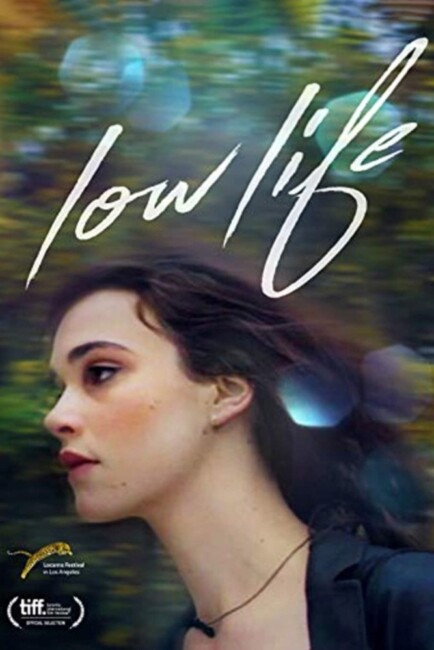

(Les Amants de Low Life)

Crew

Director – Nicolas Klotz, Screenplay – Nicolas Klotz & Elisabeth Percival, Producers – Alain Guesnier & Gilles Sandoz, Photography – Helene Louvart, Music – Ulysse Klotz & Romain Turzi, Special Effects Supervisor – Christophe Schmitz, Production Design – Antoine Platteau. Production Company – Agora Films/Maia Cinema/Les Films du Losange/Rhone-Alpes Cinema/Canal +/Cine +.

Cast

Camille Rutherford (Carmen Alvarez), Arash Naimian (Hussain Khodra), Luc Chessel (Charles), Michael Evans (Djamel), Maud Wyler (Julie)

Plot

A group of young people are involved in a communal lifestyle, where they party, debate politics and philosophy and engage in protests. Charles loves Carmen but she instead becomes interested in Hussain, an Afghan refugee who is studying in France. They begin a passionate love affair. At the same time, a document is being passed around that kills whoever receives it. Hussain then receives news that his appeal for asylum has been rejected and an order for his deportation issued. He and Carmen decide that they do not want to part and he moves in with her. There they become increasingly more fearful and paranoid about surveillance and the threat of arrest by the authorities.

Low Life is a French film that is doing the rounds of the film festivals. I found it a frustratingly opaque film that at over two hours of running time tired one’s patience. It takes a long time clueing you in as to where it is going. The first three-quarters of an hour seem to consist of a portrait of a group of student radicals that lead a communal lifestyle of sorts. Much of the time is spent featuring various of the characters and their associates falling in and out of love, discussing philosophy and politics, as well as their becoming involved in protests against the police. In this respect, Low Life feels like a typical French film of the 1960s – it could easily be a work directed by Jean-Luc Godard or Robert Bresson in their heyday.

During the first hour or so, these scenes are interspersed with a baffling B plot where it appears that Arash Naimian has had a voodoo doctor conduct a ceremony to place a curse on his deportation papers that, in a plot borrowed from Night of the Demon/Curse of the Demon (1957), causes anybody who receives them to be killed. There is also a subplot about the artist Julio that Arash Naimian flats with who develops an inexplicable malaise and just lies on his bed staring into the distance. In neither case is there any clear explanation of why things are happening – they have the effect of being bafflingly random plots that are unrelated to much else in the film. In particular, the voodoo curse plot feels like it belongs in a horror film rather than an otherwise realist work about student politics that is attempting to critically tackle the big issue of France’s policy on immigration and asylum seeking. Much of this also appears to take place in a non-linear fashion where the cursed immigration papers seem to be killing people even before Arash Naimian receives them, although this is never made clear.

After nearly an hour or so, Low Life does eventually key us in to what it is about. It is the story of how Camille Rutherford and Arash Naimian fall in love and make the decision that they do not want to be parted after he receives notice from immigration authorities that his application for asylum has been rejected and that he must leave the country immediately. This leads to a bleak existence where the two of them spend all their time inside their room never going out out of fear that he will be arrested. In the final scenes, Camille Rutherford is summoned to the police station where, after much apprehension, she finds it is about another matter altogether, but uses the opportunity to deliver a denouncement of the cruelty of the immigration laws and the cctv surveillance society.

This does bring me to the big bugbear that I have with Low Life – and that is that it is, just like Steven Spielberg’s The Terminal (2004), a film about immigration problems that seems to not know much about the reality of what it is talking. Now, I have to codify my comments here – things could well be different in France than it has been in my own immigration experiences. Nor have I ever sought asylum, however I do have considerable familiarity with immigration procedures in several countries. The Terminal was a fantasy of immigration in exactly the opposite way to Low Life – it regarded US Customs and INS authorities, in reality one of the most draconian immigration regimes in the world, as essentially good, decent people. In any real world US setting, Tom Hanks would not have been given the freedom to wander around the airport but have been kept locked up in an immigration holding facility for several years.

Low Life is a fantasy that goes to the opposite extreme of The Terminal. It seems to imagine that becoming an overstayer in a country automatically makes one akin to a Jew under the Nazi regime hiding in people’s attics fearful that the authorities may have the house under surveillance or burst in the door at any moment – even that to simply go out on the street is to invite instant arrest. In reality, what would happen is that Arash Naimian would be given his deportation papers – or more likely offered the choice to leave the country of his own volition – and afterwards perhaps authorities would come around to his listed address to see if he has left. (Most countries surprisingly have no procedure in place to monitor if someone leaves a country or not). If it were found that he had failed to exit the country when ordered, he would be listed as a fugitive and an arrest warrant issued. End of story.

The reality is that people live years, sometimes decades, on expired visas – even in the USA where there is an entire black currency based on illegal and overstayed immigrant labour. Authorities do not have the resources and manpower to track down or closely monitor the homes of every overstayer, let alone their friends – it is simply not a high-enough priority for them. The only real time that Arash Naimian would be in danger of being apprehended would be if he did something that drew him to the attention of authorities – such as commit a crime or try to pass through one of the police checkpoints we see where he would be required to show id.

The other question that gets me is if Camille Rutherford and Arash Naimian could not bear to be parted then why did they simply did not go and get married? This should be more than enough to supersede his deportation. It would no doubt be accused of being a marriage of convenience but from the closeness of the relationship we see on the screen, there should be little problem convincing people of the authenticity of their relationship.