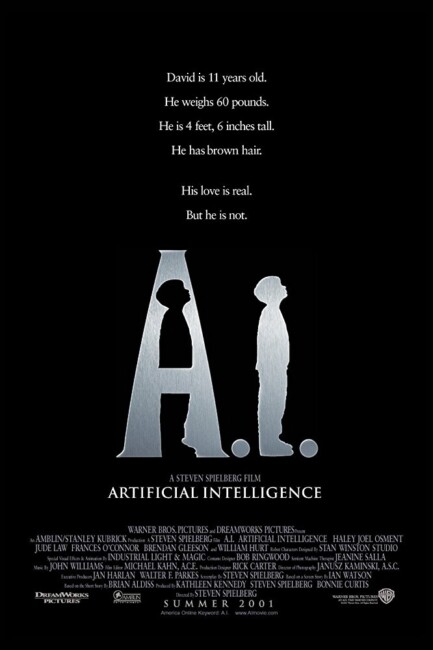

USA. 2001.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Steven Spielberg, Screen Story – Ian Watson, Based on the Short Story Supertoys Last All Summer Long by Brian Aldiss, Producers – Steven Spielberg, Bonnie Curtis & Kathleen Kennedy, Photography – Janusz Kaminski, Music – John Williams, Visual Effects Supervisors – Scott Farrer & Dennis Muren, Visual Effects/Animation – Industrial Light and Magic, Digital Effects/Animation – Pacific Data Images (Supervisor – Henry LaBouta), Special Effects Supervisor – Michael Lantieri, Robot Effects – Stan Winston Studio (Supervisor – Stan Winston), Production Design – Rick Carter. Production Company – DreamWorks SKG/Warner Brothers/Amblin./Stanley Kubrick

Cast

Haley Joel Osment (David), Jude Law (Gigolo Joe), Frances O’Connor (Monica Swinton), Sam Robards (Henry Swinton), Jake Thomas (Martin Swinton), William Hurt (Professor Hobby), Brendan Gleeson (Lord Johnson-Johnson)

Voices

Jack Angel (Teddy), Robin Williams (Dr Know)

Plot

In the future, with the melting of the polar ice caps, governments have instituted laws to curb population control. As a result, the use of androids as human companions has flourished. Professor Hobby at Cybertronics of New Jersey proposes the creation of an artificial boy that is programmed to love. Employees Henry and Monica Swinton, grieving because their son Martin has fallen into an irretrievable coma, are chosen as test subjects. Monica soon bonds with the android boy David and comes to love it. Martin then unexpectedly emerges from his coma. The mischief that Martin inspires David to causes Monica and Henry to realise that David is potentially dangerous. Unable to bear sending David back to the factory to be scrapped, Monica turns him loose in the woods. Seeking to return home to his mother’s love, the unworldwise David is captured by The Flesh Fair, a circus where robots are destroyed as entertainment. Escaping with the sex robot Gigolo Joe, David goes in search of The Blue Fairy from ‘Pinocchio’, which he believes can turn him into a ‘real boy’.

In terms of their approach to science-fiction, you could not find two directors more apart than Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg. Steven Spielberg is a director to whom filmmaking is like Peter Pan discovering Never-Never Land – a place where he can play and fly with an unspoiled sense of boyhood innocence; on the other hand, Stanley Kubrick was a cynic about humanity – he was either indifferent to people or created works like Dr Strangelove or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1963) and A Clockwork Orange (1971) that were giant black jokes where he treats audiences and characters alike as flies whose wings he was pulling off. Contrast two major works by either director – Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Both are similar films about a man who undergoes an odyssey toward a climactic meeting with the alien where he is eventually carried up and away in a wondrous light show. For Spielberg, the universe is filled with wondrous playfulness where a man merely needs to shake off the cobwebs of mundanity and discover the inner boy within; whereas for Kubrick the future is a cold oblique one where humanity has become eclipsed by its technology and needs to evolve beyond human form altogether in order to be free.

Even the approaches to filmmaking that the two took are radically opposed. Steven Spielberg is like an extrovert who has to have a finger in every pie – creating his own studio, executive producing other people’s films and numerous tv series, both live and animated; while Stanley Kubrick was a recluse and an exacting control freak who towards the end of his life spent years – in some cases literally decades – perfecting a single work. [Kubrick also holds the world record for both the longest shooting schedule on a film – 15 months for Eyes Wide Shut (1999) – and the most takes of a single scene – 160 on The Shining (1980)]. The difference is most clearly demonstrated when it comes to A.I. – Kubrick worked on the script for over fifteen years but never ended up filming it; Spielberg took two years from the point of Kubrick’s death in 1999 to script, shoot and get the finished film into theatres.

That the two should combine on a film is a major event in itself. Although, it was a collaboration where you could not help but wonder whose approach would win out. The meeting between the two appeared to be harmonious. As Spielberg recounts in the documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures (2001), Kubrick handed the script to him, saying “I believe this is closer to your sensibilities than mine.” Spielberg sought to preserve the essence of Kubrick in every detail, right down to filming under a Kubrickian veil of utmost secrecy, giving away no details of the plot up until the film’s release and even going so far as to litter deliberately misleading information in the press.

Spielberg wrote the script for A.I. himself – the first time he elected to do so since Close Encounters. He is working from an original short story Superyoys Last All Summer Long (1969) by Brian Aldiss, author of classic works of science-fiction such as Hothouse (1962), The Dark Light Years (1964), Barefoot in the Head (1969), Frankenstein Unbound (1973) and the Helliconia trilogy. Aldiss’ works have been sporadically adapted twice to the screen elsewhere with Frankenstein Unbound (1990) and the non-genre Siamese twins film Brothers of the Head (2005). Most promisingly, A.I. has a screen treatment from Ian Watson. Ian Watson is one of the most exciting and underrated science-fiction authors in the world today with books like The Jonah Kit (1975), Miracle Visitors (1978), The Book of the River and sequels, Queenmagic, Kingmagic (1988) and Meat (1988), among others, as well as some of the most cerebrally challenging short story collections imaginable. Every single Ian Watson story has a conceptual audacity – few authors play with ideas and take such daring conceptual leaps of the imagination as Watson does.

One has no idea what to expect when they sit down to watch A.I.. Even as the film unfolds, you have no idea which way it is going to turn next. The story is reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, which had several different stories happening, all of which were different in tone and only ever overlapped. Similarly, A.I. could roughly be divided into four different stories. The first half is the most customarily Spiebergian (and the only part that resembles the original short story) – the story of an android boy as he is accepted into a human family and between whom love grows. Here the film suggests what Bicentennial Man (1999) should have been but failed disastrously. (Even more so, A.I. suggests it is a grown-up version of the cult anime series Astro Boy (1963-6), which concerned an android boy built by a scientist to replace his son before being rejected and trying to find a home, where he is thrown into a circus along the way). The sequence is photographed in muted tones – in fact, this is one of the quietest films Steven Spielberg has ever made. Spielberg gently touches, although lurking in the background is an often Kubrickian coldness. One can easily imagine scenes like those where Haley Joel Osment starts laughing out of the blue at the table or the cruel games played by the brother as having been directed by Kubrick – they would have emerged with a lunging nastiness akin to the military academy scenes in Full Metal Jacket (1987).

In the very first scene, Spielberg raises the question of artificial intelligence and moral responsibility for it. Although ultimately, for all the moral weight placed on the treatment of the mechas by humans, which the film deplores, Spielberg never addresses the question of whether the emotions an android is programmed to express are real or merely simulated responses, or even the question of what real emotions are in the first place. Instead, the film heads straight for the humano-centric assumption that runs through everything from Bicentennial Man to Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94) and films like Robo-Cop (1987), Automatic (1995) and Solo (1996) – that it is merely good for an android to aspire to be human-like.

The Flesh Fair sequences are the most traditional and least interesting. They do at least feature a witty performance from Jude Law as the sex android Gigolo Joe. (This is oddly the first time that sexuality has explicitly featured in a Steven Spielberg film). Haley Joel Osment gives a fine performance, although the scene-stealer throughout much of the film is actually the character of David’s walking-talking teddy bear companion. The Flesh Fair sequences also seem to take the film in far-too-familiar places – android leaves home, must try and understand the human world, encounters anti-android prejudice from humans.

Up to about the halfway point, A.I. seems well made but unremarkable. It seems a traditional plot whose virtue is some occasionally beautifully epiphanic images that evoke a quiet “aaaah” akin to the bicycle flight across the Moon in Spielberg’s E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) – a giant glowing Moon rising over a hillside turning out to be the balloon of the android hunters; Haley Joel Osment placing his face inside a blank android face mask and Spielberg then pulling back to show his eyes looking out from a mask of his own face; a menagerie of bizarre android creations – most notably a woman android who only exists as a face with no head; and some of the effects shots like a series of bridges where vehicles run through the mouths of giant stylised heads or a flight through the drowned ruins of Manhattan where the hand of a submerged Statue of Liberty protrudes up from the water.

Towards the middle of the show, Spielberg starts to take A.I. in another direction altogether and introduces a plot about Haley Joel Osment’s quest to find the Blue Fairy from Pinocchio and become a ‘real boy’. For a time, you wonder where on Earth Spielberg can possibly take this potentially ludicrous notion – an android boy in a realist science-fiction narrative searching for a fairy from a fictional story – and wonder if Spielberg is maybe not channeling too much Disney – he did after all run When You Wish Upon a Star from the Disney Pinocchio (1940) over the end credits of Close Encounters. Instead, this leads up to a point where the story blossoms out to one extraordinary image of majestic beauty – that of David finding his Blue Fairy (amid the beautifully realised drowned ruins of Coney Island) and sitting wishing he could be a Real Boy, waiting until his batteries run down and the oceans freeze over. The poignant resonance of this image is breathtaking.

A.I. would still have been a great film if it had ended here. However, Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick have much more in store and take an extraordinary conceptual leap two thousand years into the future. It is a leap every bit as daring in its abruptness as the one between bone and spaceship that Kubrick conducted in 2001. This is the part of the film that is unquestionably Stanley Kubrick’s rather than Spielberg’s. The resonant echoes in the last part of the film and the mirror reversal of the opening sequences – where the boy created as artificial companion becomes the carrier of humanity’s last memories; the contrast between the parents at the beginning missing their son so much so that they settle for an artificial substitute to the artificial boy missing his mother so much that he settles for a simulation of her; to his becoming in effect ‘real’ and the past a simulation – are stunning in the richness of metaphor and imagery.

There is an imaginativeness to these ideas and images unlike anything found before in Steven Spielberg’s films. The finale reached where David is briefly ‘reunited’ with his mother is absolutely heart-wrenching, maybe one of the saddest moments ever in a Steven Spielberg film. It is without a doubt a moment where Kubrick’s and Spielberg’s disparate sensibilities merge with truly glorious results. Neither, one suspects, could have created such a film by themselves but together they create a minor masterpiece.

Steven Spielberg’s other genre films as director are:– Duel (1971), LA 2017 (1971), Something Evil (tv movie, 1972), Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Always (1989), Hook (1991), Jurassic Park (1993), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), Minority Report (2002), War of the Worlds (2005), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), The Adventures of Tintin (2011), The BFG (2016) and Ready Player One (2018). Spielberg has also acted as executive producer on numerous films – too many to list here. Spielberg (2017) is a documentary about Spielberg,

Stanley Kubrick’s other genre films are:– the nuclear war black comedy Dr Strangelove; or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964); 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); A Clockwork Orange (1971) about near future violence and brainwashing; and the Stephen King haunted hotel adaptation The Shining (1980). Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures (2001) is a fascinating documentary about Kubrick and his body of work.

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 2001 list. Winner for Best Director (Steven Spielberg), Nominee for Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actor (Haley Joel Osment), Best Supporting Actor (Jude Law), Best Cinematography, Best Musical Score, Best Special Effects, Best Makeup Effects and Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 2001 Awards).

Trailer here