Crew

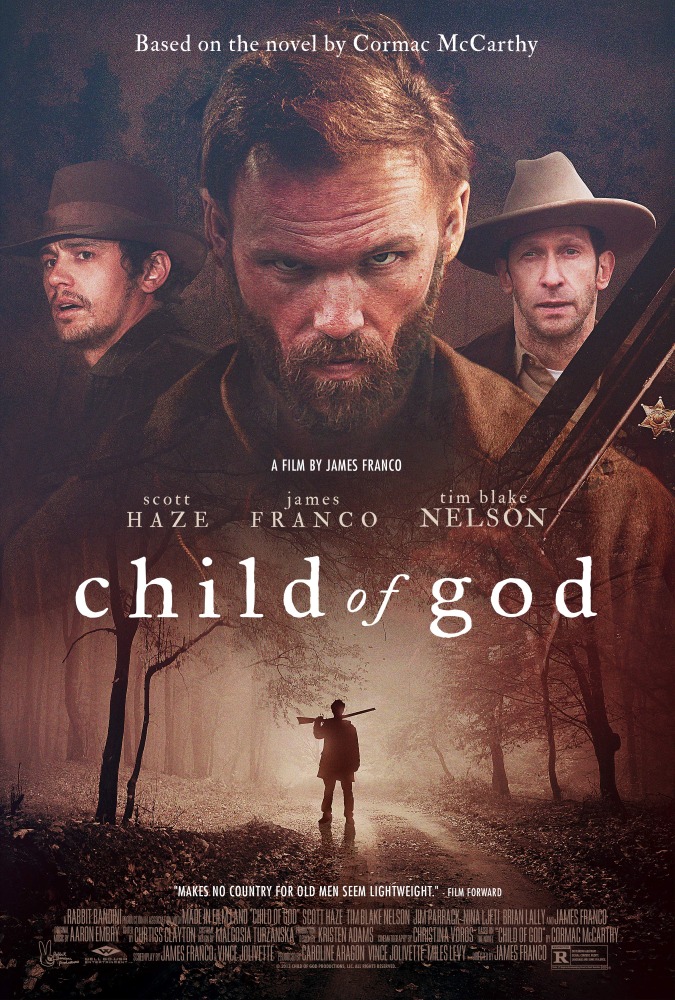

Director – James Franco, Screenplay – James Franco & Vince Jolivette, Based on the Novel Child of God (1971) by Cormac McCarthy, Producers – Caroline Aragon, Vince Jolivette & Miles Levy, Photography – Christina Voros, Music – Aaron Embry, Special Effects Supervisor – Brian Merrick, Makeup Effects – Ginger Basham-Workman & Dustin Blankenship, Production Design – Kristen Adams. Production Company – Rabbit Bandini Productions/Made in Film Land.

Cast

Scott Haze (Lester Ballard), Tim Blake Nelson (Sheriff Fate Turner), Jim Parrack (Deputy Cotton), Elena McGhee (Lady in White), Nina Ljeti (Victim #1), Brian Lally (John Greer), Ciera Parrack (Salesgirl), Joseph Wallace (Prisoner)

Plot

Sevierville County, Tennessee in the 1950s. The mentally ill Lester Ballard tries to drive away at gunpoint the townspeople who have foreclosed and are auctioning off his family property. Beaten and tossed off the land, Lester goes to live in an abandoned cabin in the woods, hunting for food and wandering in mind. He comes across a woman in the woods and tries to help her. He is then taken in by the sheriff’s department as she falsely presses rape charges against him. Released, he returns to the woods. There he comes across a car with two young lovers inside, having killed themselves with carbon monoxide. He takes the girl’s body to his cabin and tries to maintain the pretence of a relationship, only to accidentally burn the cabin down. From there, Lester moves to killing other people making out in parked cars and taking the bodies of the women with him to a cave in the woods.

James Franco is largely known as an actor. First appearing in the late 1990s, he blossomed on tv’s Freaks and Geeks (1999-2000) and then as Harry Osborn in Spider-Man (2002) and sequels. Franco has gone on to a number of appearances in A-list films including Tristan + Isolde (2006), Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) and Oz: The Great and Powerful (2013), while accruing serious acclaim for dramatic works like Milk (2008) and Howl (2010), even an Academy Award nomination for 127 Hours (2010) and various Sexiest Man Alive titles. At the same time as his star rose to A-list status, rather than capitalising on it, Franco seems to be wanting to kick back and have fun, having joined the Judd Apatow-Seth Rogen club with roles in films like Pineapple Express (2008), Your Highness (2011), This is The End (2013) and The Interview (2014).

What is frequently overlooked in Franco’s superstar status is that he is a multi-disciplinary talent. He has published a collection of short stories and released two albums of music. He is also less recognised as a director, despite Child of God being no less than his thirteenth full-length film. Moreover, Franco chooses subject matter that is off the beaten track and decidedly non-commercial. Following his first full-length effort The Ape (2005), a comedy about a man with a talking ape flatmate, most of Franco’s work has been in the letters – The Broken Tower (2011), a documentary about the poet Hart Crane; Sal (2011), a dramatisation of the life of murdered actor Sal Mineo; adaptations of William Faulkner with As I Lay Dying (2013) and The Sound and the Fury (2014); Bukowski (2013), a biopic of the poet and writer; Tenn (2015) about the young Tennessee Williams; the John Steinbeck adaptation In Dubious Battle (2016); and The Disaster Artist (2017) about the making of the bad movie classic The Room (2003). And then there have been those that are downright eccentric and about as non-commercial as it is possible to get – My Own Private River (2012), which makes Gus Van Sant’s outtakes from My Own Private Idaho (1991) into a tribute to River Phoenix; and Interior. Leather Bar (2013), a reimagining of the missing 40 minutes of hardcore gay scenes that were cut from William Friedkin’s Cruising (1980). In genre material, Franco has also directed the quasi-historical The Institute (2017) about secret societies and abuse at an insane asylum; and the post-holocaust set Future World (2018).

In his preference for literary works, Franco here turns his attentions to one of the greatest of contemporary American writers Cormac McCarthy. McCarthy’s name has risen a good deal in the last few years with the film adaptations of No Country for Old Men (2007) and The Road (2009), as well as his original screenplay for Ridley Scott’s The Counselor (2013), which was a far better film than the mediocre reception it received. McCarthy has however been writing back to 1960s. McCarthy’s writing is extraordinary – and in ways that no film adaptation has done justice. It comes with extraordinary turns of phrase when it comes to describing states of mind, qualities of character or in sketching the landscape, all delivered without quotation marks or much in the way of punctuation. McCarthy’s subject matter delves into dark and extreme places, his worlds are violent and swim in Old Testament allegory. Pick up a McCarthy novel, read but a single page and I defy one not to be blown away by the vividness of the writing and imagery.

Like Ray Bradbury (and William Faulkner), Cormac McCarthy seems a writer doomed to poor treatment on the screen simply because there is no way to express on film what he writes, which lies less in the happenings in the plot and more in the internal spaces of the characters and the description of the landscapes. Through no fault on the part of James Franco’s effort, this is the problem that Child of God is stuck with. We do get a few sections of McCarthy prose used as chapter headings between the sections but this hardly compensates. What the film feels more like is a study notes summation of the main plot elements of the book. Franco – at least from what I can tell watching him at work in Interior. Leather Bar – is very much an improvisational director who directs not unlike Terrence Malick and lets the film form out of the way his actors improvise. This seemingly naturalistic, approach would seem to approximate what it is that McCarthy is aiming for.

Child of God (1971) is one Cormac McCarthy novel I have not read. Thus I went into the film fresh, not knowing the story and as a result was not expecting to write Child of God up as a genre film. It is certainly not a work that settles in with easy genre pigeonholing. And yet by about the second act when we see Scott Haze eagerly having sex in the back seat of a car with a girl’s dead body and then taking her away to his cabin and cuddling up beside her, or the third act where it is revealed that he has been killing Lover’s Lane couples around the county and dragging the bodies back to his cave in the woods to become a harem of corpses, Child of God is most certainly in the disturbed place where genre films lie.

Franco remains faithful to the story that Cormac McCarthy told. He is most successful in getting down the flinty parochialism of the characters and the sense of place. You get the impression that he made Child of God on a minimum budget – as such, he never goes overboard on things like the 1950s period, which remains understated (never too obvious beyond the cars). It is a digitally-shot film and rests mostly in the seemingly unrehearsed naturalism of the show. Franco also gives the impression in many of his directed films that he is seeking to ignore the mainstream and make small personal films about subjects that he cares about – to such extent that he flaunts anything approaching name casting in most of these. The biggest name he has here is Tim Blake Nelson as the sheriff, followed by the hardly high-profile name of Jim Parrack who was a regular on tv’s True Blood (2008-14).

Almost every scene of the film features the unknown Scott Haze. Haze plays through a craven cower, his entire dialogue mumbled into an unkempt beard as though through he had ill-fitting dentures that were inhibiting his ability to speak clearly. It is his filthy, bedraggled and incomprehensible mutterings that inhabit the bulk of the film. And yet, though the character is a necrophile and a serial killer, he seems innocent. For Cormac McCarthy, the title of the book was an essential metaphor for how we perceived the character – how no matter how depraved, how socially rejected and isolated someone may be, there is a sense of the divine and the innocent in everyone. Franco remains true to the character in this sense, simply observing and depicting while remaining aloof from any moral judgement of his actions.

Trailer here