UK. 1971.

Crew

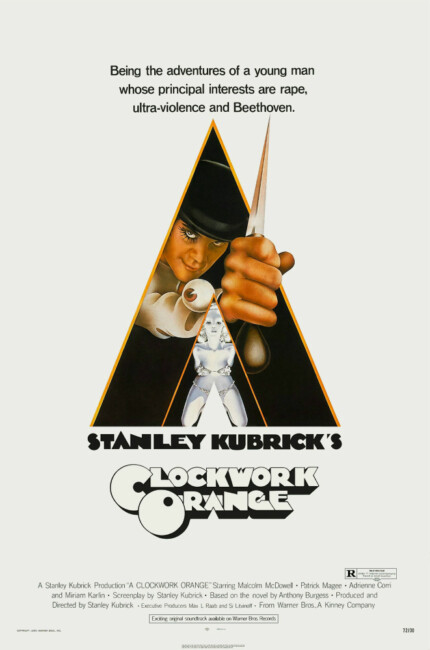

Director/Screenplay/Producer – Stanley Kubrick, Based on the Novel by Anthony Burgess, Photography – John Alcott, Music – Walter Carlos, Production Design – John Barry, Erotic Sculptures – Herman Makkink. Production Company – Polaris Films/Warner Brothers.

Cast

Malcolm McDowell (Alex DeLarge), Patrick Magee (Frank Alexander), Warren Clarke (Dim), James Marks (Georgie), Michael Bates (Chief Guard), Godfrey Quigley (Chaplain), Anthony Sharp (The Minister), Philip Stone (Mr DeLarge), Sheila Raynor (Mrs DeLarge), Carl Dwering (Dr Brodsky), Madge Ryan (Dr Branom), Aubrey Morris (P.R. Deltoid)

Plot

England in the near future. Alex DeLarge and his gang of droogs wander the streets, indulging in acts of rape and ultra-violence. Alex is then arrested and sentenced to fourteen years for a murder. In prison, he signs up for The Ludovico Treatment, a psychological conditioning process that curbs violent tendencies, and is released cured. However, he is unable to defend himself and now finds the world a harsh and violent place. One of his former victims Frank Alexander finds Alex, offers him shelter at his house and then determines to drive Alex to kill himself in revenge for the murder of his wife. A public outcry is raised, so Alex is de-conditioned and let loose to be a thug once again.

A Clockwork Orange caused a storm of controversy when it was released. It came from Stanley Kubrick, who was in the process of emerging as one of the most original and talented directors in the world. Kubrick was certainly not new to controversy – his adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1962) brought down howls of outrage with its story of an old man seducing an underage girl, and then of course there was Dr Strangelove; or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), which dared to turn the nuclear holocaust into a giant black joke.

Stanley Kubrick maybe had the most dark and sardonic view of humanity of any director ever. Dr Strangelove, where the end of the world is treated as a giant theatre of the absurd, is one of the most blackly funny films ever made. In Full Metal Jacket (1987), the Vietnam War receives the same gallows humour treatment. Even 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) has its wondrously transcendent visions of spaceflight undercut by a bleak vision of humanity being swallowed up by its technology.

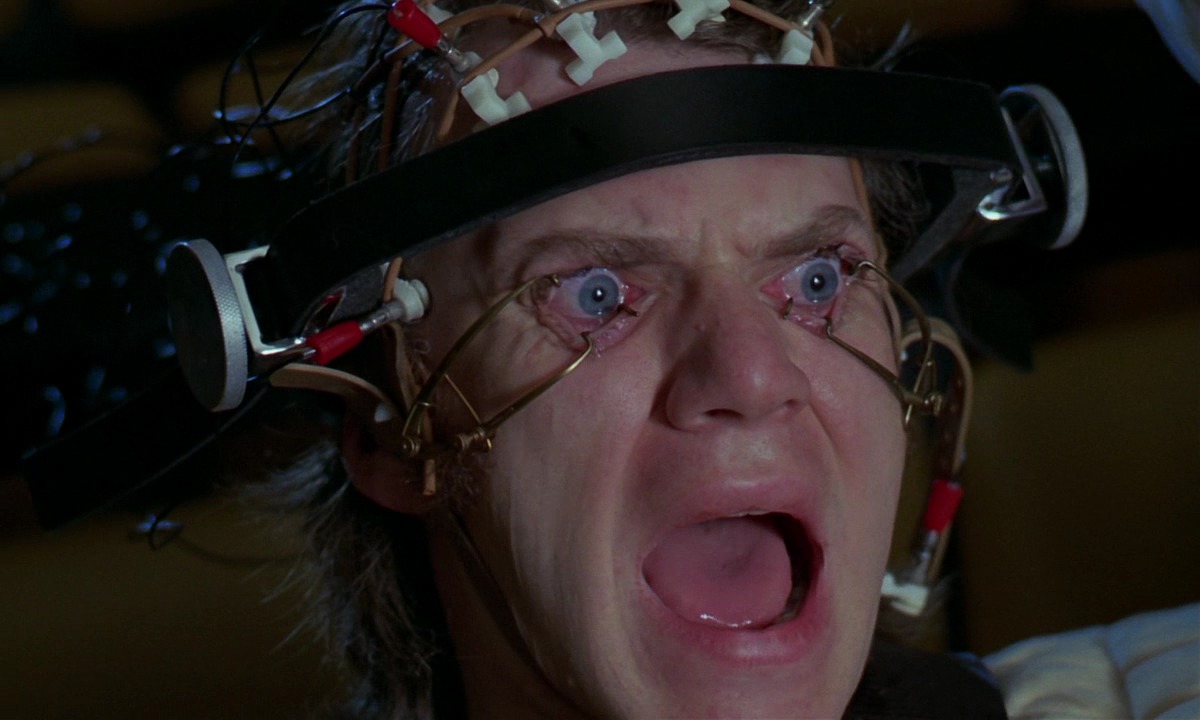

All manner of sardonic humour likewise runs throughout A Clockwork Orange. Kubrick directs the film as strident farce. The entire cast deliver their performances at the top of their voices, something that only makes the violence seem nastier. Kubrick jabs at every target he can. “Don’t touch that, it’s a priceless work of art,” says a woman of her sculpture of a giant schlong, shortly before she is battered to death by it; while in prison the Bible becomes a handy source of violent imaginings for the deprived Malcolm McDowell. The psychiatric profession are in for it too – there is that unnervingly black moment when Malcolm McDowell genuinely screams that he is cured but the doctors carry on insistent that it be continued for his own good.

What upset everybody at the time the film came out was Stanley Kubrick’s choreography of art and violence. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick choreographed spaceflight to classical music with extraordinarily poetic results. The first half of A Clockwork Orange does similar things but instead Kubrick choreographs violence with outrageously dazzling artistry – such as showing a gang fight to the strains of Rossini’s Thieving Magpie (1817). There is also the extremely nasty scene where the droogs conduct a beating and rape during which Malcolm McDowell kicks a victim in the head while singing Singing in the Rain.

A Clockwork Orange is nothing less than a giant black joke on its audience upon Stanley Kubrick’s part. Kubrick spends half of the film leaving us shocked and horrified at the protagonist and his actions. But then halfway through, Kubrick turns Malcolm McDowell into a figure of sympathy. At first, we do not even notice this. However, as the prison and brainwashing scenes continue, McDowell becomes entirely heartbreaking in the injustices rained upon him. Of course the ending we arrive at – where the conditioning is undone and Malcolm McDowell is released and heads out into the world with the camera closing in on him already dreaming of more ultra-violence he can now unleash again – is totally outrageous. By this point, Stanley Kubrick has manoeuvered the entire film around to turn Malcolm McDowell into a sympathetic victim. Indeed, Kubrick has been so successful at manipulating audience sympathies that we are cheering McDowell on and celebrating his being allowed to go free and cause more mayhem. This is the genius of Stanley Kubrick’s grand black joke.

A Clockwork Orange is adapted from a 1962 novel by Anthony Burgess. In the book, Burgess conducted a unique experiment in creating a future street argot – which he called Nasdat, importing words from Russian slang – some of which survives in the film, albeit less densely than in the book. Anthony Burgess was raised a Roman Catholic and originally wrote A Clockwork Orange as a parable about Christian free will and forgiveness, saying that for a Christian to forgive he must also forgive the most horrifying acts. (The book was based on an incident during WWII where Burgess’s wife was assaulted by soldiers and ended up miscarrying). However, the film is as much a black joke on Burgess than anything else. The moral of the story certainly tends to get lost in the film version and most certainly in the ending where Stanley Kubrick upstages and changes Burgess’s ending, which had Alex eventually seeing the error of his ways and growing up.

Despite the controversy surrounding it, A Clockwork Orange was nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards, the BAFTAs and the Golden Globes. Shortly after the film came out, there was media hysteria in England over hooligan attacks that people claimed were inspired by the film. After being personally pilloried in the press for inciting violence and receiving death threats, Stanley Kubrick withdrew A Clockwork Orange from circulation and refused to release it in England until after his death (which occurred in 1999). He also refused a video release, so for a number of years the film developed a flourishing cult through arthouse and midnight screenings of the theatrical print. The film was eventually released to video in 2000.

The making of A Clockwork Orange is covered in the documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures (2001). It was spoofed in Tenacious D in the Pick of Destiny (2006) while the Droogs later make cameo appearances in Space Jam: A New Legacy (2021).

Other Stanley Kubrick films of genre interest are the aforementioned nuclear war black comedy Dr Strangelove; or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the Stephen King haunted hotel adaptation The Shining (1980) and Steven Spielberg’s posthumously completed A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) (2001) about an android boy.

Trailer here