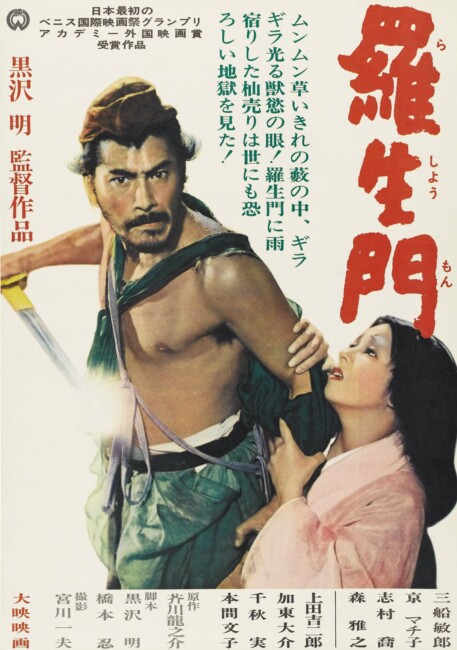

Japan. 1950.

Crew

Director – Akira Kurosawa, Screenplay – Akira Kurosawa & Shinobu Hashimoto, Based on the Short Stories Rashomon and In a Grove by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Producer – Jingo Minoru, Photography (b&w) – Kazuo Miyagawa, Music – Fumio Hayasaka, Production Design – So Matsuyama. Production Company – Daiei.

Cast

Toshiro Mifune (Tajomaru), Machiko Kyo (Takehiro), Masayuki Mori (Masako), Takashi Shimura (Woodcutter)

Plot

In 12th Century Japan, three men shelter from the rain at the Rashomon gate and discuss a murder trial that came before the local magistrate’s court. The court convened to determine the truth in a case where a woman had been raped and her husband killed. Four key witnesses – the wife, a bandit and a woodsman who witnessed what happened – were brought forward to testify, as well as the dead man speaking via a medium. However, each witness had an entirely different interpretation of the events. The bandit claimed he was overcome with lust for the woman when he saw her passing through the woods and how she insisted that he and the husband fight a duel for her. The wife instead tells how she stabbed the husband because he would not forgive her after the bandit forced himself on her. The husband tells how he could not stand the shame of what happened and committed suicide. The woodcutter, who secretly observed, tells a fourth different story in which nobody acted with honour.

Akira Kurosawa (1910-98) was one of the great directors of the 20th Century. Although he had made eleven films before this, Rashomon was Akira Kurosawa’s first film to be released in the West. It immediately propelled Kurosawa to international acclaim, with the film winning a special honorary Academy Award in 1952. Akira Kurosawa would go on to make a number of incredible works during the 1950s with his samurai epics The Seven Samurai (1954) and Yojimbo (1961), which have both been endlessly imitated by Western filmmakers. Later, Kurosawa graduated to epic productions of Japanese historical spectacle with the likes of Throne of Blood (1957), Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985), among others.

What was striking about Rashomon at the time was its denial of the objectivity of experience that film offers. Film up to that point, with occasional exceptions, had been regarded as a literal depictive experience. What the camera showed was, according to the suspension of disbelief we accorded the filmmakers, a “true” experience where the camera was merely observing what was happening. Akira Kurosawa changed that.

Rashomon provides the basic set-up of a murder mystery – a murder and a rape have happened, a crime has clearly been committed and a court is convened to determine the truth. However, after providing these brief anchor points, Akira Kurosawa proceeds to do everything else except show what happened. Four accounts of what happened are offered, including one from the murdered man’s ghost as relayed through a medium. Each account differs wildly – uniquely each of the principals insists that they were the one who conducted the murder. In the end, no resolution is found and the four stories are left irreconcilably disunited.

What Akira Kurosawa appears to saying is that our perception, or at least the way we re-present the truth to others, is something that is marred by our own pride. Each of the principals seems to have their own self-justifying reasons for telling their version of the story – even though they claim guilt in the incident, their version of the story is the one where they come out the most honourably. The version that we could presume to be the least biased, the woodcutter who was merely observing, is notable in that it shows that nobody acted honourably – in his account, the stylishly directed duel that the bandit says he and the husband fought is shown to only be clumsy stumbling.

Rashomon is striking in its implication that it is not possible to ever find objective truth. Ultimately, maybe this was too pessimistic an idea for Akira Kurosawa to handle and this is why he inserts a maudlin framing device. Here, just as the story is finished being told, a baby starts crying in the shelter. While one man expresses no concern, both the priest and woodcutter offer to take it in. The film leaves us with the sense that the weight of finding existential truth can be overcome by good deeds – ie. the Japanese focus of acting responsibly as a community.

Rashomon is a film that was very much of its time and culture. Being Japanese, a society that is rigidly patriarchal and insanely honour-bound, the issue when the women is raped is not so much concerned with any sense of shock and outrage at her violation when it comes to her interpretation of the story but the sense of shame she feels before her husband at having allowed this to happen.

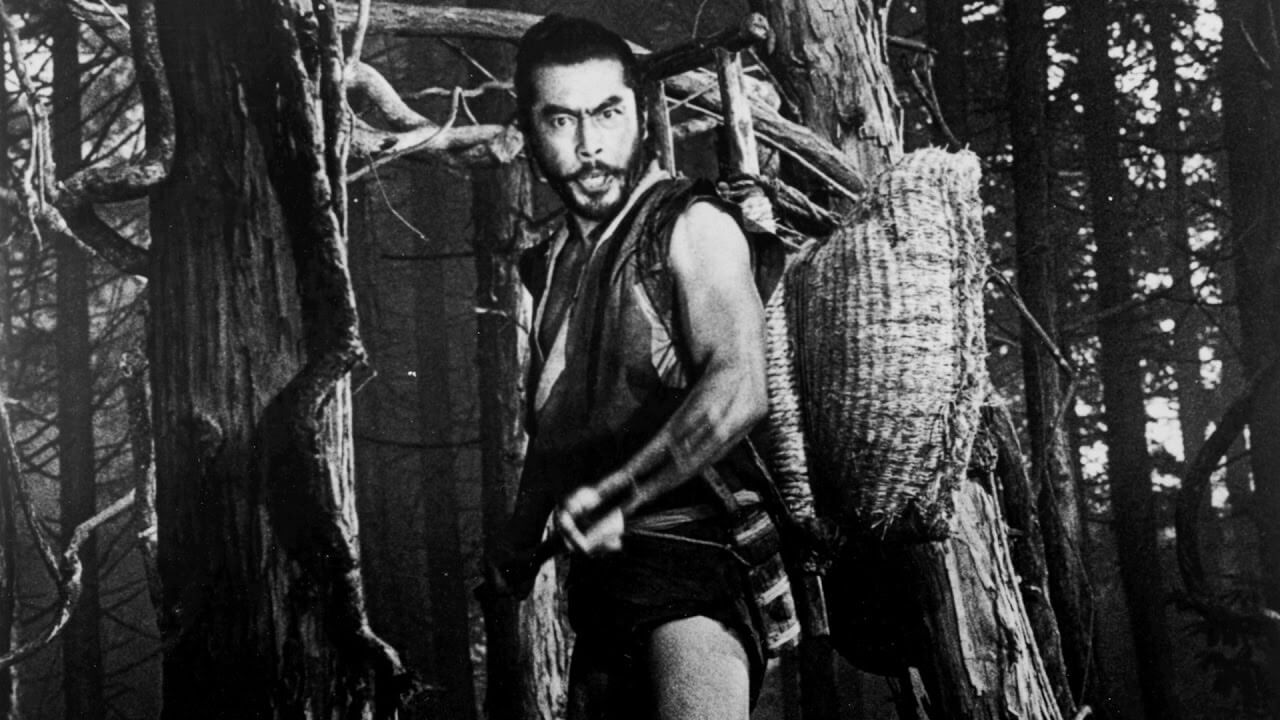

Akira Kurosawa’s visual style is at a point of near perfection. The film’s ritually stylised beauty and violence is haunting. Images have a profound beauty – from the masterful and balletic swordplay to the broken structure of the ‘devil’s gate’ effervescent in the rain or the image of the wife trailing her long veil, sitting in the forest beside her white horse. There are striking and subtle touches that emphasize the subjectivity of the story – how the wife has her face painted differently for each interpretation, or how the courtroom is set up so that viewer literally becomes the never-seen judges.

Rashomon also brought to attention Toshiro Mifune who became a much-respected international actor. Mifune certainly gives a wildly over-the-top performance here, baying like a madman. The best performance comes from the unrecognised Machiko Kyo as the violated wife who makes an extraordinary number of character changes – from blushing innocent to calculating temptress – for each different account of the story.

Like many of Akira Kurosawa’s films of the era, Rashomon was enormously influential and influenced a number of Western films. It was remade in a Western setting as The Outrage (1964) and by the Japanese as the little seen Misty (1996). Other films have borrowed its subjective multiple point-of-view storytelling format including the likes of Iron Maze (1991), The Usual Suspects (1995), A Clean Kill/Her Married Lover (1999), Courage Under Fire (1999), Go (1999), The Hole (2001), One Night at McCool’s (2001), Basic (2003), Hero (2002), Wonderland (2003), Hoodwinked! (2005), Vantage Point (2008) and Cover Versions (2018), even episodes of tv series such as Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94) and Thirtysomething (1987-91). It was also a film that was enormously influential on the French New Wave and films such as Last Year in Marienbad (1961), Michaelangelo Antonioni’s Blow Up (1966), Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf (1968) and Peter Weir’s The Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), films whose essential truth concerning a narrative puzzle is ultimately withheld from us.

Akira Kurosawa became perhaps the greatest of all Japanese directors over the next forty years with his aforementioned samurai films and historical epics. His samurai films have inspired numerous imitators and been transplanted into science-fiction settings in the likes of Battle Beyond the Stars (1980) and Omega Doom (1996), while his comedy The Hidden Fortress (1958) is purported to have inspired George Lucas in Star Wars (1977). The only other fantastic film Akira Kurosawa ever made himself was the stunningly beautiful anthology of ghost stories Dreams (1990).

Trailer here