UK. 1963.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Peter Brook, Based on the Novel by William Golding, Producer – Lewis Allen, Photography (b&w) – Gerald Feil & Tom Hollyman, Music – Raymond Leppard. Production Company – Allen Hodge/Two Arts.

Cast

James Aubrey (Ralph), Hugh Edwards (Piggy), Tom Chapin (Jack), Tom Gaman (Simon), Roger Edwin (Roger)

Plot

As nuclear war threatens England, a planeload of boys are evacuated from a public school but the plane is shot down over the Pacific Ocean. The boys wash up on the shores of an uninhabited island. One boy Ralph finds a conch shell on the beach and uses it to call the others together. They set up a nominal society, with Ralph being voted the leader. Ralph creates a set of rules to organise themselves until they can be rescued, including keeping a bonfire burning to signal passing ships and planes. The society is soon threatened by Ralph’s rival, the charismatic Jack, who creates his own group of Hunters to find food. Jack’s appeal to the thrill of hunting pigs and holding feasts soon draws all the other boys away from trying to maintain order and the bonfire is abandoned. This causes the society to fracture into two groups. The Hunters fear a beast that some of the boys believe is lurking on the island. Jack whips this into a frenzy, convincing them that Ralph and his remaining handful of survivors are The Beast and sending the boys to hunt them.

Although it did not enjoy much success when it initially came out, William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies (1954) has become regarded one of the great works of 20th Century literature. It is widely studied in schools – this author can remember doing so back in his teens. What makes Lord of the Flies such a classic is that it is a parable about the thin veneer separating civilisation from barbarism. The story works as a microcosmic allegory that allows a great many things to be read into it. Although, what it reads as most of all today is as an argument for British traditionalism – that that which holds society together is those doing the quietly dutiful and responsible things, while the elements of barbarism (which are so broadly sketched they can be read as an allegory for Nazism, colonial Africa under British Empire or just simply mob rule) that bay at the door and appeal to the primal aspects of human nature must be fought at all costs.

By the time this film version was made, the story had attained an additional level of subtext – the fear of imminent nuclear war, as seen in the montage at the start of the film. In 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis had had the whole world on the brink of nuclear Armageddon. With the film being made just after that it is hard not to see the society that Ralph is trying to hold together is just as much one that he is holding at bay from the fear of nuclear annihilation.

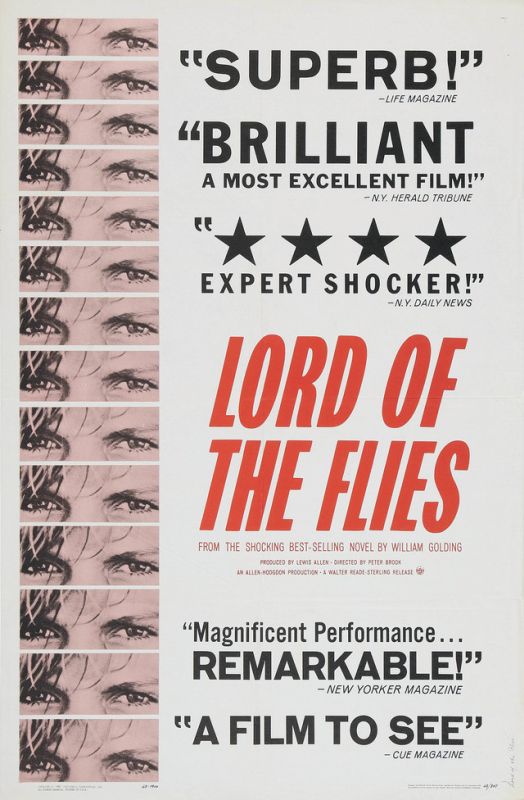

Lord of the Flies was taken up as a project by British theatre director Peter Brook, who had gained fame for his operas and stage productions for the Royal Shakespeare Company. Peter Brook had previously ventured onto film as director with Moderato Cantabile (1960) and went onto later works like The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum at Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (1966) and Meetings with Remarkable Men (1979). Peter Brook’s one other venture into fantastical material was The Mahabharata (1989), a six-hour tv mini-series based on the epic Indian poem and Hindu holy text. Brook shot Lord of the Flies on location in Jamaica and Puerto Rico with a cast of children who had had no prior acting experience.

Peter Brook has taken flack from admirers of the book for his claimedly liberal adaptation. Although going by my admittedly rusty school day readings, he keeps close faith to the story and I am unable to remember any aspects of the book that have been substantially curtailed. A read around of various other commentators on the web cites only things like the way some of the boys’ look as being different to the way they are described in the book, which are relatively minor matters when it comes to adapting a work to the screen. Certainly, if you compare Lord of the Flies to Peter Jackson’s massively popular Lord of the Rings, Jackson take much more sweeping liberties with the text than Peter Brook does here. The naysayers about this version, which keeps to the essence of the book and certainly does not elaborate any scenes beyond what is already in the text (aside from the minor addition of the mention of nuclear war at the start) obviously have not seen the disastrous American remake (see below).

Rather than most commentators, I would contend that Lord of the Flies (within the usual liberties that one extends to a film adaptation) is a literate and even brilliant adaptation. At every turn, Peter Brook captures the ferocity and fascination of William Golding’s symbols and metaphors – it is rare to see a film work on such a complex level of allegory. The times when Brook puts William Golding’s words and the observations of events bigger and beyond the understanding of the boys into their mouths, the film works with frightening effect.

The black-and-white photography adds stark impact. The big dramatic scenes – the hunting and hungry devouring of the pigs, and particularly the frenzied firelight dance wherein one boy is mistaken for and hunted as a monster – have a ferocity and starkness that fully conveys that primality of what William Golding intended with the Hunters. Indeed, in depicting this visually, Peter Brook does a far better job than Golding did with these scenes, limited as he was by the nature of the printed page. For its time, Lord of the Flies is unexpectedly graphic in tone and surprisingly uninhibited about portrayals of male (albeit adolescent) nudity. The film works just as effectively in its moments of quiet dialogue – where Peter Brook fully conveys the horror of civilised order slipping away in scenes like where the two young boys start to forget their carefully rehearsed phone number or the scary justifications that Piggy starts to offer to dismiss the killing of Simon.

A frequent criticism made of the film is how the children seem stilted. Initially, they appear as though delivering their lines by rote, but when the film settles in most of these are surprisingly good performances. Best of all is Hugh Edwards as Piggy, who makes the most out of a pivotal role – the moment where he tells a silly little story about how his hometown received its name shows a masterful evocation of the idiosyncratic lilt and accent of regional voicing. His dialogue holds some haunting commentaries.

In his autobiography The Shifting Point (1987), Peter Brook made the sobering comment: “People always ask whether the children understood and what effect it had on them … My experience showed me that the only falsification in Golding’s fable is the length of time the descent to savagery takes. His action takes about three months. I believe that if the cork of continued adult presence were removed from the bottle, complete catastrophe could occur within one long weekend.”

The William Golding book was later remade as Lord of the Flies (1990), which turned the English schoolboys into a group of students from an American military academy and seemed to have no grasp of William Golding’s swim of allegories. There was purportedly also an uncredited Filipino adaptation of the story made in 1975. In the arena of bad ideas, a further Lord of the Flies remake was announced in 2017, which would be told as an all-girl version. This has yet to emerge however there was the SF film Voyagers (2021) that relocated the story on a spaceship.

Lord of the Flies has been William Golding’s most famous novel. He has wrote a number of other works that sometimes touched on genre material, in particular The Inheritors (1955) about the last tribe of Neanderthals coping with the rise of homo sapiens, and Pincher Martin/The Two Deaths of Christopher Martin (1956), which prefigures the deathdream cinematic cliche – see An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge (1961) – in its tale of a castaway on a desert island. Other (non-genre) Golding works to be adapted to screen include the BBC mini-series To the Ends of the Earth (2005) about a 19th Century sea journey to Australia.

Trailer here