Crew

Director – Ralph Murphy, Screenplay – Charles Kenyon, Adaptation – Garrett Fort, Based on the Play The Man in Half Moon Street (1939) by Barré Lyndon, Photography (b&w) – Henry Sharp, Music – Miklos Rozsa, Makeup – Wally Westmore, Art Direction – Hans Dreier & Walter Tyler. Production Company – Paramount.

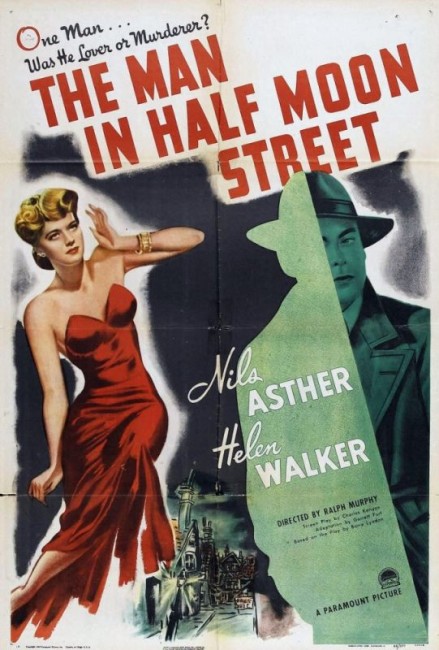

Cast

Nils Asther (Julian Karell), Helen Walker (Eve Brandon), Reinhold Schunzel (Dr Kurt von Bruecken), Paul Cavanagh (Dr Henry Latimer), Edmund Breon (Sir Humphrey Brandon), Matthew Bolton (Inspector Garth), Morton Lowry (Alan Guthrie/Waters)

Plot

In London, Julian Karell has been hired to paint the portrait of Eve Brandon. During the course of doing so, the two fell in love and are planning to announce their engagement to her father as the finished portrait is unveiled. Karell is also engaged in secretive medical research, which he tells Eve is of great importance to mankind. His aging colleague Kurt von Bruecken arrives and they plan to transplant the glands of a student Karell has saved from committing suicide in the Thames. What the rest of society does not know is that though he only looks only in his thirties Karell is over a hundred years old. Many years ago, he and von Bruecken perfected a treatment that halts aging. Karell needs a renewed dose but the aging von Bruecken, who has refused to take the serum, believes that doing so is wrong. Meanwhile, a friend of Eve’s father finds a number of things suspicious about Karell. In going to Scotland Yard to look into these, they discover that Karell has lived a very long time and may have murdered in the past to obtain the glands he needs for his treatment.

The Man in Half Moon Street – not to be confused with the thriller Half Moon Street (1986) with Sigourney Weaver as a hooker – is a classic effort from the heyday of mad scientist cinema. Its pedigree is somewhat higher than the usual mad scientist efforts that were being made at the time, which by the mid-1940s had become extremely cheap efforts that were being made at studios such as PRC and Monogram, mostly starring Bela Lugosi. The Man in Half Moon Street stands outside of this and is notable for lacking many of the regular players that associated with mad science cinema during this decade – Lugosi, Boris Karloff, Lionel Atwill, George Zucco or directors/producers like William Beaudine and Sam Katzman.

The film is based on a play The Man in Half Moon Street (1939) by British-born playwright Barré Lyndon. Lyndon had success with the Broadway play The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse (1936), which was adapted into a successful crime film with Edward G. Robinson in 1938. Lyndon made his screenwriting debut with the Hollywood remake of the Alfred Hitchcock Jack the Ripper film The Lodger (1944) and went onto deliver a number of psycho-thrillers of this era such as Hangover Square (1945) and The Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948). His greatest success came in the 1950s with historical spectacles like The Greatest Show on Earth (1952), Sign of the Pagan (1954) and Omar Khayyam (1957). He is remembered here for his screenplays for the George Pal productions of The War of the Worlds (1953) and Conquest of Space (1955).

You suspect what informs The Man in Half Moon Street is not so much the mad scientist film of the era but the success of the MGM adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1944) the previous year. Both films concern a man who passes amongst polite society and has a secret that he is immortal, where in both the contrast is made between the mask of polite society and the ruthlessness and amorality of the character’s actions. The Man in Half Moon Street works well for the most part. There is a captivating opening where Nils Asther attends a society function and meets an old dowager who finds him familiar, he tells her he is a friend of the man she knew but then describes the illicit rendezvous they had with such detail that she is astonished.

The film is better budgeted than most of the Monogram/PRC cheapies, although is still a B-budget studio effort. Ralph Murphy’s direction is slow and talky. The film is at least written to a far better level than most of the mad scientist efforts of the era, even if in the end it still taps into the same alarmist anti-science stance as these other films – as the aging associate, Reinhold Schunzel seems to have no other role than to decry the experiments with lines like “No man can break the law of God.” It may also be the audience expectation of the era but one feels that the script tries to build up a mystery that is obvious from the outset – that Nils Asther has an immortality treatment. The unsubtly littered clues about the old dowager knowing him, the portrait being identical to another artist’s style, photos of the young Reinhold Schunzel in which Asther is unaged tend to give it away. The film arrives at a cliche end with Nils Asther’s age all catching up with him just as he tries to depart with his love and Scotland Yard closes in.

The Man in Half Moon Street was later remade by Hammer Films as The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959) from director Terence Fisher starring Anton Diffring as the doctor and with Christopher Lee as an associate and Hazel Court as the love interest. There also appear to be at least three adaptations of the play on various live theatre tv shows of the 1940s and 50s, although recordings of all of these are lost. The tv movie The Night Strangler (1973) owes much to the basic premise here, although is a far better treatment of the immortality serum theme.

Trailer here