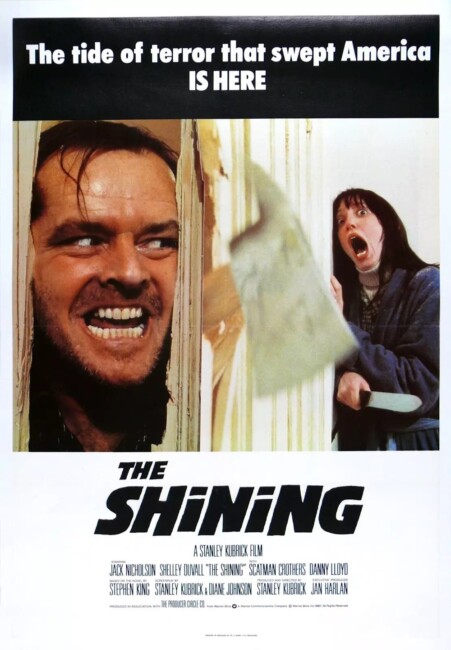

USA/UK. 1980.

Crew

Director/Producer – Stanley Kubrick, Screenplay – Stanley Kubrick & Diane Johnson, Based on the Novel by Stephen King, Photography – John Alcott, Music – Wendy Carlos, from Bela Bartok, Rachel Elkind, Gyorgy Ligeti & Kryzsztof Pendericki, Makeup – Barbara Daly & Tom Smith, Production Design – Roy Walker. Production Company – Hawk Films/Peregrine/The Producer Circle Company/Warner Brothers.

Cast

Jack Nicholson (Jack Torrance), Shelley Duvall (Wendy Torrance), Danny Lloyd (Danny Torrance), Scatman Crothers (Dick Halloran), Philip Stone (Delbert Grady), Joe Turkel (Lloyd)

Plot

Writer Jack Torrance takes a job as winter caretaker of the Overlook Hotel in the remote Colorado mountains. He moves in, along with his wife Wendy and son Danny, in the hope that the isolation will cure his writer’s block. However, as the weather isolates them, Jack descends into madness. Apparitions from the hotel’s past then appear, imploring Jack to kill his family.

At the time he made The Shining, Stanley Kubrick had grown a reputation as one of the most daring and extraordinary directors of his generation. He had constantly courted outrage and the limits of good taste with works like Lolita (1962) about paedophilia; Dr Strangelove or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), which turned nuclear war and the end of the world into a grotesque black comedy; and A Clockwork Orange (1971), which shocked everybody by choreographing rape and ultra-violence to classical music and supposedly inspiring real-life hooliganism. All of Stanley Kubrick’s works had been acclaimed for their directorial virtuoso and groundbreaking technical brilliance, especially 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), which is widely considered not only one of the best sf films ever made but a landmark of cinema itself.

The Shining came just at the time when Stanley Kubrick’s reputation was mellowing from brilliant young artist into middle-age and where stories of him as an eccentric recluse and a harsh and exacting control freak were beginning to emerge. This also became the point from which his projects took increasing longer times to be mounted – between The Shining in 1980 and his death in 1999, Kubrick would only make a total of two other films, Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

.Kubrick adapted a novel from Stephen King – in fact, The Shining (1977) was only Stephen King’s third novel. King had drawn inspiration for the book in 1974 when he and his wife went to stay at the Stanley Hotel in Colorado. They checked in just as the hotel was packing up for the end of the season. King was struck by the haunted feeling of passing through a hotel filled with staff but empty of guests, experiencing bands playing to an empty dining rooms and the like.

Certainly, The Shining is one of the more divided films in Stanley Kubrick’s canon of work. It was a big hit but received mixed reviews when it came out. In either liking or hating The Shining, audiences seem divided between whether they are Stanley Kubrick fans or Stephen King fans – the Kubrick fans appreciate the master’s skill, the King fans deplore Kubrick’s dumping of substantial parts of the story and the substitution of a more enigmatic, elliptical plot where things are not always clear. Stephen King has ambiguous feelings about the film, although does denote The Shining with a special asterisk in his list of Top 100 horror films in his genre study Danse Macabre (1981).

Why Stanley Kubrick bothered to buy the rights to the book at all is a mystery. He seems to have been wanting to make something very different to the much more straightforward ghost story that Stephen King told. Many aspects of the novel remain but in partial form that does not make sense on screen. In the book, Jack is a recovering alcoholic, which the hotel comes to play upon in seducing his mind. In the film we receive no explanation of his drinking problem, which makes Jack Nicholson’s line “I’d give anything for a drink,” (which is the equivalent of someone idly wishing to sell their soul to The Devil) confusing to anyone unfamiliar with the book and cuts all the underlying character tensions in one swipe. Nor is Kubrick interested in the titular shining. In the book, the hotel wanted the shining – Danny’s natural clairvoyant gifts – and sought to add his considerable power to its own but this is not clear at all in the film. Indeed, the shining is of almost no relevance to the story. The scenes where Danny Lloyd uses a talking finger to demonstrate the shining seem incredibly silly. Kubrick has also thrown out Stephen King’s menagerie of sinister hedge animals – this was well before the CGI revolution and Kubrick believed the technical feasibility of bringing the hedge animals come to life was beyond him. In their place, he substitutes a perhaps even better sustained climax following a demented axe-wielding Jack Nicholson through a snowbound hedge maze with his Steadicam.

On screen, The Shining is no longer a story about a haunted hotel, as much as it is one about writer’s block. Of all the themes in the book, this was the one that Stanley Kubrick chose to bring out and amplify. Perhaps this is because writer’s block was clearly the issue closest to his own heart. Kubrick took years, sometimes decades, to make films – he spent 15 years on A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) (2001) and never completed it in his lifetime; it was seven years between The Shining and his next film, Full Metal Jacket, and twelve years between Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut. Kubrick was relentless in the pursuit of perfection, taking a record 160 takes of one shot with Scatman Crothers here at one point. You could maybe even draw a connection between Kubrick’s 160 takes of a single shot and the scene where Shelley Duvall finds Jack Nicholson has written hundreds and hundreds of pages saying “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”. Indeed, put a pair of glasses and a beard on Jack Nicholson in the film and he would even look a dead ringer for Stanley Kubrick.

Stanley Kubrick’s films have an underlying sense of people encountering an insanely rational world – the cool and patient but murderous logic of HAL in 2001; the Cold War war political machine strangling in its own absurities in Dr Strangelove; the cruelty of the psychologists attempting to alter behaviour in A Clockwork Orange; the authoritarianism of a military boot camp exploding into violence in Full Metal Jacket; the innocent Tom Cruise stumbling out beyond the confines of his marriage and into a conspiracy in Eyes Wide Shut. Kubrick’s fear is that the very systems we live in are being run by lunatics and madmen who mouth the most insane sentiments with calm rationalism. Kubrick’s sentiments are at their blackest in The Shining. His vision of the insanity unleashed is at its most malevolent in the scenes with a definitely out-of-control Jack Nicholson running amok with an axe and bashing down a door to call “Honey, I’m home.”

In terms of a horror film, Stanley Kubrick has made a concerted effort to take the haunted house story away from Gothic associations. The hotel and corridors are brightly lit and ultra-modern instead of Gothic and shadowy, and there are none of the usual bumps in the night or busty heroines in diaphanous nightgowns. Instead, The Shining almost entirely consists of brooding ominousness. Few films loom with such a threatening sense of bad things on the verge of erupting. There is a marvellously foreboding opening with Kubrick’s camera serenely gliding through the air over the Colorado mountains and eventually closing down in on Jack Nicholson’s tiny VW Bug, all to the menacingly stentorious thunder of Ligeti on the soundtrack. Kubrick constantly maintains a sense of unease throughout – the appearances of the mystery twin girls, the never-explained vision of an elevator unleashing a river of blood (a single image that featured prominently in the promotional trailer), the echoing emptiness of the hotel and its giant main hall, even the Steadicam shots prowling through the hallways at shin height following Danny Lloyd’s tricycle and the unsettling effect on the soundtrack of its wheels alternately rattling across wood and then the silence of carpeting. When Kubrick does eventually deliver his punches, they come with a considerable jolt. There is an unearthly scene where a beautiful naked woman gets out of the bath and comes and kisses Jack Nicholson only to turn into a hideous old hag. Another is the shock dispatch of Scatman Crothers with an axe in the chest.

Stanley Kubrick’s problem as a filmmaker was that he had a misanthrope’s view of the human condition and was indifferent to ordinary human sympathy. The crucial failing of The Shining is that it lacks a sense of normalcy. Everybody is bugged out. Jack Nicholson does the Jack Nicholson thing of acting the same wild and crazy guy he did in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) and fairly much the rest of his career. Kubrick’s mistake is to let Jack Nicholson have his head and not reign him in. Where the character of Jack Torrance should have gone from normalcy to barmy, Jack Nicholson begins bonkers in the very first scene we see him in the job interview and only gets more hammy and overblown. By the second half of the film, Nicholson’s mugging has become tedious and there is nothing left for when he starts wielding the axe. Kubrick establishes no normalcy from the outset so there is no sense of an average guy going over the edge. What The Shining needed was an ordinary actor playing the part – imagine how much scarier the film would have been if the part had started out with someone like Dustin Hoffman or Martin Sheen and then the performance had worked its way up from there to the full dementia that Nicholson unleashes. (In fact, Stephen King tried to persuade Stanley Kubrick to cast Jon Voight in the part).

The others in the cast are nothing great either – Shelley Duvall spends her time perpetually on the verge of hysterics – she is all nervousness and fear, there is nothing underneath it, while Danny Lloyd is blank and inexpressive. The warmest character is Scatman Crothers – where in the book Stephen King casts Halloran as the cavalry arriving to save the day, Kubrick instead plays a black joke on the character, having him trek all the way through the snow only to get an axe in the chest the moment he arrives.

One can certainly admire The Shining for Stanley Kubrick’s technical perfection. The photography is beautiful – there is one gorgeous shot in the barroom showing a perfectly normal foreground and the background of an empty ballroom, which suddenly becomes filled with a crowd of flappers all lit in sepia-tone. There is a breathtaking shot that flawlessly cuts from Jack Nicholson looking down on the model of the maze to the tiny figures of Shelley Duvall and Danny Lloyd walking through it as seen from above. The sets are also amazing. The giant-size hall and the interconnected rooms were built on a single soundstage and the effect gives a colossal echoing emptiness. Kubrick often enjoyed making films for the sheer technical flourish that new techniques offered him – such as shooting by candlelight in Barry Lyndon (1974) or the discovery of slit scan light effects and the construction of giant-sized rotating sets for the simulation of artificial gravity in 2001. The Shining offered Stanley Kubrick the opportunity to exploit the then just emerging Steadicam technology – the use of an ultra-light camera mounted on gimbals that does not bounce during movement thus creating steady fluid tracking shots. Kubrick employs the Steadicam with often dazzling regard during the long sinister floor-level tracking shots following Danny Lloyd riding his tricycle through the hotel and Jack Nicholson’s climactic run through the maze.

The Stephen King book was later remade as a tv mini-series The Shining (1997). This time Stephen King was directly involved on script and the result is more faithful to the book, bringing out the drinking problem, the shining and faithfully rendering the hedge animals. Director Mick Garris, who had made ham-fisted adaptations of other Stephen King scripts with the abysmal Sleepwalkers (1992), the tv mini-series version of The Stand (1994) and Riding the Bullet (2004), did okay – The Shining is probably his best work – and generates reasonable atmosphere. Stephen King later wrote a book sequel to The Shining with Doctor Sleep (2013) about a grown-up Danny and this is due a film adaptation with Doctor Sleep (2019) starring Ewan McGregor as Danny.

Scenes from the making of The Shining can be seen and the film discussed in the documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures (2001). Room 237: Being an Inquiry Into The Shining in 9 Parts (2012) is a fascinating documentary where various people offer up theories as to the hidden meanings inside the film. Steven Spielberg later elaborately recreated scenes from The Shining in Ready Player One (2018) where a key clue also hinged on Stephen King’s dissatisfaction with the final product.

Other Stephen King genre adaptations include:- Carrie (1976), Salem’s Lot (1979), Christine (1983), Cujo (1983), The Dead Zone (1983), Children of the Corn (1984), Firestarter (1984), Cat’s Eye (1985), Silver Bullet (1985), The Running Man (1987), Pet Sematary (1989), Graveyard Shift (1990), It (tv mini-series, 1990), Misery (1990), a segment of Tales from the Darkside: The Movie (1990), Sometimes They Come Back (1991), The Lawnmower Man (1992), The Dark Half (1993), Needful Things (1993), The Tommyknockers (tv mini-series, 1993), The Stand (tv mini-series, 1994), The Langoliers (tv mini-series, 1995), The Mangler (1995), Thinner (1996), The Night Flier (1997), Quicksilver Highway (1997), The Shining (tv mini-series, 1997), Trucks (1997), Apt Pupil (1998), The Green Mile (1999), The Dead Zone (tv series, 2001-2), Hearts in Atlantis (2001), Carrie (tv mini-series, 2002), Dreamcatcher (2003), Riding the Bullet (2004), ‘Salem’s Lot (tv mini-series, 2004), Secret Window (2004), Desperation (tv mini-series, 2006), Nightmares & Dreamscapes: From the Stories of Stephen King (tv mini-series, 2006), 1408 (2007), The Mist (2007), Children of the Corn (2009), Everything’s Eventual (2009), the tv series Haven (2010-5), Bag of Bones (tv mini-series, 2011), Carrie (2013), Under the Dome (tv series, 2013-5), Big Driver (2014), A Good Marriage (2014), Mercy (2014), Cell (2016), 11.22.63 (tv mini-series, 2016), The Dark Tower (2017), Gerald’s Game (2017), It (2017), The Mist (tv series, 2017), Mr. Mercedes (tv series, 2017-9), 1922 (2017), Castle Rock (tv series, 2018-9), Doctor Sleep (2019), In the Tall Grass (2019), Pet Sematary (2019), The Outsider (tv series, 2020), The Stand (tv mini-series, 2020-1), Chapelwaite (tv series, 2021), Lisey’s Story (tv mini-series, 2021), Firestarter (2022), Mr Harrigan’s Phone (2022), The Boogeyman (2023), Salem’s Lot (2024) and The Monkey (2025). Stephen King had also written a number of original screen works with Creepshow (1982), Golden Years (tv mini-series, 1991), Sleepwalkers (1992), Storm of the Century (tv mini-series, 1999), Rose Red (tv mini-series, 2002) and the tv series Kingdom Hospital (2004), as well as adapted his own works with the screenplays for Cat’s Eye, Silver Bullet, Pet Sematary, The Stand, The Shining, Desperation, Children of the Corn 2009, A Good Marriage, Cell and Lisey’s Story. King also directed one film with Maximum Overdrive (1986).

Trailer here