Crew

Director – Francois Truffaut, Screenplay – Francois Truffaut & Jean-Louis Richard, Additional Dialogue – David Rudkin & Helen Scott, Based on the Novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953) by Ray Bradbury, Producer – Lewis M. Allen, Photography – Nicolas Roeg, Music – Bernard Hermann, Special Effects – Bowie Films & Charles Staffel, Production Design – Syd Cain. Production Company – Enterprise Vineyards.

Cast

Oskar Werner (Montag), Julie Christie (Linda Montag/Clarisse), Cyril Cusack (Captain), Anton Diffring (Fabian), Jeremy Spenser (Leader of the Book People), Bee Duffell (Book Woman)

Plot

In the future, books have been outlawed as reading is thought to only lead to idealism, which brings dissent, unrest and unhappiness. A special police force known as Firemen locate and burn caches of illegal books. Montag is one such Fireman. He has no reason to doubt what he does until Clarisse, the schoolteacher who lives next door to him, asks him if he ever reads any of the books he burns. His curiosity piqued, Montag steals a book on his next call and starts to read it in secrecy. Firemen raid Clarisse’s house but she escapes and tells Montag of a colony of people devoted to keeping books alive by memorizing them. Montag goes to quit but the Fire Chief persuades him to come on one last job, which turns out to be his own house. However, Montag turns his flame-thrower on the Firemen and becomes a fugitive.

Fahrenheit 451 comes from Francois Truffaut (1932-83), one of the leading luminaries of the French New Wave of the 1960s. Truffaut had made acclaimed films such as The 400 Blows (1959) and Jules and Jim (1962) and would go onto the likes of the Hitchcock-influenced The Bride Wore Black (1967), The Wild Child (1969), Day for Night (1973) and The Story of Adele H. (1975).

With Fahrenheit 451, Francois Truffaut turned to the work of science-fiction writer Ray Bradbury. Ray Bradbury had become one of the great mainstream crossover successes of the 1950s, writing classics such as The Martian Chronicles (1950), Fahrenheit 451 (1953), Dandelion Wine (1957) and short story collections such as Dark Carnival (1947), The Illustrated Man (1951) and The Golden Apples of the Sun (1953). (See below for Ray Bradbury’s other screen adaptations).

Ray Bradbury’s work evokes a melancholic nostalgia for lost American childhoods and comes with a sentimentalised idealism that extols simple-mindedness and tradition and distrusts change and technology. Francois Truffaut, by comparison, was one of the more soberly intellectual of the directors to emerge out of the New Wave, an ironist rather than a sentimentalist. Truffaut had originally wanted to film stories from The Illustrated Man but decided instead to adapt Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953). Apart from the very loose adaptation of Bradbury’s short story The Foghorn (1951) into a single image in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), Fahrenheit 451 was the first time one of Ray Bradbury’s works had been adapted to the screen.

Much has been debated about whether the film does Ray Bradbury’s book justice. With all due respect, Truffaut was never dealing a book that seemed that credible in the first place. Bradbury never sketched out how his society could have come into existence. For instance, you wonder why this society spends so much time burning books – wouldn’t the easiest way to stop people reading be to cultivate illiteracy? The art of reading is a learned one where people actively have to expend time learning how to interpret the symbols that make up letters and words and how they correspond to sounds – for the people of this future society to be able to engage in the forbidden act of reading, there must have been some society-wide mechanism to teach them to read in the first place. You ask other questions like – how does this society keep records, for instance? We see a scene where the police are tipped off by receiving someone’s photo in lieu of a name – but how is more complex data such as bank records and official information like birth certificates kept? In the film, Francois Truffaut never embellishes the world and leaves it a colourless milieu that lives in a vacuum. One can perhaps argue that Fahrenheit 451 is a cautionary story, so it does not need to be realistic.

Certainly, the film adaptation makes the story far more ambiguous than Ray Bradbury ever did in the book. The book ends with a nuclear holocaust taking place, leaving the Book People as civilisation’s hope for the future. The film drops the nuclear holocaust, leaving that hope only a faint one. Ray Bradbury regards the issue of book-burning and the loss of imagination and literacy by the society of the future as one of idealistic outrage. [In later years, Ray Bradbury insistently spoke out against interpreting Fahrenheit 451 as a novel against government censorship and states that he intended the book as being about how television presents a death of the imagination and kills off the art of reading].

By contrast, Francois Truffaut makes the case less black-and-white. He makes the point when he moves into closeup on the books that are going onto the bonfire, which include not just the literary classics but also copies of Mein Kampf, De Sade and Nietzsche. It is a point that obliquely criticises Ray Bradbury’s blanket worship and commemoration of all literature irrespective of what.

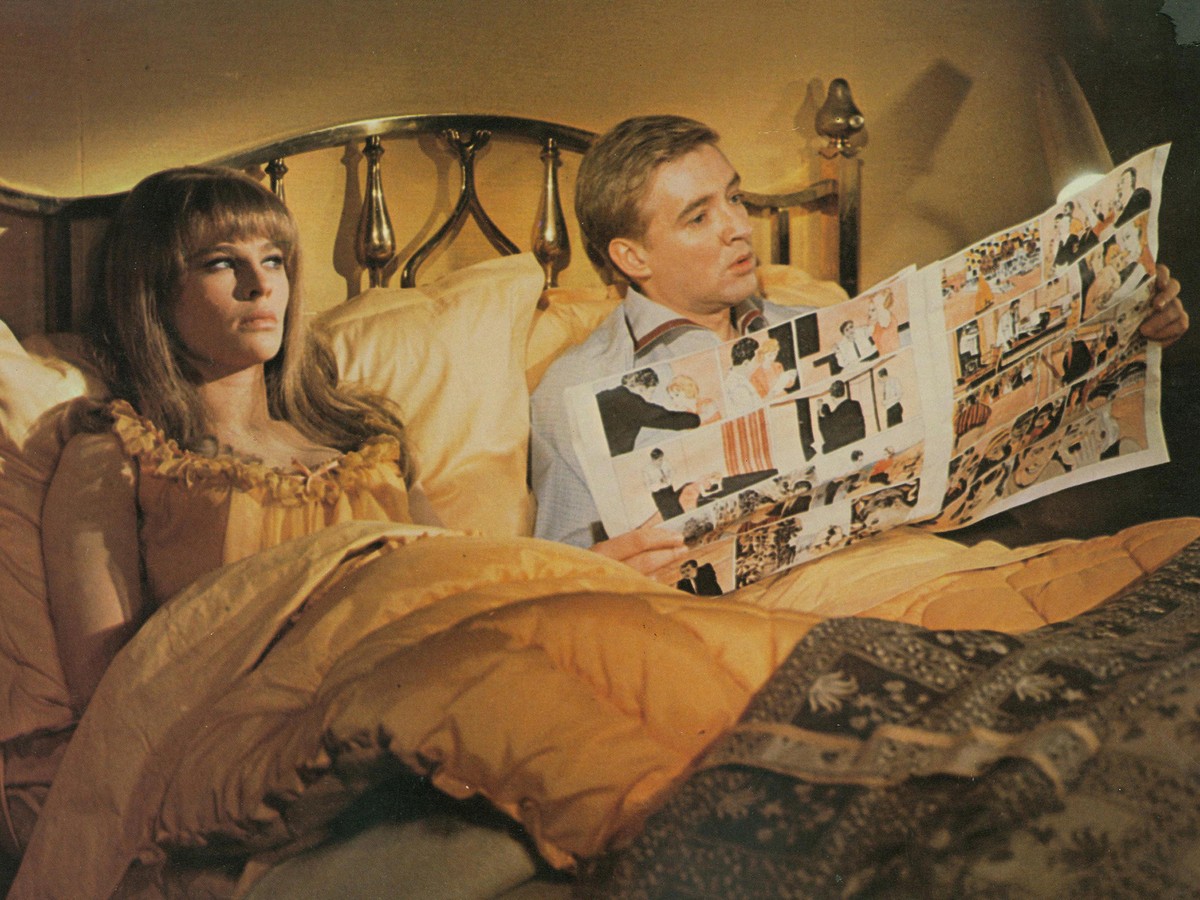

Ray Bradbury was in all likelihood inspired by the book-burnings that went on under the Nazis and his work is ‘lit up’ by the outrage at the loss of literacy and imagination that such a world might hold. For Francois Truffaut however, Fahrenheit 451 is less about taking a stand in a totalitarian future than it is one about rebelling against a cloying middle-class lifestyle. We get the sense that what causes Oskar Werner to become a revolutionary and start reading books is not intellectual curiosity but a desire to find imaginative life in contrast to the numbness of the pill-popping, soap opera-addicted world of his housewife. Truffaut has both Oskar Werner’s wife and the revolutionary schoolteacher played by the same actress Julie Christie, which serves to symbolise that the two women in Werner’s life are mirror opposites – the wife represents a banal, narcotised middle-class existence; the schoolteacher represents intellectual vibrancy and life. When Montag takes up the books and starts reading, it is a challenge to his bourgeois values – Truffaut improvises a scene over Ray Bradbury where Oskar Werner brings out one of his books and starts defiantly reading it in front of his wife’s middle class tea parties, and the ending where Werner torches his own house contains a perverse pleasure on Truffaut’s part in the way he drinks in the torching of the bedroom and lounge in sensuous detail, for what it is is the joyous incineration of an entire way of life.

Dramatically and in terms of characters, the film comes out hesitantly. Oskar Werner, who speaks with a thick (Austrian) accent, makes a singularly boring hero. The romance between he and Julie Christie’s equally underdeveloped schoolteacher never gets fired up. A sense of satirical humour in the scenes with Julie Christie as the wife and the participatory tv soap opera or the two blasé medical technicians come to pump Christie’s stomach after a suicide attempt lurks without clearly emerging.

Where the film does make up for this is in the bold alacrity with which Francois Truffaut tackles the visuals. There is a marvellous opening scene on a book raid that is conducted in a series of precise dramatic shots with the red fire engine buzzing through the countryside, the Firemen breaking into the house and burning the books, all accompanied by Bernard Herrmann’s stirring score. It sets the scene for the film perfectly.

Truffaut is interested in the flames the Firemen light just as much the dialectic of ideals and the film is filled with wonderfully colourful, often beautiful images – Bee Duffell’s decision to throw herself on the bonfire of her books; one charming silent vignette where Oskar Werner and Julie Christie watch a man unsure whether to make a tip-off or not; and the pretty ending, which often moves people as much as it causes them to laugh, as the Book People wander amid the snowy trees reciting books to themselves. On camera, Truffaut has Nicolas Roeg, later to become an acclaimed director – see the genre likes of Don’t Look Now (1973) and The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) – who makes some wonderfully exciting contrasts of bold, primary colour. Hitchcock’s composer Bernard Herrmann contributes an immensely exciting score.

Fahrenheit 451 was Francois Truffaut’s only ever venture into genre cinema. His one other genre credit of note was his performance as the UFO expert in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Truffaut’s film The Wild Child (1969), with its true-life story of a child that lived in the wild, has had some minor influence on the genre, most notably as a realist contrast to the ape-man myth of Tarzan.

In the 1990s and 2000s, both Mel Gibson and Frank Darabont expressed interest in directing a remake of Fahrenheit 451. This finally emerged with the appallingly bad HBO movie Fahrenheit 451 (2018) starring Michael B. Jordan as Montag, which substantially rewrote the book.

Other Ray Bradbury screen adaptations are:– the aforementioned The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) from his short story The Foghorn; the alien invader classic It Came from Outer Space (1953) from his original screenplay; The Illustrated Man (1969) from his short story collection; the dreary tv mini-series The Martian Chronicles (1980) based on his classic book; the tv movie The Electric Grandmother (1980); the screenplay for the fine Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) from his own novel; a Russian-made Bradbury anthology The Veldt (1987); his screenplay for the animated adaptation of the classic comic-strip Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989); the tv anthology series The Ray Bradbury Theater (1986-92) where he adapted his own stories and hosted the series; the screenplay for the animated children’s film The Halloween Tree (1993); Stuart Gordon’s adaptation of The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit (1998) about a seemingly magical suit; A Sound of Thunder (2005) based on Bradbury’s classic time travel story; Chrysalis (2008) where a man mutates into another lifeform; and the tv movie remake of Fahrenheit 451 (2018).

Trailer here