aka Dark Prince

Crew

Director – Gwyneth Gibby, Screenplay – Craig J. Nevius, Producer – Anatoly Fradis, Photography – Yevgeny Guslinsky, Music – Deborah Millison, Music Supervisor – Paul di Franco, Visual Effects – Stewart Motion Picture Services (Supervisor – Jim Stewart), Production Design – Konstantin Forostenko. Production Company – New Horizons/Afra/Mosfilm/Transpacific Corp.

Cast

Nick Mancuso (Marquis de Sade), Janet Gunn (Justine), John Rhys-Davies (Inspector Marais), Charlotte Nielsen (Juliette), Irina Malysheva (Madame de Montreuil), Irina Nizina (Renee de Montreuil), Alexander Belyavsky (Judge de Bory), Alexander Rezalin (Latour), Mikhail Shevchuk (Gaufridy)

Plot

The writer and notorious libertine The Marquis de Sade is sentenced to The Bastille by a Parisian court for the murder of a girl, which happened just as de Sade described in one of his books. Justine tries to get to see de Sade but is refused by the police and the courts. However, she bribes the guards and is taken to see him. She is at first taken aback by de Sade’s unrestrained wolvishness. She begs from him knowledge of her sister Juliette who wrote of knowing de Sade before she went missing. Instead de Sade holds off telling and asks her to bring quills and paper whereupon he starts dictating chapters of a book to her. He tells her his story, of how he had to marry Renee de Montreuil to escape bankruptcy only to find that her mother controlled all the finances. Under his wife’s nose and then in front of her, de Sade let a life of wickedness, consorting with prostitutes. He then dictates the chapters that describe how Juliette came to Paris as an actress and he took her under his tutelage and determined to corrupt her. Through listening to this, Justine comes to realize that she is attracted to de Sade and moreover that he did not kill Juliette but that Juliette has been captured and used as a sadistic plaything by others.

The life story of the Marquis de Sade (the man who lent his name to the term ‘sadism’) has always proven a fertile one for filmmakers, even if most of the films never come anywhere near an accurate portrait of the man. Films based on the Marquis de Sade story so far have included parts of The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade (1966); De Sade (1969) with Keir Dullea; the hilariously obscene Marquis (1989), which re-enacted de Sade’s story with talking animals; the Italian exploitation film Marquis de Sade (1994); Quills (2000) starring Geoffrey Rush; and the French Sade (2000). Not to mention De Sade’s frequent incarnation in various horror films and oddities – from Night Terrors (1993) with Robert Englund as his modern-day descendant and The Skull (1965) where his activities proved so evil that his skull remains possessed in the present day; to X Marquis the Spot (2000), an episode of Jack of All Trades where de Sade was running a BDSM brothel in the South Seas; even an episode of Fantasy Island (1978-84).

This version of the story was a Russian-shot production co-produced by Roger Corman’s New Horizons company. (This incidentally makes Marquis de Sade the second venture into the de Sade biopic by Roger Corman, who was also involved in the 1969 De Sade in an uncredited capacity). Director Gwyneth Gibby previously worked for New Horizons as an editor and made her debut as a director here. Following Marquis de Sade, Gibby has made a handful of other productions for New Horizons, most being genre films, with the likes of Eruption (1997), The Phantom Eye (mini-series, 1999), Nightfall (2000) and Black Scorpion Returns (2001).

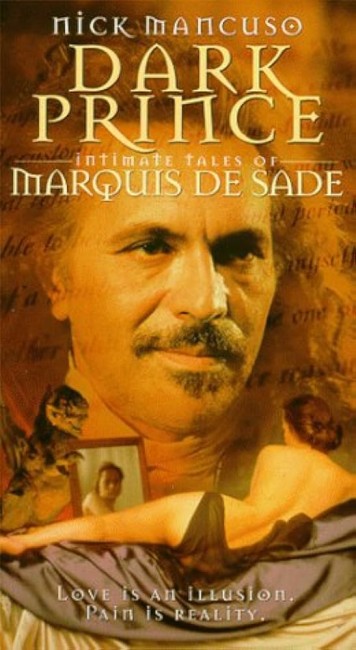

Roger Corman and New Horizons are more known for their prolific output of B-budget films than they are of historical epics. Marquis de Sade certainly starts well with the credits vying between a series of classical nude paintings and cuts to live-action footage of various models enacting the same poses. Unfortunately, Roger Corman’s usual low-budget filmmaking quickly triumphs over any more artistically minded intent upon Gwyneth Gibby’s part. The production did travel to Russia to shoot but 18th Century Paris and the sets are still conducted on a cramped budget. The role of de Sade is also miscast with Nick Mancuso, who takes the opportunity to act his head off with a wild-eyed and campy performance. (One amusing aspect is the art for the video cover, which one would swear tries to turn Nick Mancuso into a likeness of Gerard Depardieu).

On the plus side, this version tends to offer a reasonably realistic portrait of the Marquis de Sade’s character. Other film versions have been surprisingly sympathetic to de Sade – De Sade painted him as a man gone a little astray, while both Marquis and Quills showed him as a misunderstood writer. This film by contrast shows a de Sade that at least approaches the character of historical portrait – a hedonist who seemed to lack any impulse control and delighted in carnality and shocking conventional morality.

Gwyneth Gibby does a fine job of portraying the debauchery of de Sade’s marriage. Like the image of Nick Mancuso kissing bride Irina Nizina with a wanton lasciviousness during the marriage ceremony. Or his languishing with whores while sitting in front of his bride and her mother. “You’re humiliating your wife,” his mother-in-law complains, to which Mancuso responds with an airily dismissive “She’ll get used to it.” Regular Corman writer Craig J. Nevius’s script takes the view that de Sade’s principal turn-on was cruelty and humiliation and even writes a startling sequence where de Sade orders his servants to rape his wife.

Alas the rest of the film’s portrait of the Marquis de Sade is often wildly inaccurate. The film has his novel 120 Days of Sodom published and cited as one of the works that led to his sentencing to The Bastille, whereas historically de Sade only wrote 120 Days of Sodom when he was imprisoned and never completed it, while the manuscript was stolen during the sacking of The Bastille, fell into the hands of a private collector and was not published until 1904, well over a century after de Sade’s death. The aspect about the character of Justine coming to de Sade in jail and taking dictation is a fiction – as Quills accurately depicted, de Sade had the maid Madeline le Clerc smuggle his manuscripts out to a publisher.

Most of all, the part about de Sade being framed for a murder is an entire fiction – de Sade was much more mundanely convicted for sodomy and the use of a non-lethal aphrodisiac in his first two arrests and upon the last occasion for his writings lampooning Napoleon. Furthermore, he had been moved out of The Bastille prior to its storming during the French Revolution – although the film does amusingly suggest that the French Revolution was caused by a woman who was enamoured by de Sade and trying to stop him from being guillotined.

There is absolutely no historical basis for this film’s story about de Sade being convicted of a murder that he supposedly described in one of his books, nor any basis about claiming that he escaped from The Bastille to freedom (he was in actuality released the following year in an amnesty on prisoners in the aftermath of The Revolution, although was reimprisoned several years later). It is true that de Sade wrote two books Justine (1791) and Juliette (1797-1801), although the characters described therein bear little resemblance to the two counterparts here. Neither of these books describes Juliette being murdered as the film claims. Furthermore, both of these books were published after the Marquis de Sade was released from The Bastille so could hardly have been the cause of his being imprisoned there in the first place.

The most disappointing part of the film is its second half, which moves from an interesting depiction of de Sade’s debaucheries to incongruously become a mystery about finding the abducted sister. The end of the film improbably reveals that the missing Juliette has been abducted by a conspiracy of the respectable establishment figures that we encounter throughout. The script even more ludicrously then has de Sade arrive to expose them and save Juliette from their cruelties. The problem the film has is that, in having established de Sade as a debauched and vile figure throughout, it then unconvincingly turns him around to become the hero of the day and moreover a character that has the moral high ground over the people torturing Juliette. The film seems to want us to draw a distinction between de Sade’s debaucheries, sadistic cruelties and humiliations, which it asks us to see as being innocent, and the establishment figures’ debaucheries, sadistic cruelties and humiliations, which it asks us to see as being nasty and irredeemable because they hide behind a mask of social hypocrisy. It is a case of having your moral cake and trying to eat it too, one cannot help but feel.