and take refuge among the Fremen. Under the influence of spice, Paul begins to discover his abilities to see the future and realises that he is the long sought-after Kwisatz Haderach that the Bene Gesserit have long manipulated the bloodlines of the empire in an effort to produce. Taking the name of the desert mouse Muad’Dib, Paul organises the Fremen into a powerful fighting force and sets out to bring down the Harkonnen occupation by sabotaging the all-important spice production.

Frank Herbert’s novel Dune (1965) is an undisputed classic of science fiction literature. Dune almost invariably tops the list among readers 2-3 favourite works of science-fiction literature. Author Frank Herbert (1920-86) trained as a journalist and began publishing science-fiction in 1952. Dune emerged out of an article that Herbert was assigned to write in the late 1950s on the ecology of sand dunes in Oregon. In researching the subject, Herbert became so fascinated with the surrounding issues that he gained far more background research than he could ever use in an article. This evolved into Dune, which was first published in the science-fiction magazine Analog as two shorter serialised novellas, Dune World (1963-4) and The Prophet of Dune (1965), and then in book form.

The book crystallizes the many concerns that run throughout Herbert’s fiction – the future evolution of humanity, the flawed nature of the superman, and in particular the concerns with environmentalism, a subject that Frank Herbert later wrote non-fiction articles and lectured about. (For Herbert, the battle over spice was a metaphor for oil). Dune throws these together in a plot that draws inspiration from Roman history and the character of Lawrence of Arabia, the charismatic figure that drew Bedouin tribes together to fight during World War II. Dune is a sweeping work that can only be compared in the breadth of scope and complexity of its cultural-historical background to J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (1954-6).

The book won all of the science-fiction community’s major awards the year it was published. Frank Herbert spun out a series of sequels of lesser but not entirely unworthy effectiveness – Dune Messiah (1969), Children of Dune (1976), God Emperor of Dune (1981), Heretics of Dune (1984) and Chapter House Dune (1985). Subsequent to Frank Herbert’s death in 1986, the series has been sharecropped into a series of routine prequels by Herbert’s son Brian. There have also been all manner of Dune spinoffs, including both computer and board games (there are few other works of written science-fiction that can make that claim). None of Frank Herbert’s other books ended up standing up there alongside Dune – Herbert has highly articulate ideas but the drawback of his writing is that these often come presented in the midst of excessively complicated plots that do not always make for easy reading.

A film version of Dune had been planned for a number of years. In the mid-1970s, Alejandro Jodorowsky of El Topo (1970) fame planned a fascinatingly bizarre adaptation from a script by Dan O’Bannon and with designs by H.R. Giger, although this adapted the book very freely. (Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013) is a documentary about the production that never happened). Producer Dino De Laurentiis then inherited the rights and planned a version with director Ridley Scott. However, the complexity of the work – both in terms of the extraordinarily Byzantine convolutions of Frank Herbert’s plotting and counter-plotting and the number of themes that the book broaches (environmentalism, alien culture, politics and a kind of intergalactic I, Claudius) proved daunting. A film version did finally emerge directed under David Lynch with Dune (1984). Although universally regarded as a disappointment in terms of the book, the David Lynch film is a not entirely uninteresting effort. If it is a failure, then it is certainly a fascinating one that holds some visually stunning moments.

This six-hour tv mini-series remake of Dune was one of a host of adaptations of science-fiction literary classics that were commissioned by the US-based Sci-Fi Channel, along with other works like Riverworld (2003) and Earthsea (2004). The mini-series was made by Richard P. Rubinstein, the former producing partner of George Romero, and his New Amsterdam Entertainment production company. Rubinstein has placed the adapting and directing chores in the hands of John Harrison. John Harrison first gained his break working as an assistant director and an actor in minor parts in various Romero films – he was the zombie that got a screwdriver in his ear in Dawn of the Dead (1978) – and then graduated to composing the scores for Creepshow (1982) and Day of the Dead (1985). Harrison made his debut as a director on the Romero-Rubinstein produced Tales from the Darkside horror anthology series (1984-6) and then went onto make his first feature film with the fine and underrated Tales from the Darkside: The Movie (1990). Harrison worked sporadically in series television throughout the 1990s, with his most notable credit being co-writing the script for the animated Disney film Dinosaur (2000). Subsequently, Harrison went onto direct the disappointing disaster mini-series Supernova (2005) and the Clive Barker adaptation Book of Blood (2009).

David Lynch’s version of Dune was driven by a flamboyant visual ostentation; by comparison, this production is much more modest. In fact, John Harrison’s unassuming approach is something that brings the strengths of the book out rather than tends to act as a Reader’s Digest Condensed Version as the Lynch film did. All of the elements – from the Fremen culture to the complexities of the politics – are there and granted fair time on screen. Harrison brings out incidents in the book – the sandworm devouring the miner, the Hunter-Seeker entering Paul’s bedroom and so on – and makes them dramatically enthralling set-pieces, while also anchoring them within the plot.

Certainly, Harrison has made a number of changes to the book. The most apparent of these is in turning both Feyd-Rautha and Princess Irulan into much more central characters, whereas in the book they tended to be peripheral figures, only coming into their own at the very end. Both have been made stronger characters in the series, particularly Irulan (played by the bewitchingly lovely Julie Cox) who is shown as more of a schemer and much more politically astute than Frank Herbert had her. The dramas involving the two of them (and Paul) also function as a mini stage at the forefront of the story – one that is essentially played out by the children of the three houses – for the grander conflicts of the families in the background.

John Harrison also spends a good deal of time elaborating out the scenes with the Fremen and detailing the ecological themes, a side of the book that David Lynch glossed over. We get a genuine sense of a living, breathing alien culture on screen. On the minus side, Harrison for some reason downplays the Bene Gesserit as characters – Zuzana Geislerova’s Reverend Mother holds little in the way of threat (even less when compared to Siân Phillips fine performance in the David Lynch version) and little time is given over to the sisterhood’s machinations. Harrison also makes no mention of Frank Herbert’s concept of Mentats, humans that came to replace computing machines in his anti-technological future, nor is there any mention of the employment of nuclear arms by the Atreides to win their climactic battle.

Nevertheless, all told, John Harrison does a surprisingly strong, dramatic, coherent and above all faithful job of bringing Dune to the screen. The 1984 film has the edge in terms of spectacle and design but John Harrison’s version is almost certainly the better as an adaptation of the book and the more coherent as an overall story.

The designers make a concerted effort to get away from association with Lynch’s Dune with occasionally ungainly results. The Guild Navigators appear only briefly and look weak in comparison to the fabulous space warping sequence that Lynch gave us. The costume designers go wild, creating some at times bizarre creations – the Bene Gesserit wear headgear that seems to enwrap the head in giant silken seashells; Feyd-Rautha has an enormous triangle seated on the back of his costume behind his neck; while Princess Irulan goes through a mind-boggling series of changes, at one point wearing a dress with plastic butterflies woven into the material.

The sets both make a conscious effort to get away from the distinctively styled worlds of the David Lynch version, although ultimately fairly much end up following the same design schemes. Nevertheless, there is an elegant beauty to the sets. Giedi Prime comes all in angular Byzantine reds and bronzes; the Emperor’s homeworld Secusa Secundus has a blue-drenched Florentine look; while the Fremen scenes are designed with a fascinating mixture of traditional Arabic designs and modern technology.

The series cut location costs by avoiding going out into the desert to shoot by instead building a desert on a soundstage in the Czech Republic with piles of sand and a series of giant painted backdrops. The backdrops are occasionally obvious but the lighting and colour schemes employed also lend a beautiful abstract quality, particularly during Paul and Jessica’s journey across the desert during the middle episode. (It is hard to think of any other works of filmed science fiction where the lighting scheme plays such an integral part in the creation of an alien world. John Harrison also conducted striking lighting schemes in Tales from the Darkside: The Movie).

The effects do not have the budget available that David Lynch did, although the one thing that John Harrison does have on his side in between the time the two versions were made is the advent of CGI. The effects team do some superb work. The first appearance of a sandworm, blasting out of the sand and opening its giant maw and the struggle of the Duke’s ornithopter to escape being sucked in as the worm devours the sandminer is a stunningly good set-piece that is as fine as anything in the 1984 version.

Perhaps the most disappointing aspect of the mini-series is the casting of Ian McNeice as Baron Harkonnen. McNeice gives us the Baron as a prissy champagne villain who lacks in any real threat or cruelty, at most demonstrates a preference for young boys. In Ian McNeice’s performance, we have a jolly and overweight upper-class British man floating around who demonstrates little in the way of the deviously calculating intelligence and depraved perversity that we saw in the book or Kenneth McMillan’s entertainingly broad performance in the David Lynch film. Another disappointment is Saskia Reeves’ Lady Jessica. Saskia Reeves gives an okay performance but rarely one that seems to hold the mystery and elegant presence that the character did on the page and particularly in Francesca Annis’s striking portrayal in the 1984 film.

On the plus side, Scottish actor Alec Newman is excellent as Paul Atreides. Harrison and Alec Newman give us a character who evolves with subtle regard throughout the course of the series – from the brash but intelligent youth we meet at the start to the charismatic messiah following a vision that lies beyond this horizon that we come to see by the time of the third part – and Newman rises to fill the requirements of the role with considerable strength.

One of the strong points of the series is also the lovely Julie Cox, who makes an elegantly beautiful Irulan and imbues the character with a sharp intelligence, bringing her to life far more so than Frank Herbert ever did. John Harrison has also cast many of the supporting roles, particularly those of the Fremen, with non-native English speakers (German and Czech), where the accents have an unusual alienating effect. The performances from Uwe Ochsenknecht as Stilgar and Barbora Kodetova as Chani are particularly good here – he projecting a considerable dignity and she a haughty strength.

John Harrison (only writing the script this time) and most of the cast later returned for a sequel, Children of Dune (2003), which actually combines Herbert’s two subsequent book sequels, Dune Messiah and Children of Dune. A further cinematic Dune remake was posited throughout the 2010s first by directors Peter Berg and Pierre Morel, before going ahead as a two-part film from Denis Villeneuve beginning with Dune: Part One (2021) and Dune Part Two (2024).

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 2000 list. Winner for Best Adapted Screenplay, Nominee for Best Actor (Alec Newman), Best Supporting Actress (Julie Cox), Best Special Effects and Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 2000 Awards).

Trailer here