USA. 2005.

Crew

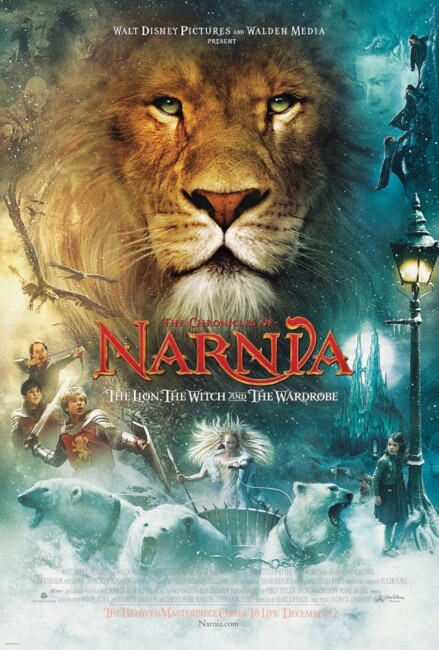

Director – Andrew Adamson, Screenplay – Andrew Adamson, Christopher Markus, Stephen McFeeley & Ann Peacock, Based on the Novel The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) by C.S. Lewis, Producers – Mark Johnson & Philip Steuer, Photography – Donald McAlpine, Music – Harry Gregson-Williams, Visual Effects Supervisor – Dean Wright, Visual Effects – Digital Dream VFX, Gentle Giant Studios, I.C.O. Entertainment Inc, Industrial Light and Magic (Supervisor – Scott Farrar), Rhythm and Hues (Supervisor – Bill Westenhofer), Sandbox Pictures, Soho VFX, Sony Pictures Imageworks (Supervisor – Jim Dersey), Studio C, Svengali Studio, Weta Workshop (Supervisor – Richard Taylor), Miniatures – New Deal Studios Inc (Supervisor – Ian Hunter), Special Effects Supervisor – Katrina Stephens, Makeup Effects – K.N.B. EFX Group Inc, Production Design – Roger Ford. Production Company – Disney/Walden Media.

Cast

Georgie Henley (Lucy Pevensie), Skandar Keynes (Edmund Pevensie), William Moseley (Peter Pevensie), Anna Popplewell (Susan Pevensie), Tilda Swinton (The White Witch Jadis), James McAvoy (Mr Tumnus), Liam Neeson (Voice of Aslan), Ray Winstone (Voice of Mr Beaver), Dawn French (Voice of Mrs Beaver), Jim Broadbent (Professor Kirke), Kiran Shah (Ginarrbrik), James Cosmo (Father Christmas), Rupert Everett (Voice of Fox), Patrick Kake (Oreius), Elizabeth Hawthorne (Mrs MacReady), Judy McIntosh (Mrs Pevensie)

Plot

The four Pevensie children, Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy, are sent away from the Blitz in Wartime London to stay with the eccentric Professor Kirke in his large country mansion. While playing hide’n’seek, Lucy discovers a wardrobe and enters, passing through the other side to find herself in a snowbound forest. She meets a faun Mr Tumnus, who invites her for tea and explains that she is in the land of Narnia. However, when Lucy returns through the closet and finds that no time has passed, the others ridicule her story. She returns through the wardrobe in the middle of the night and is followed by Edmund. Edmund encounters the White Witch who rules the land and refuses to allow Christmas to come. The White Witch tempts Edmund with the promise of Turkish Delight if he will bring the others through the wardrobe. Fleeing after they knock a cricket ball through a window, the four children hide in the wardrobe and discover Narnia. Once they are there, the White Witch seeks to kill them in order to prevent a prophecy that says the coming of four kings and queens will spell her end. Edmund returns to the Witch seeking his reward, only to be made her prisoner. The others place their trust in the mighty lion Aslan, the lord of the forest, who has now returned to marshal the creatures of the land to stand up against the forces of the White Witch.

It is safe to say that if there had not been the success of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy – The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002) and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) – there would be no The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe looks exactly like studios, in their rush around to find other properties to exploit the newfound boom in high fantasy, had alighted on the C.S. Lewis Narnia books as eminently filmable. (Not to mention that the seven book Narnia series has much potential to be spun off an ongoing franchise).

The connections between Lord of the Rings and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe go much further than mere imitation. The original authors of The Lord of the Rings and the Narnia books – J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis – were both good friends at Oxford. Tolkien and Lewis encouraged and critiqued one another in their writing endeavours, formed a writing group The Inklings, and even at one point collaborated on a never-completed writing project.

The associations also extend to the films of Lord of the Rings and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, which both draw upon (or seek to draw upon) a New Zealand connection. With Lord of the Rings, Peter Jackson put New Zealand on the map in terms of major filmmaking (and tourism) and enjoyed extraordinary success. The people behind The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe clearly also sought to exploit this connection. The director chosen for The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was Andrew Adamson. Andrew Adamson is a New Zealander who began in the film industry in the visual effects department at Pacific Data Images, working on Joel Schumacher’s two Batman atrocities Batman Forever (1995) and Batman & Robin (1997), among others, before graduating to co-director of DreamWorks’ hit animated film Shrek (2001) and its sequel Shrek 2 (2004). Andrew Adamson brought the entire production of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe home to New Zealand to film. Clearly, in allowing him to do so, Disney seemed to think they could exploit whatever association that New Zealand had had in the public mind with The Lord of the Rings and Peter Jackson. Even further than that, Adamson managed to employ a number of people from Jackson’s team, most notably the Oscar-winning effects and creature design whiz Richard Taylor and his Weta Workshop team.

While it was the triumph of The Lord of the Rings that allowed The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to get off the ground, the film that almost certainly influenced The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, at least when it came to the marketing, was the massive success of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004). Gibson made The Passion of the Christ independently as a work of personal faith. Against predictions, the film became a runaway sensation. What the success of The Passion of the Christ clearly identified was that Christians made up a substantial percentage of the audience in the American heartland evangelical. The Passion of the Christ suddenly opened up a new market as far as Hollywood was concerned and created the notion of marketing campaigns that stepped around the usual routes (newspapers, tv, internet and theatrical trailers) and pitched and even previewed the films in churches to Christian audiences. It was this marketing strategy that propelled the utterly mediocre The Exorcism of Emily Rose (2005) to become a box-office hit.

This strategy has also been employed when it comes to The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Here Disney employed a dual level marketing strategy where they cannily pitched The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe to mainstream audiences as a fantasy film in the same vein as The Lord of the Rings, while devising another entire strategy that promoted, previewed and distributed materials in churches across the world, playing up the Christian allegory aspect of the story. Indeed, this dual marketing stream, each seemingly independent of the other, was so successful that you could not find a single piece of mainstream promotion about The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe that in anyway told you about the Christian allegory aspect or even C.S. Lewis’s background as a writer on Christian matters.

On the other hand, one is left wondering whether Disney’s stratagem is one that actually works. In playing the New Zealand connection card, one wonders what it is (aside from some of the exceedingly generous tax breaks that the government granted big-budget filmmakers following Peter Jackson’s success) that Disney imagined they would get from the country excepting hoping maybe that some of the mana the country held for Peter Jackson might rub off on their film too. One cannot help but wonder if Andrew Adamson would have ended up as the director of $180 million budget film like this had he not had a Kiwi passport and had Peter Jackson not been there before him. After all, Adamson was an animation director who had never worked with live-action actors before steeping onto the set of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Adamson was one of the co-directors on Shrek, which was a huge audience hit, but when he was the only of the two directors of the first film to return for Shrek 2, all of the humour of the original seem to collapse into cute, self-congratulatoriness.

And for all their eagerness to be regarded as a new market niche for mainstream filmmakers, these church-based marketing strategies make one wonder about the faith of the Christians that embrace these movies – there does seem something oddly dubious in allowing one’s faith to be exploited by secular market campaigners whose only desire is to sell movie tickets. And beneath all of this when one looks at the films in question, there does seem something hypocritical. Christian groups have been extremely active in trying to have the Harry Potter books regarded as ungodly because they supposedly promote an interest in the occult, yet when a similar kind of fantasy is wielded here it suddenly becomes something suitable to be marketed to the mainstream; the same groups have been heavily condemnatory of horror films, yet when the same clichés and theatrics are employed in a film like The Exorcism of Emily Rose, the film is suddenly perfectly acceptable to be screened in churches because it is made by a Christian; the same groups are condemnatory of gore and splatter films and certain that they cause violence to happen in real life, yet when The Passion of the Christ was released with an R-rating because of its level of gore and splatter, the same groups protested to the ratings boards at the unfairness of the system in not allowing the film to be shown to children.

C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) is an interesting figure. Born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, Lewis came to England at an early age. After serving in the trenches in World War I, Lewis graduated from Oxford and became a professor of Mediaeval and Renaissance Literature at Magdalene College in Cambridge. The crucial event in C.S. Lewis’s life came with his conversion to Christianity in 1929, following suasion by seemingly incontrovertible argument from his peers (which apparently included his good friend J.R.R. Tolkien). Soon after this, Lewis began publishing with The Pilgrim’s Regress (1933), which was an account of his conversion.

For those who come to C.S. Lewis as a writer of fantasy, it is some surprise to learn of the greater context of his writing – namely almost everything that he published – be it fiction or his considerably larger body of non-fiction – is concerned with matters of Christian faith. These range from works of fiction like The Screwtape Letters (1942) and The Great Divorce (1945), which are debates about matters of the soul and damnation; the trilogy Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1943) and That Hideous Strength (1946) – a science-fiction series that takes place on Mars where the Fall from the Garden of Eden never occurred; and Till We Have Faces (1956), a retelling of the myth of Cupid and Psyche that manages to wind in matters Christian; to works of non-fiction Christian apologetics such as The Problem of Pain (1940), Miracles (1947), Mere Christianity (1952) and Surprised by Joy (1952), among many others.

However, C.S. Lewis will always be remembered for his Narnia children’s books, which consist of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950), Prince Caspian (1951), The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952), The Silver Chair (1953), The Horse and His Boy (1954), The Magician’s Nephew (1955) and The Last Battle (1955). In understanding C.S. Lewis, one must realise that the real context of the Narnia books is not so much their appeal as fantasy stories, but rather that Lewis wrote them as allegorical tales preaching aspects of Christianity in the guise of children’s stories. Thus, the lion Aslan is an analogue of Jesus Christ; the White Witch represents Satan; and Edmund’s temptation by Turkish Delight is about sin. The subsequent Narnia books took up various other aspects of faith, which became increasingly more explicit as the series went on with Lewis eventually writing allegorical versions of The Books of Genesis and Revelations and creating figures that were crude caricatures of atheists and rationalists. The Narnia books have been increasingly criticised in the modern era for containing elements that are racist and sexist and for their implicit class assumptions.

The Narnia books had previously been filmed by the BBC as three mini-series – The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch, & the Wardrobe (1988), The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian (1989), The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1989) and The Chronicles of Narnia: The Silver Chair (1990). The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe had also been previously filmed in a ten episode live-action tv series The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1967) and as an animated tv movie The Lion, The Witch & the Wardrobe (1979).

In various discussions prior to the opening of the The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, I realised that people who had read the Narnia books fall into three camps – those who had read them as Christian works because they were believers; those who had read them as children and enjoyed them unaware of any religious allegory; and those who had discovered the real nature of the stories and switched off after realising that they were being preached to. Andrew Adamson deliberately avoided commenting on any aspect of the Christian allegory in interviews and would at least appear to be making the film from the point of view of someone in this second category – a person who simply enjoyed the books as a child.

This makes writing about The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe difficult – more than once one has been urged to view the film as merely a fantasy and to stop trying to see it in any other context. However, this proves impossible – you cannot look at a work and discard the author’s original intentions – and even if one did so, the ardent zeal of Christian evangelicals to accept The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe as theirs and Disney to market the film to Christian audiences, makes this aspect of the film impossible to ignore. Certainly, the Christian allegory is something that is never particularly overt in the film, although there are undeniably times that make you wonder about Andrew Adamson’s lack of interest in such – like the scene of Aslan’s resurrection and the breaking of the Stone Table as the two girls lie over his dead body, which contains unmistakeable resonances of Mary and Mary Magdalen witnessing Christ’s resurrection from the tomb.

For all the hype surrounding the film, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe emerges as little more than Lord of the Rings Lite. Certainly, the children give reasonable performances, especially Georgie Henley as Lucy, and come across a good deal more likeably than they did in the 1988 BBC tv version. Alas, the problem with The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is Andrew Adamson himself. Perhaps it is Adamson’s inexperience as a live-action director, but the film seems infected with a blandness. Part of this seems to lie in the film’s deliberate pitch to family entertainment – that nothing be regarded as too scary, that no real blood or death be shown. However, this also extends to the characters who seem dreadfully nice but have little depth beyond what is brought by the actors inhabiting them on screen.

The location work is expectedly lovely, even occasionally lavish, but The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe never particularly flies as a fantasy film. Andrew Adamson aims for, but crucially fails to achieve, the epic flourish that Peter Jackson gave The Lord of the Rings. There is nothing in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe that holds the sheer thrill and exhilaration of sequences like Gandalf’s facing the Balrog on the Bridge of Khazad-Dûm in The Fellowship of the Ring or the Battle of Helm’s Deep in The Two Towers. Adamson tries hard, but a sequence like where the children face the wolves on the melting icepack of a river falls completely flat – the sequence seems contrived in its drama and the end with children riding out on a shard of ice seems entirely unconvincing, even faintly laughable. The climactic battle sequence does array some visually impressive scenes of armies lined up and various mythical creatures engaged in combat, but none of it comes with a sense of awe or dramatic enthrallment.

For all the substantial amount of money that has been lavished on The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and Andrew Adamson’s background in visual effects, there are times that the effects look tatty. The central character of Aslan is certainly highly convincing, but the beavers look like no more than B-budget CGI effects, while the makeup job on the White Queen’s dwarf assistant Ginnarbrik is thoroughly unconvincing.

One came away feeling that The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe should have moved one but that Andrew Adamson through inexperience, lack of ability to command actors or whatever failed to deliver it – there, for instance, seems surprisingly little tragedy in any of the scenes of Edmund’s corruption and especially in the sacrifice of Aslan, which after all is supposed to be the equivalent of Christ’s death on the cross. Instead, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is merely a nice film that produces some effects that look pretty, but fail to move on any more substantial a level. Indeed, for all its impoverishment of budget, the BBC adaptation of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe managed to hold together with more dramatic effect than the film here does.

All principal parties involved teamed up again for The Chronicles of Narnia: Prince Caspian (2008), followed by The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (2010). The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe was parodied in Epic Movie (2007).

After directing Prince Caspian, Andrew Adamson next went onto Cirque du Soleil: Worlds Away (2012) and the non-genre Mr Pip (2012).

Walden Media, the Christian-based production company that co-produced The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe with Disney, went onto make a number of other fantasy, many of these containing Christian messages pitched to family audiences. Walden Media’s subsequent films include the remake of Charlotte’s Web (2006), Bridge to Terabithia (2007), Mr Magorium’s Wonder Emporium (2007), The Seeker: The Dark is Rising (2007), The Water Horse (2007), City of Ember (2008), Journey to the Center of the Earth 3D (2008), Nim’s Island (2008), Tooth Fairy (2010), The Giver (2014), A Dog’s Purpose (2017), The Star (2017), Dora and the Lost City of Gold (2019) and A Babysitter’s Guide to Monster Hunting (2020).

Trailer here