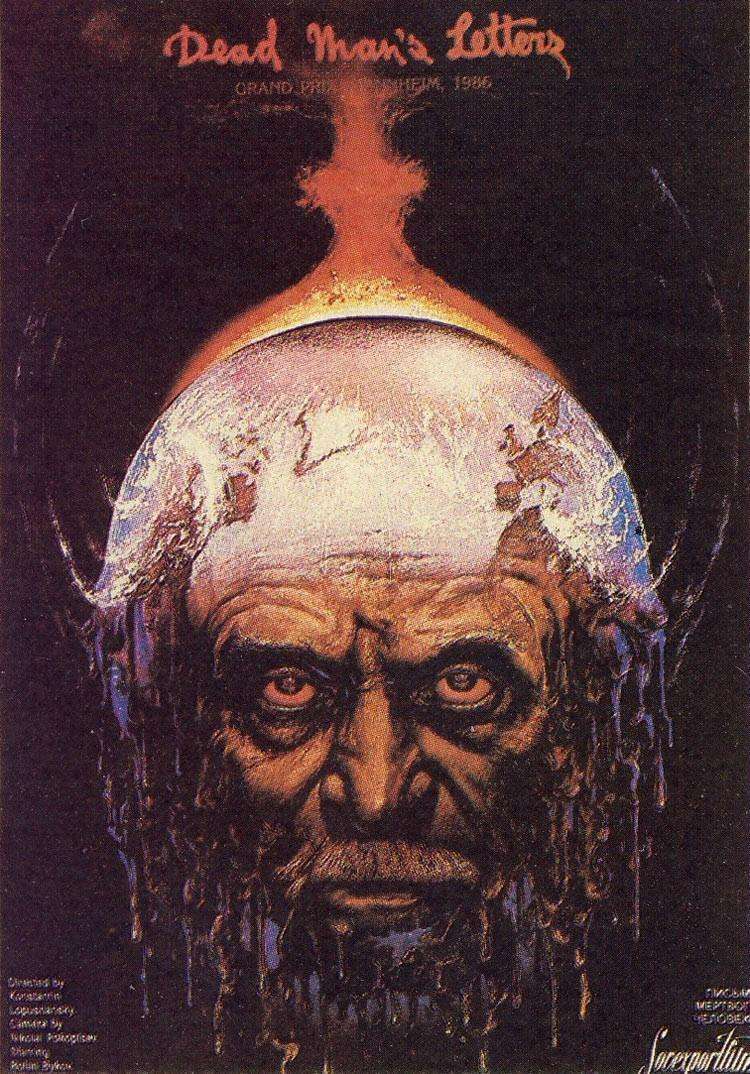

aka Dead Man’s Letters

(Prsma Myortvovo Chelovyeka)

USSR. 1986.

Crew

Director – Konstantin Lopuchansky, Screenplay – Konstanin Lopuchansky, Vyacheslav Rybakov & Boris Strugatsky, Photography (b&w + one scene colour) – Nikolai Pokoptsev, Music – Gabriel Faure, Olivier Messaren & Alexander Zhubin, Art Direction – Yelena Arnchinskay & Viktor Ivanov. Production Company – Lenfilm Studio.

Cast

Rolan Bykov (Professor Larsen), Iosif Ryklin, Victor Mikhailov, Alexander Sabinin, Nora Gryakolova, Svetlana Smirnova, Vera Mayorova, Vatslav Ovorzhetsky, Vadim Lobanov

Plot

Moscow, shortly after the nuclear holocaust. A history professor and several of his colleagues have survived in a fallout shelter beneath the museum where they used to work. The professor spends his time writing a series of letters to his son in the unlikely hope that he is still alive. Amid the surface devastation, the professor finds a group of children who have been struck catatonically mute by the holocaust. Though the city has been placed under rigid militia rule, he attempts to take them away to a place of safety.

Letters from a Dead Man is another film that deals with the theme of the nuclear nightmare. It falls into a mini-genre of nuclear holocaust film along with others such as On the Beach (1959), Dr Strangelove or, How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Fail-Safe (1964), The War Game (1965) et al.

What makes Letters from a Dead Man unique in this case is that the treatment is one that comes from the opposite side of the Iron Curtain. Every single other treatment of the nuclear holocaust theme was made in the West and comes based on the speculation (or at least implication) of what would happen if the bombs falling were coming from the Soviet side; this is one that shows everything from the other perspective.

In both cases though, these films are almost identical in their treatment of the subject matter and are certainly agreed upon what an horrific experience the nuclear holocaust would be. Letters from a Dead Man perhaps comes without the sentimentalised approach of other contemporary 1980s views of the holocaust, as shown in The Day After (1983) and Testament (1983), which related the horrors to the effect on Middle America and the destruction of the family unit. Rather Letters from a Dead Man comes closer to the celebrated pseudo-documentary The War Game in its almost unimaginably bleak depiction of the grim reality of a nuclear blast. Even more so, it is a surprise to see a pre-glasnost film that comes from the heavily state-censored Soviet Union, yet one that manages to be so outspoken against the arms race and moreover rule by military.

Despite the bleakness of the subject, Letters from a Dead Man manages to be an extraordinarily optimistic film. The final image of Rolan Bykov’s professor walking away into the blizzard with the children, “Along as a man walks, he shall have hope,” is a remarkably proffering of humanist faith. There are moments of striking poetry to the dialogue, especially the narrated letters of the professor to his son. This is possibly due to the hand of Boris Strugatsky, who with his brother Arkady was one of the few science-fiction writers in the Soviet Union, the two producing works like Tale of the Troika (1968), Hard to Be a God (1973) and Roadside Picnic (1977), the latter liberally adapted by themselves as Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979).

The detonation of the bomb itself is an image of great beauty – where the detonation of a model cityscape is strikingly contrasted with a soundtrack that only consists of an operatic score and the half-intelligible babblings of a child in the background. There are times when Letters from a Dead Man trips up with the stodgy ponderousness that seemingly dogs all Russian science-fiction films – the scenes with one of Rolan Bykov’s colleagues toasting the nobility of the human race and then sitting in a grave to blow his brains out, or one woman’s lectures on how she can try and spontaneously evolve to live with radiation have a contrarily humorous note to them where it is hard to tell whether the film was approaching things with tongue planted in cheek or not. Most of the film is shot in sepia-tone alternating with a harsh fluorescent blue black-and-white, with the exception of a single colour scene.

The Strugatsky Brothers’ books have produced a number of film adaptations, the most famous being Andrei Tarkovsky’s loose adaptation of Roadside Picnic in Stalker (1979), along with other works such as The Dead Mountaineers’ Hotel (1979), The Sorcerers (1982), Days of Eclipse (1989), Hard to Be a God (1989), The Temptation of B. (1991), the two-part Inhabited Island (2008) and its sequel Inhabited Island: Rebellion (2009), and Hard to Be a God (2013).

Trailer here

Full film available here