Crew

Director – Nick Hamm, Screenplay – Mark Bomback, Producers – Marc Butan, Sean O’Keefe & Cathy Schulman, Photography – Kramer Morgenthau, Music – Brian Tyler, Special Effects Supervisor – John LaForet, Mechanical Effects – Louis Craig, Production Design – Doug Kraner. Production Company – Lions Gate Films/Artists Production Group/2929 Entertainment.

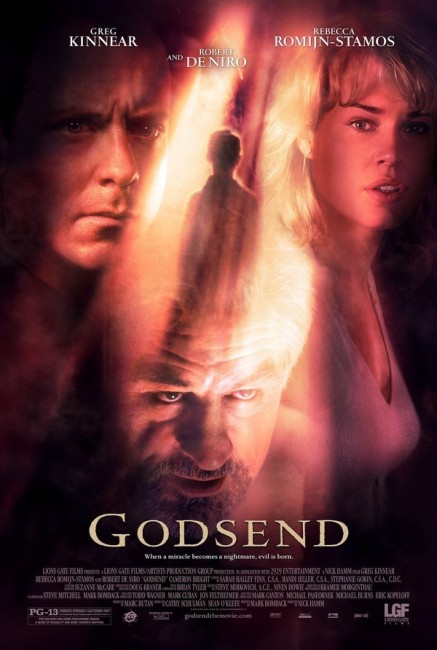

Cast

Greg Kinnear (Paul Duncan), Rebecca Romijn-Stamos (Jessie Duncan), Robert De Niro (Dr Richard Wells), Cameron Bright (Adam Duncan), Janet Bailey (Coral Williams)

Plot

Paul and Jessie Duncan are shattered when their eight year-old son Adam is killed by a skidding car. Immediately after the funeral, they are approached by Dr Richard Wells who tells them that he is a fertility specialist and has the capacity to bring Adam back to life by cloning. Paul is outraged by the idea but Jessie brings him around and they agree. Wells requires them to leave their life in New York City behind and move into a house he has provided near his clinic. Jessie is impregnated with a cloned cell and successfully gives birth. The Adam clone grows up a perfectly natural child. Eight years later, as Adam approaches the age when the original Adam was killed, he is plagued by nightmares and a troubling sleep disorder. Wells insists that this will pass but Paul and Jessie become concerned as the nightmares instead increase and Adam appears to be haunted by the ghost of a child named Zachary. At the same time, Adam becomes increasingly colder in personality and may even be responsible for the death of another boy.

Godsend is a film about cloning. It has been made with A-budget production polish and has even managed to reign in the great Robert De Niro to play a fertility specialist. It was the first film in the US mainstream for British director Nick Hamm, who previously made the psycho-thriller The Hole (2001) and subsequently went on to the non-genre Killing Bono (2011) and The Journey (2016).

While it has arrayed a line-up of talent that cannot be faulted, Godsend is a disappointing film. The exercise is sunken by a script that is contrived and manipulative to the point that it makes you want to thump the filmmakers at the transparency of the wool they are trying to pull over one’s eyes. For its first half-hour, Godsend passes unremarkably. Here one is prepared to buy it as an earnest feelgood drama about cloning that has been pitched on about the level of the average tv movie.

The greatest amusement during these scenes is in noting just how much the cloning institute portrayed differs from such organisations in real life. Indeed, the film’s Godsend Institute and the one other company in the world that claims to be practicing cloning at the moment – Clonaid, the offshoot of the Raelian sect – seem almost entirely reversed in their methods and ambitions. Godsend has Robert De Niro’s Dr Wells operating in secrecy and having to beg a couple to take place in his experiments, even being prepared to outfit them with a house near his clinic in order to have his experiment go through; in reality, Clonaid and the Raelians, while they do operate in secrecy, have held press conferences and openly advertised to the extent that they are being overwhelmed by requests from couples wanting children genetically resurrected. Moreover, rather than eagerly begging people to participate and offering to set prospective clients up in houses, the Raelians charge some hundreds of thousands of dollars for services that they have yet to demonstrate work (at least beyond their own self-promoted claims that they have succeeded, claims that have also been viciously attacked by all those conducting open, peer-reviewed research in the academic world).

After starting out as a painfully earnest drama about cloning, Godsend takes a rapid dogleg turn and suddenly becomes a ghost story. This is where the film starts to become frustratingly manipulative, not to mention incredibly bogus. The script, despite earlier attempts to ground itself in credible genetics, soon leaves plausibly extrapolated science behind to enter the realms of the ludicrous. As its various revelations are unveiled, the script increasingly starts to makes no sense whatsoever.

[SPOILER ALERTS]. Initially we are given the hokey notion that when the cloned child reaches the age when its predecessor died, it is not known what might happen. There is no scientific grounding for such an idea – it is like claiming that if a child died and then the parents had another child that the second child might suddenly experience similar things to the first child or have flashbacks as it reached the age when the original died. (A clone is nothing more than a child that has the same genetic material as another – in other words, a twin that was not born at the same time).

This is supposedly justified by a speech that Robert De Niro gives where he quotes the experiment where rats were run through a maze, ground up and then fed to other rats that had never run the maze but inherited knowledge of the maze from eating their brethren. Alas, the script gets it wrong – the experiment conducted in 1955 by Robert Thompson and James V. McConnell was done with earthworms, not rats, for one – and fails to mention that the results were later discredited. Even so, it is a long stretch to go from even the dubious notion that memory can be inherited from devouring another person’s ground-up brain cells to saying that these memories can be inherited from a single cell.

After setting this notion up, the film happily misleads us into thinking that as the clone child reaches his eighth birthday (when the original died), he is being haunted by the spirit of the original. Nick Hamm certainly produces some adequate jumps during these sections. However, this is only the first of Godsend‘s blatantly manipulative misdirections, where it later becomes apparent that this is not a haunting at all, despite the film making every effort to convince us it is, but in fact inherited memories coming through. Yet even after this is revealed, the film annoyingly still maintains the ghost story fiction in order to get another jump in just before the lights finally come up.

[SPOILERS CONTINUE]. Eventually it is revealed that what is going on is that Robert De Niro’s fertility doctor has not cloned their son at all but has recreated his own psychopathic dead child. At no point are we ever given any credible type of establishing motivation as to why De Niro is so obsessed with the notion of bringing back to life such a bad, murderous child. However, the biggest plausibility hole the film has is simply this:– if it was DNA from Robert De Niro’s child that ended up being implanted in Rebecca Romijn-Stamos, then how does the child comes out resembling their dead son? If it was De Niro’s child’s DNA that was implanted in Romijn-Stamos’s cell, then there would be no DNA whatsoever of their own child.

Moreover, again a function of the script’s blatant manipulations, if the child was De Niro’s son, why would its personality seemingly be invaded by the memories of the dead child? It would surely simply be the dead child recreated, not a schizoid mix of two children. One of the funniest moments in the film comes right at the end when the bad clone child is right on the verge of attacking the two parents in a shed but instead drops his evil glare and comes into their arms, defying his genetic inheritance, because well … no other real reason than that the story has reached an end.

In the end, what we have is yet another Frankenstein science film that has taken an issue of topical interest from the headlines and grafted a wildly histrionic reaction to it. The film is no different in tone from the ill-informed public hysteria that wants cloning, genetic engineering and the quite beneficial issue of stem cell research banned on the grounds that it is killing unborn souls or that it might produce races of three-armed mutants. The climactic confrontation that comes between outraged father Greg Kinnear and Robert De Niro, spouting dialogue that has been copied from every mad scientist cliché, notedly takes place in a church, which De Niro symbolically sets fire to before departing. Such heavy-handed symbolism says all there is to about where Godsend is coming from – it is not even a scientific examination of an current affairs topic, it is a horror story with a conservative Christian agenda masquerading as topical science. Things were even more bizarrely to the point in Blessed (2004), a copy of Godsend the same year, wherein the child that Heather Graham becomes pregnant with at a fertility/cloning centre turns out to be The Antichrist.

Perhaps the most amusing thing that Godsend will ever be remembered for is its novel marketing strategy. As part of the film’s promotional campaign, Lions Gate set up a website (www.godsendinstitute.org) and even a 1-800 number for the film’s fictional Godsend Institute, which posed as a genuine corporation offering to genetically resurrect the dead. The site amusingly contains fake bios for De Niro’s Dr Richard Wells and even eligibility tests that prospective clients can fill out. The studio then found themselves in an embarrassing position when people started genuinely responding to the promotion wanting to know if they could have their children brought back and had to alter the advertising to tell people that the site was only promoting a movie.

Godsend is unrelated to and should not be confused with the British evil child film The Godsend (1980).

Trailer here