USA. 1974.

Crew

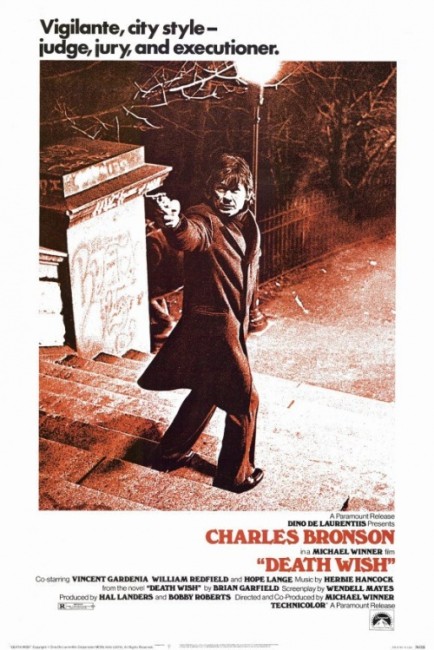

Director – Michael Winner, Screenplay – Wendell Mayes, Based on the Novel by Brian Garfield, Producers – Hal Landers & Bobby Roberts, Photography – Arthur J. Ornitz, Music – Herbie Hancock, Makeup – Phillip Rhodes, Production Design – Robert Grundlach. Production Company – Dino De Laurentiis Corporation.

Cast

Charles Bronson (Paul Kersey), Vincent Gardenia (Lieutenant Frank Ochoa), Hope Lange (Joanna Kersey), Steven Keats (Jack Toby), Stuart Margolin (Aimes Jainchill), William Redfield (Sam Kreutzer), Kathleen Tolan (Carol Toby)

Plot

Architect Paul Kersey’s wife Joanna returns from the supermarket followed by three petty hoods who force their way into the apartment where they brutalise Joanna and rape his daughter Carol. Joanna is killed and Carol left so traumatised that she has to be placed into an institution. Afterwards, Kersey sees only rampant lawlessness and crime all around him. After a client gives him a revolver as a gift, Kersey starts to walk the New York streets carrying it and then shoots the first person that tries to mug him. He begins a spree of vigilante killings, making himself into a target and then shooting the muggers that attack him. This has the unexpected result of bringing muggings in the city down and inspiring the citizens to stand up against petty criminals everywhere. The police are baffled and do not know whether they should stop Kersey or applaud his efforts.

Before the 1960s, the concept of the hero was fairly black-and-white. The hero’s most popular medium was in The Western. There the hero, usually embodied by John Wayne, stood up for what was right and decent, was usually on the side of law and order or fighting to tame lawless elements of the wild frontier. The villain was equally clearcut – in fact, many Westerns made the issue clear by having the hero in a white hat and the villain in a black hat. By the late 1960s however, classic heroism was starting to slip. Clint Eastwood led the way with his Spaghetti Westerns, which depicted the hero as a loner who operated according to his own code and frequently killed. And then there was Dirty Harry (1971) and sequels, which took the detective hero into decidedly grey moral areas – Dirty Harry was a loner who wiped scum off the streets and expressed contempt for the lily-livered bureaucrats who created rules that allowed the guilty to go free. Eastwood’s Dirty Harry and Charles Bronson’s Paul Kersey here fairly much created the action movie hero between them – gun-toting anti-heroes who fought according to their own notion of what was right, were not afraid to take on vastly outnumbered forces and exacted swift and brutal justice at the end of a gun barrel.

Death Wish was also the point when Charles Bronson began to become a screen presence (you could hardly call Bronson an actor). Bronson had been working steadily as an actor since the 1950s and began to earn a name for himself following a supporting role in The Magnificent Seven (1960). He appeared throughout the 1960s in films like The Dirty Dozen (1967) and especially found employment in Italy in a host of Spaghetti Westerns, the most well known of these being Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Bronson came into his own back in the US in the early 1970s in crime films such as The Mechanic (1972), The Valachi Papers (1972) and The Stone Killer (1973), although it was Death Wish that made him a star. For the next decade-and-a-half after Death Wish, Charles Bronson would find himself typecast in these vigilante avenger roles in films like 10 to Midnight (1983), The Evil That Men Do (1984), Murphy’s Law (1986), Assassination (1987), Messenger of Death (1988) and Kinjite: Forbidden Subjects (1989), as well as four Death Wish sequels.

Death Wish was made by Michael Winner. Michael Winner is a director who has a bad reputation – Tim Healey’s The World’s Worst Movies (1986) devotes an entire chapter to Winner’s oeuvre. Winner emerged in England in the 1960s with various nudies and trendy Swinging 60s comedies, before being invited to the US by Death Wish producer Dino De Laurentiis to make the Western Lawman (1971). Winner had previously worked with Charles Bronson on the Western Chato’s Land (1972) and then The Mechanic, which many regard as Bronson’s best film. Winner has made a number of entries that venture into genre material with the Turn of the Screw prequel The Nightcomers (1971), the occult horror The Sentinel (1977), the psycho-thriller Scream for Help (1984), the amazingly sordid gun-toting vigilante chick flick Dirty Weekend (1992), and Parting Shots (1999) where a dying man sets out to eliminate those who made his life miserable.

Death Wish is a film rooted in 1970s urban anxiety. This was a decade when middle-class people in large cities suddenly began to become afraid of the lawlessness they saw around them – Death Wish even starts quoting urban crime statistics within its first few minutes of screen time. The background of the film is filled with images of urban disorder or indifference – Charles Bronson seeing random attackers from out his window or in the background at railway stations, people complaining about being made to wait at hospitals and police stations. The muggers that we see throughout are characterised as evil scuzzballs who delight in vandalism, creating anarchy and striking terror in the hearts of the innocent more than they do in robbing.

Michael Winner lays everything on with characteristic heavy-handedness. Early on in the piece, Charles Bronson states: “My heart bleeds for the underprivileged, yeah” while redneck co-worker William Redfield retorts “The underprivileged are beating our brains out. Stick ’em in concentration camps, that’s what I say.” The initial assault that we see – of hoods breaking in, murdering Bronson’s wife and raping his daughter (even spray-painting her ass with a red target) – has been designed to strike a mortal spike into the heart of Charles Bronson’s traditional identity as a family man. Later Bronson asks son-in-law Steven Keats: “What are we? What do you call people who are faced with a condition of fear and do nothing about, just run and hide,” to which Keats can only timidly reply “Civilised?”

It is not long before Bronson is given to realise: “What about the good old custom of self-defence? If the police don’t defend us, maybe we ought to do it ourselves.” What is seen as the ideal response to such urban anarchy is the legally permissible carrying of guns in the state of Arizona. Bronson travels to visit Stuart Margolin’s developer in Tucson where Margolin is given to speeches like: “You’re probably one of the knee-jerk liberals who thinks we gun boys just shoot our guns because it’s an extension of our penises” or “Unlike your city, we can walk through our parks and streets at night and feel safe. Muggers out here just plain get their asses blown off.” (Death Wish could almost be a 93-minute NRA recruiting commercial as the arguments are the same ones used by the NRA to justify gun ownership). Winner makes frequent contrast between the urban jungle of New York City, which is seen as a nightmare place to live, and Arizona, which is seen as an almost utopian place because of the lack of urban anxieties afforded by liberal gun laws – there is even talk about how the people of Arizona enjoy the wide-open freedom derived from the lack of urban overcrowding and the strong implication given that this is what gives rise to crime. We also see Charles Bronson getting ideas from watching a mock Western town simulation, during which Michael Winner seems to be drawing a connection to Western frontier justice.

Charles Bronson has a character arc not dissimilar to Dustin Hoffman’s character in Straw Dogs (1971), which sets up a man with token liberal views whose journey is to recognise the need to take up arms against the rampant injustice around him. To this extent, Bronson is even characterised as a man who was a conscientious objector during the Korean War (something that becomes hard to swallow given Bronson’s subsequent career as an action star in vigilante-type roles). The film even indulges in a fantasy of vigilantism where it is seen that Bronson’s crime spree causes the citizenry of New York everywhere to fight back against muggers – that the solution to rampant urban crime is simply for people to stand up and no longer fear the cowards who prey on them. (For an overview of the genre see Vigilante Films).

In all of this – whether reacting to the shock of his wife being murdered or trying to show euphoria at having killed a mugger – Charles Bronson’s face never varies from a brick-like stoicism and a squinting mien. It is a (lack of) performance that Bronson managed to make an entire career out of. There would hardly be any part of Death Wish (or indeed any of his other films) where one can say they ever remember Bronson smiling. One of the more amusing scenes is watching a tall, gangly young Jeff Goldblum (in his first ever screen role) playing one of the muggers that attack Hope Lange and Kathleen Tolan while screaming “Rich cunts. I hate rich cunts.” Later-to-be director Christopher Guest also turns up as a cop near the end.

The sequels were:– Death Wish II (1981), Death Wish 3 (1985), Death Wish 4: The Crackdown (1987) and Death Wish V: The Face of Death (1994). All starred Charles Bronson. Michael Winner returned to direct the first two sequels. Death Wish (2018) was a remake from Eli Roth starring Bruce Willis. Also of note is Death Sentence (2007), which is based on the book sequel to Death Wish, although this completely changes the names of the characters and the plot.

Trailer here