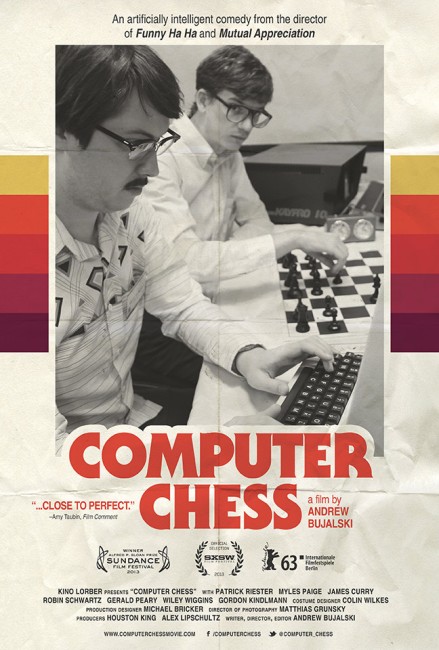

USA. 2013.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Andrew Bujalski, Producers – Houston King & Alex Lipschultz, Photography (b&w) – Matthias Grunsky, Visual Effects Supervisor – Nick Smith, Production Design – Michael Bricker.

Cast

Patrick Riester (Peter Bishton), Myles Paige (Michael Papageorge), Wiley Wiggins (Martin Buescher), Robin Schwartz (Shelly Flintic), Gordon Kindlmann (Professor Tom Schoesser), Gerald Peary (Pat Henderson), James Cabray (Leslie Cabray), Jim Lewis (John), Chris Doubek (Dave), Bob Sabiston (McVey), Cindy Williams (Pauline), Tishuan Scott (Keneiloe)

Plot

The late 1970s. Teams from several commercial and university computer laboratories around the US come together for a conference hosted by chess grandmaster Pat Henderson. Each team has designed a computer program to play chess against another team’s program in an elimination tournament. As many of them admit, the programs are getting better but there is still difficulty when it comes to grand strategy. Peter Bishton, one of the members of the team led by the renowned Professor Schoesser, finds that their program is making erratic moves that don’t seem to make sense. Trying to work out the bug in the program, he comes to believe that the computer is demonstrating a preference for playing against humans.

Computer Chess is a film from Andrew Bujalski, an American director who works within the indie scene. Bujaksi has made a handful of films with Funny Ha Ha (2002), Mutual Appreciation (2005) and Beeswax (2007), which have gained quite reasonable critical acclaim and festival attention. Bujalski is firmly associated with the so-called mumblecore movement and has shot all of his previous films on 16mm using non-professional casts. The most well-known names that Bujalski has used are here in Computer Chess – Wiley Wiggins, once the lead actor from Richard Linklater’s Slacker (1993), and film critic Gerald Peary as the chess grandmaster. A look through the film’s press kit, for instance, shows the rest of the cast lists occupations such as film editors, computer science professors and gardeners.

Computer Chess had gotten good word of mouth. I had deliberately not read too much about it (so as not to go into a film with too many preconceived ideas) thus was not expecting to review Computer Chess as a genre film when I sat down to see it. It is certainly a strange film to try and get a fix on. At the outset, it would appear that Bujalski has conducted the offbeat endeavour of making a film about the early day of computing – the setting is a conference at unspecified time in the late 1970s where various design teams are competing with computer programs they have designed to play chess against each other.

Initially, the film gives the appearance of being shot as a mockumentary/Found Footage film as though being recorded by an actual documentary/tv crew of the day – where Andrew Bujalski has shot the entire film on VHS tape and in black-and-white (apart from a single scene at the end that inexplicably bursts into colour). However, the mockumentary approach is intermittent as clearly some of the scenes are ones that could not be taking place with a cameraperson present.

Bujalski gets the period down right – all the hairstyles and moustaches, the bulky oversized computers of the day where activating a program comes via typed command line input and such a thing as a graphic user interface and a mouse don’t yet exist, where the lectures come with transparencies on an overhead projector rather than a PowerPoint presentation and the leading font type of the day is Courier. The film’s documentary-like approach and the chatter among the geeky fraternity of engineers, even their wowed fascination at the first girl to attend the conference, all feels authentic.

You wonder though what dramatic possibilities a film that sets out to replicate a computer chess convention from the 1970s, consisting of geeks talking tech, inputting data into computers and machines playing chess offers. Chess is largely an abstract game and is never one that any film has managed to exploit for much in the way of drama – at least in the same way that say baseball or basketball has held much potential for filmmakers – unless perhaps you want to count the climax of The Black Cat (1934).

As a result, Bujalski never engages much with any of the games of chess dramatically. Rather the focus is all on the quirks of the people at the conference and the engineering anomalies that arise. A more commercial type of film would have spent more time characterising the various players, cheering one side on and concentrating on the tension/rivalry between teams in the build-up to the culminating round, but Bujalski is more interested in just offering detached slices of observation of the various characters.

It is here that Computer Chess starts to get strange. Bujalski has fun charting the quirks of some of the players – in particular, the character of the highly opiniated Michael Papageorge (Myles Paige) who spends much of the film trying to find a room in which to crash after finding he doesn’t have one due to a booking error (and an equal amount seemingly engaged in dubious activities where the film never makes it particularly clear what is going on); Peter Bishton (Patrick Riester), a teen geek with some social awkwardness issues who has a rather funny encounter with a couple of middle-aged swingers; or the computer programmers constantly bumping into attendees at an EST/rebirthing-styled conference also taking place in the hotel.

On the other hand, I wasn’t particularly sure where Andrew Bujalski was going with all of this. He seems to be aiming for a quirkily offhand depiction of the various people – I was reminded of the characters sketches you get in a Wes Anderson film but in a less deadpan and consciously weird way. If you were to pigeonhole the film, you might consider it something akin to Darren Aronofsky’s Pi (1998) or maybe Primer (2003) as worked over by Wes Anderson.

I kept wanting to follow these stories as the quirkiness of humour at play seemed to hold some of the most interesting parts of the film but more than anything they seem like half-constructed pieces of story where Bujalski could never be concerned whether they ended up going anywhere. There is a scene at the end where Papageorge visits his mother with one of the attendees and becomes frantic about trying to find a box of money he has left but the significance of the money and the box is never made clear.

This puzzlingly ragged tapestry of story ends becomes even more confusing when Computer Chess starts to become a science-fiction film. There are the fascinating scenes where Patrick Riester puzzles over the fact that his computer program is making irrational moves and then comes to the realisation that it is demonstrating a preference for playing with humans rather than computers and starts to wonder if it is demonstrating intelligence. There is an even stranger scene near the end where Wiley Wiggins tells in flashback how he started asking the computer a series of metaphysical questions about whether it had a soul and it replied with its own questions before offering up a brief flash of an ultrasound picture of a womb.

Here Bujalski seems to be wanting to alight on the debate about artificial intelligence, although I am not entirely sure if he does it in any informed way. It does seem rather absurd to be start talking about artificial intelligence and independent thought in bulky computers back in the day of 264k memory, before GUI interfaces, mice and the internet. More than anything you feel that maybe Andrew Bujalski has maybe inhaled a little too much of Raymond Kurzweil, Vernor Vinge and their theory of The Singularity.

Even more baffling is the film’s final scene [PLOT SPOILERS] where Patrick Riester picks up a hooker that has been lurking around outside the hotel and takes her to his room where she strips and then in the final image takes off her wig revealing a head filled with circuitry. Quite what this means is baffling. With films like Pi and Primer, you get a fascinating conceptual mystery that hints at a greater breakthrough of understanding, whereas with Computer Chess you feel like you have watched a film that feels like a baffling series of non-sequitir plot constructs. If nothing else, it is one of the few films that you can see you are still mentally going back over a few days later examining it for meaning to see if you have missed anything.

Andrew Bujalski abandoned the mumblecore style with his next films results (2015) and Support the Girls (2018). The oddest credit on his resume is the screenplay for the remake of Lady and the Tramp (2019).

Trailer here