Crew

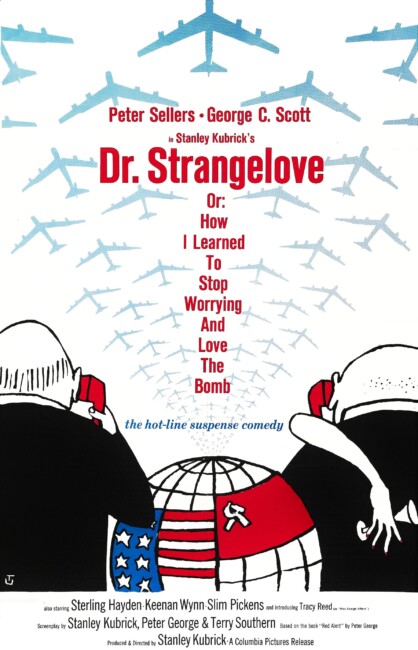

Director/Producer – Stanley Kubrick, Screenplay – Stanley Kubrick, Peter George & Terry Southern, Based on the Novel Red Alert by Peter George, Photography (b&w) – Gil Taylor, Music – Laurie Johnson, Special Effects – Les Bowie & Wally Veevers, Makeup – Stuart Freeborn, Production Design – Ken Adam. Production Company – Hawk Films.

Cast

Peter Sellers (Captain Lionel Mandrake/President Merkin Muffley/Dr Strangelove), George C. Scott (General Buck Turgidson), Sterling Hayden (General Jack D. Ripper), Keenan Wynn (Colonel Bat Guano), Slim Pickens (Major T.J. ‘King’ Kong), Peter Bull (Ambassador de Sadesky)

Plot

Convinced that there is a Communist plot to sap America’s precious bodily fluids via fluoridation, General Jack D. Ripper sends a wing of B-52 bombers armed with nuclear warheads to bomb Russia. Captain Lionel Mandrake tries to persuade General Ripper to hand over the recall codes but Ripper commits suicide before he can do so. President Merkin Muffley contacts the Russians to try and stop the bombers. All but one of the bombers is successfully destroyed but this, under the command of Major ‘King’ Kong, gets through to drop its payload. The Russians retaliate by detonating their Doomsday Weapon, a bomb that will leave the world encircled by radiation for the next hundred years. The President and military head for the mineshafts to hide but worry about the possibility of Communist infiltration there.

At the time that he made Dr Strangelove or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Stanley Kubrick was just beginning to blossom as the celebrated auteur he is regarded as today. He had made a thriller The Killing (1956), the acclaimed anti-War film Paths of Glory (1957), had taken over as director of the gladiator epic Spartacus (1960) at the last moment, and then courted controversy with his adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1962). If Stanley Kubrick was relatively unknown then, Dr Strangelove or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb made everybody take notice of his name. Subsequently, of course, Kubrick would go onto make greats like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1974), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

At the time that Dr Strangelove or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb was made, The Cold War had suddenly intensified from the veiled spectre of nuclear holocaust that seems to hang over the 1950s into the stark sweaty tension of the immediately now. The Cuban Missile Crisis suddenly made the threat of nuclear war into an imminently real possibility. Consummate with this intensification, nuclear holocaust themes in cinema moved from the disguised allegories of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), Them! (1954) and Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1954) to harshly realistic portraits, beginning with On the Beach (1959). The same year as Dr Strangelove also saw the bared-to-the-edge Fail-Safe (1964), which had many similarities to this, and not long after the controversial British pseudo-documentary The War Game (1965).

Dr Strangelove is the one among these nuclear war films that has gone onto become a classic and is one that frequently turns up on some critics’ All-Time Top Ten lists. Originally, Dr Strangelove was not even intended as a comedy. Stanley Kubrick had purchased the rights to Peter George’s novel Red Alert (1958). The novel is a straight tale of a nuclear accident but the more he began to work on the script the more Kubrick came to the realization that the subject matter was so grim that the only way he could treat it was as an out-and-out black comedy. And so he hired comedy writer Terry Southern, best known for Candy (1968), to come in and rework the material.

A dark cynicism about the human condition underpins Stanley Kubrick’s work and Dr Strangelove was the first occasion when that hysterical blackness emerged into the open. There are few directors whose work ever inhabited places as far away from the feelgood rosy sentiment and morally upbeat world of the American mainstream. Kubrick construed films as giant black jokes – 2001: A Space Odyssey charts an epic vision of human evolution, yet for all that, the people in the film are blank and stripped of humanity and have become eclipsed by their technology; A Clockwork Orange is a grand joke on its audience wherein Kubrick first outrages us with his artfully choreographed scenes of violence and then wheels our sympathies around until we celebrate Malcolm McDowell’s being freed to commit more mayhem; or the merciless unblinking cruelty of Kubrick’s depiction of a military boot camp in Full Metal Jacket. Perhaps what sets Dr Strangelove above the other abovementioned nuclear holocaust films is not merely the fact that it depicts the end of the world but Stanley Kubrick’s willingness to go out on a limb and turn the unthinkable into a grotesque black joke.

Kubrick shoots the background of the film with documentary-like detail, overwhelming us with a dense bombardment of codes and military procedures. There is the alarming sense that what is happening is the real thing. At the same time, Kubrick contrasts this with characters that are buffoons and have cartoon names. It has a grotesquely funny effect.

Part of what makes the humour so black in Stanley Kubrick’s films is the coolly detached remove he places his camera at. He has the amazing ability to keep his camera at a static distance and unleash outrage and black hysteria in front of it, observing yet remaining wholly aloof from what is happening. Sometimes this would overbalance into farcical cruelty, as in Jack Nicholson’s performance in The Shining. Here it is unnervingly on target, never more evident than the intense sense of squirming discomfort that Kubrick conjures during the midst of the war conference where George C. Scott receives a personal call from his secretary and tries to keep details hushed while seated around a giant circular conference table.

Kubrick sets up scenes that get black and blacker. An Air Force base in invaded by soldiers with shootouts occurring in front of billboards announcing that ‘Peace is Our Profession’. The opening credits play against the absurd imagery of a bomber refueling in mid-air, where a long pipe dropped between planes and the bumping rhythm is deliberately choreographed like an act of sexual intercourse. There is an hysterical scene with Peter Seller’s Air Force Captain having finally found the recall codes and trying to call through with them, only to find he is unable to make a collect call and then having to request Keenan Wynn shoot up a Coke machine to get the change to make the call – “You’re going to have to answer to the Coke Company for this,” the stony-faced Wynn retorts. The film ends on stock footage of a mushroom cloud as the world is destroyed to the blacker-than-black accompaniment of the Vera Lynn WWII hit song We’ll Meet Again (1939).

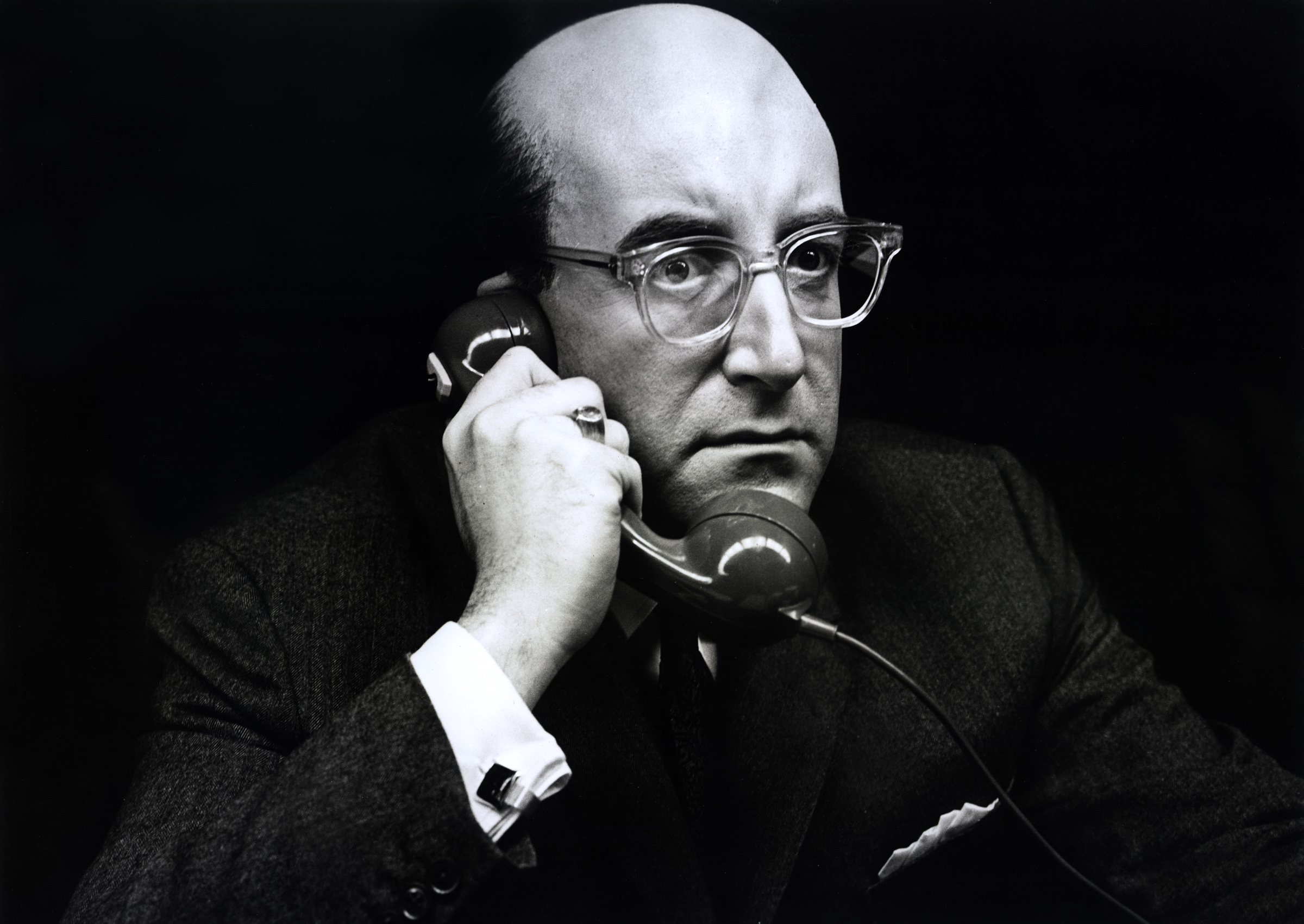

The triumph of the film belongs as much to the actors as it does Stanley Kubrick. Peter Sellers was at the height of his popularity and takes on another of the multiple roles he specialised in. His fruity pip-pip tally-ho Captain Mandrake is the least effective but he is particularly memorable as the wheelchair-ridden Dr Strangelove with a mechanical arm that is constantly taking on a jerky life of its own, trying either to form a Nazi salute or strangle him. Sellers is positively hilarious as the wimpy President Mirkin Muffley, revealing some remarkable improvisational talents in the scenes on the phone to the Russian Premier – “Do you happen to have the number of the Air Base on you? Don’t tell me I’m not, I’m just as capable as being sorry as you. I’m more sorry than you.”

There is wonderful support from everybody else. George C. Scott gives what must vie with Patton (1970) to be his best performance. In fact, his gung ho boyish God-fearing, Stars-and-Striper general is the most likable character in the film. [You can make direct contrast to Fail-Safe where the character espousing identical points of view, played by Walter Matthau, was seen as the most vile and inhumane in the film, whereas here Scott is the most normal of them all].

Dr Strangelove was nominated at the Academy Awards that year for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Peter Sellers) and Best Adapted Screenplay.

The making of Dr Strangelove was also depicted in the Peter Sellers biopic The Life and Death of Peter Sellers (2004). It was also spoofed in The Congress (2013).

Stanley Kubrick’s later ventures into genre territory were 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), The Shining (1980) and Steven Spielberg’s posthumously completed A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) (2001).

Trailer here