UK. 2002.

Crew

Director – Danny Boyle, Screenplay – Alex Garland, Producer – Andrew MacDonald, Photography – Anthony Dod Mantle, Music – John Murphy, Music Supervisor – Sallie Jaye, Visual Effects – clear, Digital Effects Supervisor – Tony Lawrence, Special Effects Supervisors – Richard Conway & Rob Hollow, Makeup Effects – Creature Effects (Supervisors – Alan Hedgcock & Cliff Wallace), Production Design – Mark Tildesley. Production Company – DNA Films/The Film Council.

Cast

Cillian Murphy (Jim), Naomie Harris (Selena), Brendan Gleeson (Frank), Christopher Eccleston (Major Henry West), Megan Burns (Hannah), Noah Huntley (Mark), Stuart McQuarrie (Sergeant Farrell), Leo Bill (Private Jones), Ricci Harnett (Corporal Mitchell), Marvin Campbell (Mailer)

Plot

A group of animal activists break into a research laboratory and, despite warnings, free a group of monkeys infected with the deadly virus Rage. 28 days later, Jim, a bicycle courier, comes out of a coma after being run down, only to find the hospital and the rest of London deserted. Out in the streets, he is pursued by maddened red-eyed zombies but is saved by two people, Selena and Mark. From them he learns that all civilised order has collapsed after the entire country was overrun by Rage infectees who transfer the disease via their bite. After Mark becomes infected and has to be killed, Jim and Selena find two other survivors, Frank and his young teenage daughter Hannah. Frank picks up a radio broadcast from a military unit in a blockaded compound in Manchester and they decide to travel there. However, once accepted inside the compound, Jim is faced with having to protect the two girls from the group of all-male soldiers who are going crazy out of desire for women.

28 Days Later is a low-budget British horror film that ended up becoming a surprise international hit. 28 Days Later went out into British release in late 2002 where it did only modest business. It then gained considerable word of mouth after appearing at the 2003 Sundance Festival and several other film festivals around the world. Fox Searchlight Pictures picked it up for release in the US in June 2003 where it surprised everybody by earning well over $45 million in gross. [Perhaps people went in mistakenly expecting it was a sequel to the Sandra Bullock AA comedy 28 Days (2000)?]

28 Days Later was certainly a return to form for director Danny Boyle. Danny Boyle first appeared with the fine thriller Shallow Grave (1995) and then had a worldwide sensation with the cultish Trainspotting (1996). However, at the same time that he started to be courted as a major new talent, Boyle also started to lose the plot for a time. A Life Less Ordinary (1997), an eccentric kidnap comedy with angels, had its moments, but was generally regarded as unsatisfactory, while his major studio-backed feature The Beach (2000) was just plain dreadful. His next films, the black comedy Vacuuming Completely Nude in Paradise (2001) and Strumpet (2001), while both attaining good word-of-mouth, were barely released outside of film festival screenings.

For 28 Days Later, as with both Vacuuming Completely Nude and Strumpet, Boyle has made a determined effort to strip the filmmaking process back to basics. The film was made on a relative shoestring – as Hollywood budgets go – of $8 million. Moreover, Boyle cast unknowns in the leads, using only two moderately known British faces – Christopher Eccleston and Brendan Gleeson – throughout. The film was shot on digital video, something that allowed much greater versatility in camera and lighting set-ups in the difficult shoot in and around London. Boyle has employed cameraman Anthony Dod Mantle, a British cinematographer who has spent much time in Lars von Trier’s camp, shooting a number of Dogme films. Boyle also works from a script by novelist Alex Garland – a considerable surprise considering the mess that Boyle made of Garland’s novel with The Beach, which was possibly one of the worst botch-ups of an eminently filmable book conducted in recent memory.

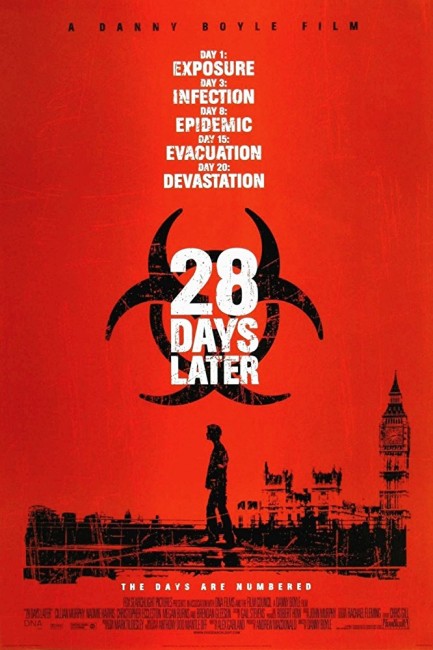

The poster for 28 Days Later calls the film “genre-busting horror.” The problem is that is exactly what 28 Days Later is not. Instead of a film that lays a genre open and redefines it, 28 Days Later is more one that stirs a familiar stew of elements. It is constantly reminding one of other works within the downfall of civilisation/post-holocaust genres. The survivors wandering the ruins after the world has been decimated by plague is a well-worn theme from works like George R. Stewart’s classic novel Earth Abides (1949), the late, great British tv series Survivors (1975-7) and Stephen King’s The Stand (1977); the lone survivors fending off hordes of infected reminds of Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954), filmed as The Last Man on Earth (1964), The Omega Man (1971) and I Am Legend (2007), or George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978); and the harsh brutality of survival theme has been conducted in films like Panic in Year Zero! (1962), No Blade of Grass (1970) and The Ultimate Warrior (1975).

The two works that 28 Days Later sources the most blatantly are John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids (1951), filmed as The Day of the Triffids (1962), The Day of the Triffids (tv, 1981) and The Day of the Triffids (tv, 2009), and George Romero’s Day of the Dead (1985). The opening of the film with Cillian Murphy waking up in the hospital and discovering that during the time he has been out the whole world has been destroyed could have been virtually photocopied from the beginning of The Day of the Triffids. Even more blatantly the second half of the film – the scenes with the civilians entering into a military enclave; the women being sexually harassed by the soldiers; and particularly the zombie kept chained up for experimental purposes – has been virtually copied scene for scene from Day of the Dead.

It is hard to decide whether to look upon 28 Days Later as being a homage to a particular genre (the post-holocaust and the zombie film) or merely a regurgitation of its plot devices. It is a debate as to what Alex Garland and Danny Boyle’s intentions were, but ultimately one feels like 28 Days Later is a film that invests too little in the way of original ideas into the material that it reuses to stand as a redefining or “genre-busting” work. Certainly, it is a modestly effective film, hardly a standout within the genre, but passably well made. However, on a wider sense it fails to always connect. There is little explanation offered of the disease and why it turns people into infected zombies – the notion of a disease that can cause an entire metabolic change within the space of ten seconds is medically ludicrous. The end of the film buys into the wish fulfilment notion that underlies many of these survivalist films of an almost miraculous restoration of the status quo, but this is so generic that we never even learn where the fighter plane that flies over comes from.

Danny Boyle also fails to do anything particularly original with the imagery of the genre. He does a commendable job of portraying a picture of a ruined London during the opening scenes with Cillian Murphy walking past numerous landmarks strewn with debris and overturned buses and of vistas out across an entirely deserted London by dawnrise or with the lights out. The scale of what one is seeing becomes all the more impressive when one reads about the logistical problems that Danny Boyle and his crew had in shooting, where they were limited to only being able to hold up traffic for several minutes at a time or filming during the early hours of the morning when no people were on the street.

Outside of that, the depiction of the downfall of civilisation is standard. Danny Boyle offers up cliché images of the survivors raiding supermarkets and symbolically leaving useless credit cards behind to pay for everything – while amusing, you cannot help but think of the far more socially potent images of the survivors walking through an empty shopping mall in Dawn of the Dead. There are occasional images – the moment Boyle pulls back from Brendan Gleeson explaining about how he is trying to trap rainfall water on his roof to show an entire rooftop covered in buckets; or the survivors looking at the glorious freedom represented by horses roaming wild in a field. However, there is nothing in 28 Days Later that ever resonates with the poetry of isolation and madness that came in the first half of The Quiet Earth (1985); with the satiric social commentary of survivors trying to cling to materialism that we saw in Dawn of the Dead; or the bleakness and the logic of ordinary people trying to rebuild everything from scratch in tv’s Survivors.

The zombie scenes are shot in fast edits that make the action seemed blurred and hard to follow. (This also has the dubious advantage of keeping most of the gore only briefly glimpsed). Danny Boyle does a decent job of sustaining suspense, particularly during a hair-raising scene in an underground tunnel where the four try to change a tire on the taxi as the zombies close in. Surprisingly though, this is the only scene where Danny Boyle pits his heroes up against the zombies and puts the screws on the audience – contrast that with the constant life and death struggle that came in Dawn of the Dead.

Danny Boyle is at his best in getting some decent characterisations out of his cast. Cillian Murphy seems somewhat blank and passive as a hero – he rarely does much throughout and when he turns into an action man, single-handedly taking on a troupe of soldiers in bare chest, it is a change-about that feels unconvincing. (That said, 28 Days Later ended up launching Cillian Murphy’s name on the international stage). Much better up against him is Naomie Harris, who projects an inner toughness and an often-wry wit that brings a strong drive to the centre of the film. The interplay between Cillian Murphy and she, mostly she, grants a resonance that forms an effective, if occasionally slight, backdrop to everything. Christopher Eccleston also gives considerable sympathy to a role that in another actor’s hands might merely have been one-dimensional villainy. Brendan Gleeson, usually cast as tougher-than-nails Irishmen, gives a performance of great strength and vulnerability as an ordinary man, while young Megan Burns is also fine as his daughter.

28 Days Later is a film that has the dubious benefit of a multiplicity of endings. In fact, there are two of them in the current cinematic release viewed here. One is the happy optimistic ending following the escape from the military enclave, which suddenly blows up into 35mm and shows the survivors now living in a cottage, ending with the fly-over of the plane and the promise of deliverance. However, in the midst of the film’s US release, Danny Boyle announced that he was not happy with this upbeat ending and tacked on another ending and cheekily re-released the film as 29 Days Later. Now if one waits all the way to the very end of the credits there is a considerably more downbeat alternate ending entitled ‘but what if?’ where Cillian Murphy is rushed to hospital after the crash through the gates and expires following attempts to revive him. The benefit of two such endings is dubious. The DVD releases contain a number of alternate scenes that never made it to the final print, as well as the storyboarded version of a further ending that was later abandoned as being implausible, which had the group discovering a cure for the disease after reaching the military blockade.

28 Weeks Later (2007) was a sequel that was much superior in all regards. The upcoming 28 Years Later (2025) is a further sequel.

Danny Boyle and Alex Garland next collaborated on the hard science sf film Sunshine (2007). Boyle went onto the award-winning hit of Slumdog Millionaire (2008) and the survival film 127 Hours (2010), the mind-bending hypnotism thriller Trance (2013) and the biopic Steve Jobs (2015), as well as returned to genre material with a theatrically live broadcast stage adaptation of Frankenstein (2011) and the alternate history Yesterday (2019). Alex Garland went onto write the script for Sunshine, the excellent science-fiction film Never Let Me Go (2010), the comic-book adaptation Dredd (2012), before making his directorial debut with the excellent artificial intelligence film Ex Machina (2015), which was followed by Annihilation (2018), the extraordinary tv mini-series Devs (2020), the folk horror/gender politics film Men (2022) and the near future Civil War (2024). He has also been associated with the long-announced remake of Logan’s Run (1976) and Peter Jackson produced film based on the Halo videogame.

(Nominee for Best Supporting Actor (Brendan Gleeson) at this site’s Best of 2002 Awards).

Trailer here