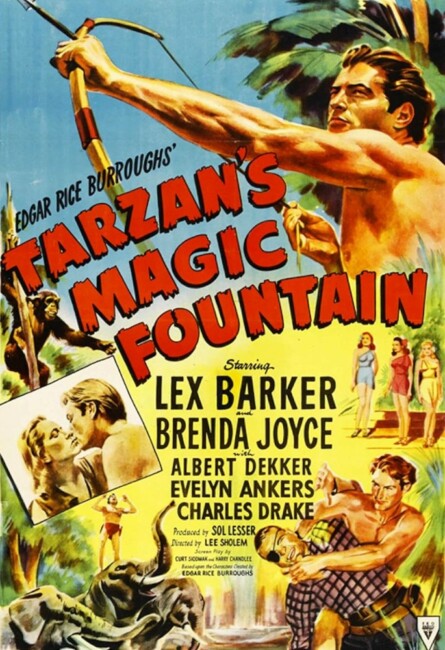

USA. 1949.

Crew

Director – Lee Sholem, Screenplay – Harry Chandlee & Curt Siodmak, Producer – Sol Lesser, Photography (b&w) – Karl Struss, Music – Alexander Laszlo, Makeup – Norbert Miles, Production Design – Phil Paradise. Production Company – RKO Radio Pictures/Sol Lesser Productions, Inc.

Cast

Lex Barker (Tarzan), Brenda Joyce (Jane), Albert Dekker (Trask), Evelyn Ankers (Gloria James), Charles Drake (Dodd), Alan Napier (Douglas Jessup)

Plot

Jane is surprised when Cheeta finds a notebook and it turns out to be from Gloria James, a famous flier who went missing in 1928. Jane thinks they should return it to civilisation to prove what happened to Gloria but Tarzan is reluctant to do so. He eventually takes the notebook to the outpost at Nyaga. He learns from the trader Trask that an innocent man is being accused of Gloria’s murder back in England. Tarzan then goes and brings Gloria back from where she is alive in the hidden Blue Valley. Both Jane and Trask are amazed that Gloria looks only in her twenties when she should be in her fifties. Trask sends men to find the Blue Valley and the secrets of its fountain of youth. Tribesmen from the valley come seeking to kill Tarzan because they suspect him of having leaked the secret of the valley’s location that he had promised to keep. Gloria returns from England sometime later, having married the accused Douglas Jessup but now looks in her fifties. She wants Tarzan to take her back to the Blue Valley so that she and Douglas can bathe in its fountain of youth and become young again. However, Trask and his associate Dodd are determined to force them to reveal the secret of the fountain.

Tarzan’s Magic Fountain was the thirteenth Tarzan film – at least in the series that originally began with Johnny Weissmuller in Tarzan the Ape Man (1932). Calling the Tarzan film a series is somewhat of a misnomer as a through line is erratic, given that the series changed its studio (from MGM to RKO Radio Pictures), changed its leading lady and (as here) changed its leading man.

RKO had steadily been putting Johnny Weissmuller through one Tarzan film a year for most of the 1940s but with Tarzan and the Mermaids (1948) he announced that he was quitting the part. RKO immediately set about finding a replacement. The actor chosen was Lex Barker. Unlike almost any other actor who had played Tarzan up to that point, Barker’s background actually was as an actor (on stage and in small screen parts) rather than as an athlete. Barker had played college football and served in the US Army during World War II but was in fact from a wealthy New York society family (who disowned him after choosing to become an actor).

Lex Barker would appear in a total of five Tarzan films for RKO beginning with Tarzan’s Magic Fountain here and followed by Tarzan and the Slave Girl (1950), Tarzan’s Peril (1951),Tarzan’s Savage Fury (1952) and Tarzan and the She-Devil (1953). Barker found difficulty finding work after leaving the role but did develop a new career in Europe, in particular in German krimi films, even playing a former Tarzan actor in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960).

Though the series has a new actor, Tarzan’s Magic Fountain emerges as the same formulaic Tarzan film as the preceding ten or so Weissmuller sequels. Held over is Brenda Joyce who had become Maureen O’Sullivan’s successor as Jane in Tarzan and the Amazons (1945) and stayed through the last three Johnny Weissmuller films. (She would be replaced in the next Lex Barker film). The character of Boy was written out of continuity from the second-to-last Weissmuller film Tarzan and the Huntress (1947) and would be forgotten thereafter.

The creaky formula of the series still churns through the same plot elements – lost jungle civilisations that promise death to all interlopers except Tarzan; greedy white men abducting Jane to lead them to a treasure. Just as much as ever, the film is given over to comedy relief antics with Cheeta – within the first two minutes of the film, we get scenes with Cheeta discovering the notebook and fooling around in the crashed plane and there are extended set-pieces throughout with Cheeta discovering blowing bubble-gum and playing with pepper as Tarzan puts on a barbecue. (There is one mildly amusing gag at the very end where Cheeta drinks some of the water from the Fountain of Youth and is reduced to a baby chimp).

Johnny Weissmuller was never a particular great actor but at least imprinted the role of Tarzan as something definitive. Even though he comes from more of an acting background than Weissmuller did, Lex Barker seems much more blank in the role. For one, he comes with too much of a handsomely sculpted bearing to be someone you could credibly believe as being raised in the jungle. Johnny Weissmuller imbued the part with a petulant, childlike innocence but there seems none of that in Barker’s performance.

The plot device of a fountain of youth marks one of the few occasions when the Tarzan series introduced overtly fantastical elements. Aside from the basic premise of a man being raised among the apes (where the Weissmuller series was notable for avoiding any depiction of Tarzan’s origin), the Tarzan films seems remarkably resistant to incorporating any of the regular fantastical elements to be found in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan books. This can perhaps be put down to the employment on script of Curt Siodmak, a hack writer and science-fiction novelist who was best known for writing the original The Wolf Man (1941), several of Universal’s Frankenstein and Invisible Man sequels from the early 1940s and the thrice-filmed novel Donovan’s Brain (1942). Siodmak has stolen much of the basic plot here from the hit Columbia film Lost Horizon (1937), which concerned a mythical Himalayan valley where travellers who end up there find a life of enormous longevity away from the stresses of civilisation. That perhaps thrown together with the public fascination over flier Amelia Earhart who disappeared during a flight in 1937.

Even so, the development of the fountain of youth and lost valley elements are dealt with in unsatisfying ways. The film skips from Tarzan learning that an innocent man is on trial for Gloria’s disappearance and passes through his travelling to the valley and appealing to get her back in about two minutes. We never even get to meet Gloria until she is brought back to the treehut. The script skips over any explanation of why she is in the valley and why Tarzan is covering up her disappearance, leaving us with a good many questions for much of the film. There is also no direct explanation of her rejuvenation, only speculation by others as to what happened until her return to Africa later in the piece.

The film seems to be doing everything it can to avoid tackling the idea of a Fountain of Youth. Indeed, about the only thing the film can think that such a fountain would be used for is when the two greedy white men make the sexist assumption that they could make their fortune by selling it to women because they are obsessed with looking young. Mostly, it feels like the film has filched the basic idea of Lost Horizon and grafted onto it the usual formula of the Tarzan film about greedy white explorers seeking treasure and superstitious natives trying to kill Tarzan. Most of the film is taken up with these formula pieces of plotting rather than spent in the Blue Valley.

Tarzan’s Magic Fountain was the directorial debut of Lee Sholem (1913-2000) who became a prolific tv director throughout the 1950s and 60s. Sholem also made the succeeding Barker film Tarzan and the Slave Girl (1950). He subsequently directed Johnny Weissmuller in two of his non-Tarzan jungle adventure films Jungle Man-Eaters (1954) and Cannibal Attack (1954). Sholem also made several other B genre films with Superman and the Mole-Men (1951), the film that became the basis for the George Reeves tv series Adventures of Superman (1952-8); the robot film Tobor the Great (1954); the mummy film The Pharaoh’s Curse (1957); and the sf film Doomsday Machine (1972).