Crew

Director – Adam Nimoy, Producers – Joseph Kornbrodt, Kevin Layne & David Zappone, Photography – Kevin Layne, Music – Nicholas Pike, Animation Supervisor – Josh Novak. Production Company – 455 Films.

With

J.J. Abrams, Jason Alexander, Mayim Bialik, Marty Dormany, James Duff, Bobak Ferdowsi, Dorothy Fontana, Catherine Hicks, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Walter Koenig, Amy Mainzer, Adam Malin, Scott Mantz, Nicholas Meyer, Adam Nimoy, Julie Nimoy, Mel Nimoy, Sybil Nimoy, Jim Parsons, Simon Pegg, Chris Pine, Bill Prady, Zachary Quinto, Zoe Saldana, Aaron Bay Schuck, Ben Shaktman, William Shatner, George Takei, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Karl Urban

For the Love of Spock is a documentary about the life of Leonard Nimoy (1931-2015), the actor who needs little introduction for his fame in the role of the logical half-alien Mr Spock on the tv series Star Trek (1966-9). The documentary is directed by Nimoy’s son Adam and was released the year after Nimoy’s death in time for the celebration of Star Trek‘s fiftieth anniversary.

The documentary starts out with discussion of Nimoy’s childhood and upbringing in Boston, mentions of his early jobs where he was trying to make ends meet – everything from vacuum-cleaner salesman, fishtank salesman to cab driver – and then his early acting experiences. We get to see clips from many of his early roles, mostly in television – although oddly none of his early bit parts in science-fiction films such as Zombies of the Stratosphere (1952), Them! (1954) and The Brain Eaters (1958).

Nimoy was cast by Gene Roddenberry in the Star Trek pilot The Cage (1966) after he was spotted in a role on Roddenberry’s previous tv series The Lieutenant (1963-4). At Roddenberry’s insistence, Nimoy was the one holdover when NBC ordered a second pilot but that the entire cast from The Cage be dumped. The most interesting sections of the film come in the tracing of the evolution of Spock. It may surprise some but Spock never came out as a pre-conceived character. In The Cage, he was far more emotional – as Nimoy recounts in archive footage, that was in response to Jeffrey Hunter who was a far more internal and reserved actor; when the captain’s role was inherited by William Shatner in the series, Nimoy played up the emotionlesness as counter to Shatner’s gregariousness and energy.

I was aware of the story of how Nimoy created the idea of the Vulcan Nerve Pinch as a pacifist response to a script that called him to subdue an attacker by hitting him with the butt of a gun. That is repeated here and we learn other aspects of how Spock’s trademark “fascinating” came about from Joseph Sargent, the director of the episode The Corbomite Maneuver (1966), who suggested that Nimoy play the part as a curious and detached scientist rather than reacting to the cry for battle stations like the rest of the crew.

In archive footage, Nimoy talks of how he created the Vulcan salute (with the second and third fingers of the hand spread apart in a V) after seeing it used as a ritual blessing by the priests in the synagogue growing up. One of the more fascinating aspects is where an interviewed Nimoy (again archive footage) talks of being inspired by a live performance by Harry Belafonte who made little movement for the first few songs of the set, resulting in an electrifying effect when he finally did raise his hands and how this same minimalism of movement inspired him to turn something as simple as the curling of an eyebrow into a dramatic effect.

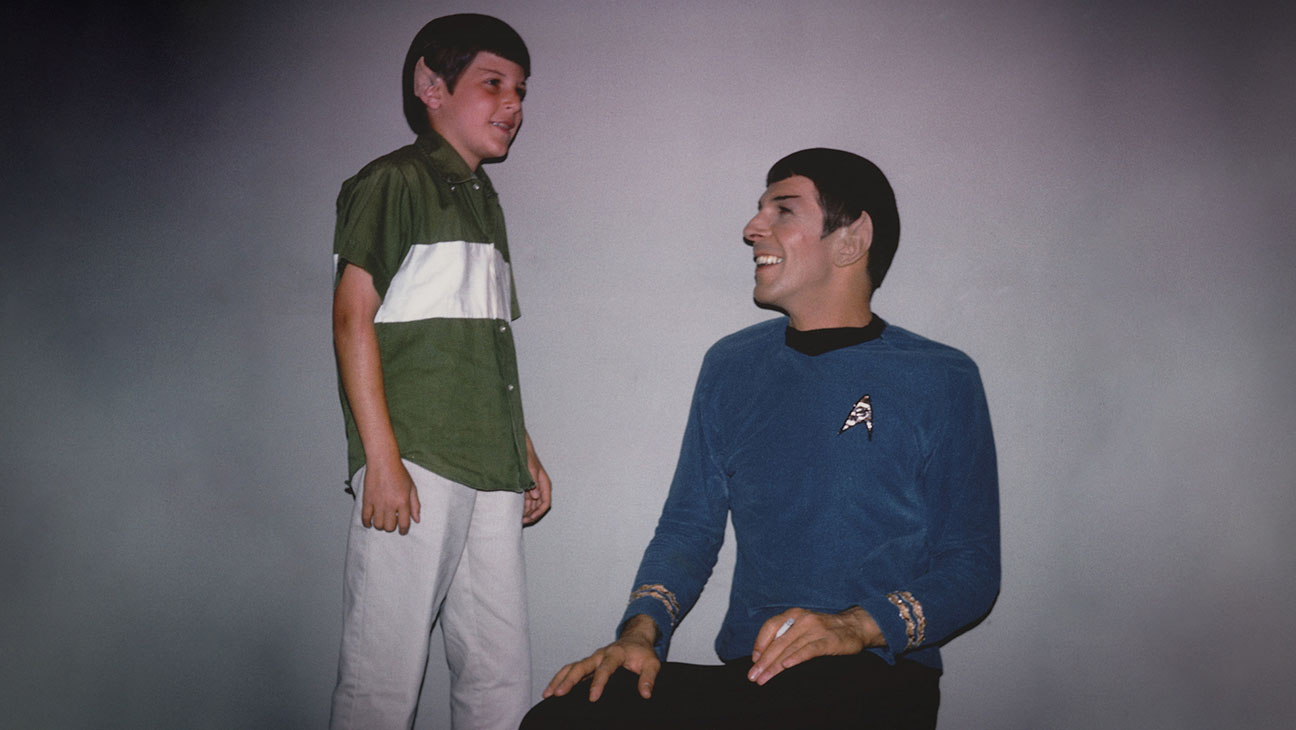

The documentary discusses the effect that the unexpected popularity of Spock had on Nimoy and family – especially in that Nimoy’s name and address was listed in the phonebook resulting in numerous fans turning up to visit, or of the increasingly unwelcome intrusions made into family life by press and photographers. The documentary moves from the end of Star Trek to Nimoy’s three year stint on Mission: Impossible (1966-73) and into theatre in the 1970s doing what many call some of his best work. The documentary does briefly dip into some of his ventures into recording during this time, including showing a video clip from the embarrassing The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins (1967), although does not mention Nimoy’s books of poetry or his two autobiographical books I Am Not Spock (1975) and I Am Spock (1995). We do however get some mention of his sideline as a photographer (although Adam seems a little coy about bringing out the fact that much of this was nude photography).

The documentary then moves on to discussion of the Star Trek feature film revivals. One of the more fascinating aspects for me is finally finding why Nimoy held out from signing back on to the first film Star Trek – The Motion Picture (1979). I had often assumed that this was due to his not wanting to be associated with the role but instead we find out in Nimoy’s own words that it was all down to his discovering that Paramount had repeatedly been using his likeness in the selling of Star Trek merchandise without paying him any royalties and had launched a lawsuit against them. He held out from signing onto the film as leverage for them to settle – one of the more interesting facts is that the lawyer sent to negotiate with him was a young Jeffrey Katzenberg, later famous as a chairman at Disney and one of the co-founders of DreamWorks.

Nimoy also calls The Motion Picture terrible, saying that it was all effects and little focus on the characters. Which I find kind of interesting as I have always regarded The Motion Picture as one of the better Star Trek films (albeit a minority position) but this does point the way forward to Nimoy’s assumption of the director’s chair with Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984) and The Voyage Home: Star Trek IV (1986), which marked the films– move away from boldly going adventures to an emphasis on the ensemble of familiar characters, which quickly became synonymous with a pandering to fan nostalgia.

The final section deals with the rapid decline of Nimoy’s career as a director during the 1980s, going from the hits of the Star Trek films and Three Men and a Baby (1987) to the flop of The Good Mother (1988). (His final directorial film Holy Matrimony (1994) is not even mentioned). The documentary deals somewhat with Nimoy’s personal issues after that point – a struggle with alcoholism, a divorce from his wife of thirty plus years and subsequent marriage to Susan Bay (the cousin of Michael).

The final section skips over the 1990s and 2000s to his cameos in Star Trek (2009) and Star Trek: Into Darkness (2013). The Nu Trek films get far too much emphasis for my liking, given their trashing of the spirit of the original series and dislike by many fans. Here we get interviews with everyone from J.J. Abrams, Chris Pine, Simon Pegg, Zoe Saldana, Karl Urban and Zachary Quinto (in fact, far more people than the number of interviewees representing the original series). What the documentary skips over entirely is Nimoy’s work elsewhere during these two decades – his ongoing guest role in the J.J. Abrams tv series Fringe (2008-13), even if you like his spoof appearances on The Simpsons (1989– ) and Futurama (1999-2002), not even mention of his celebrated reappearance as Spock in the two-part Star Trek: The Next Generation episode Unification (1991).

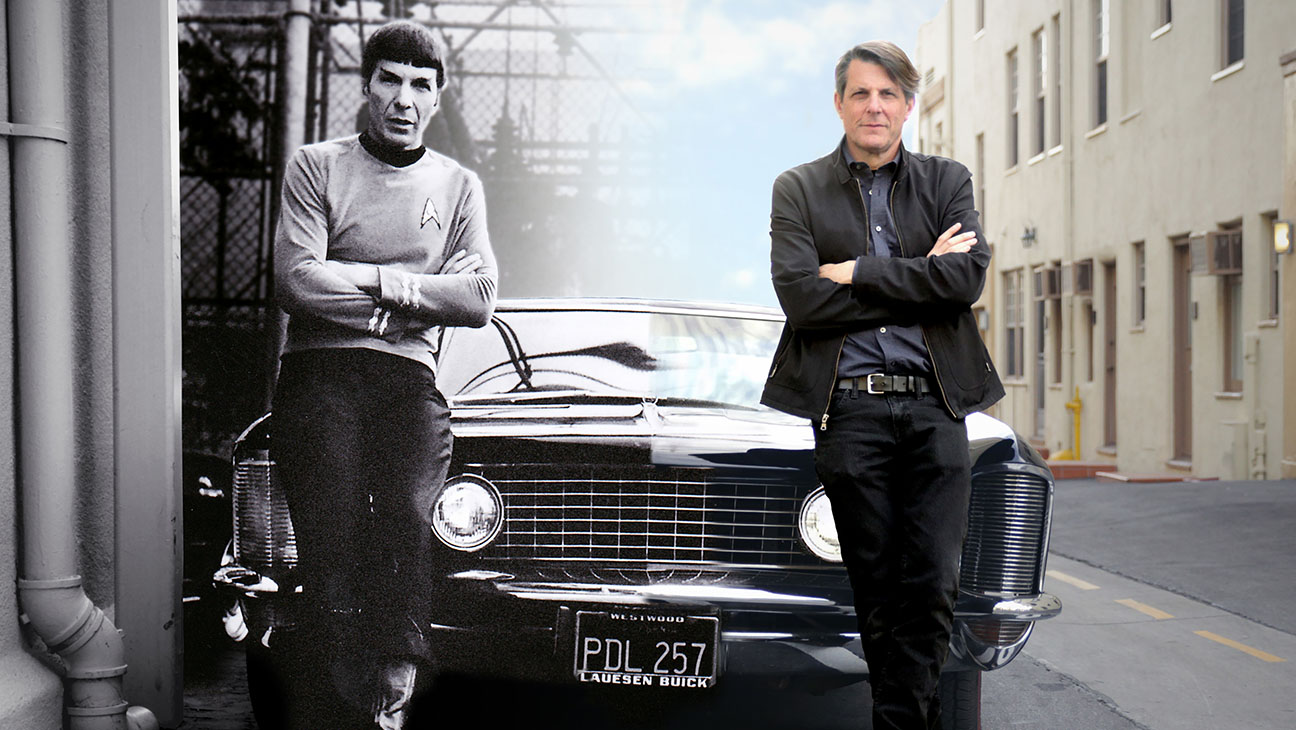

Adam Nimoy keeps the story of his father as a straightforward biography for the most part, although there are undeniable times when the personal slips in. There are brief mentions of the rift between the two of them during the 1970s where Nimoy clearly disapproved of Adam becoming what he describes as “a full-fledged Deadhead” and the accompanying pictures show him having joined the counter-culture movement. Curiously, it is only now reaching the age of sixty that Adam Nimoy attends his first Star Trek convention. (Although I suppose this is not too much of a surprise given that the Star Trek conventions did not begin until the early 1970s when Adam was in his twenties and father and son had started to drift apart). This does mean that what we are getting is a documentary by somebody who, even though he is a blood relative of Nimoy, comes to the Star Trek fan phenomenon as an outsider. One of the more amusing moments is when Adam cautiously dips his toes into the arena of slash fandom and embarrassedly raises the issue in front of George Takei – because who else would you discuss it with but the gay man (even though slash is less an LGBT phenomenon than something that is created and consumed by heterosexual women).

The rift between Nimoy and Adam comes to the fore at the end of the film. Adam never delves into what the issues it centred around were about (although I don’t begrudge him keeping his personal affairs out of the film). This does however bring For the Love of Spock to a moving end where Adam talks to Zachary Quinto about his marriage to his second wife Marcia only for her to die eighteen months later and how his dealing with such forged a reconciliation with his father after a four-year gap.

Adam Nimoy does briefly dwell on how his father encouraged him to leave behind his career as an entertainment lawyer and became a director. The only of his works mentioned here is The Outer Limits episode I, Robot (1995) where both Nimoys worked together. Adam does however have an impressive range of credits on various other tv series including episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94), NYPD Blue (1993-2005), Hercules: The Legendary Journeys (1994-9), Sliders (1995-2000), Nash Bridges (1996-2001), Ally McBeal (1997-2002), The Practice (1997-2004) and Gilmore Girls (2000-7), among others. For the Love of Spock, which was made with a Kickstarter-raised budget, was his first feature film.

Trailer here